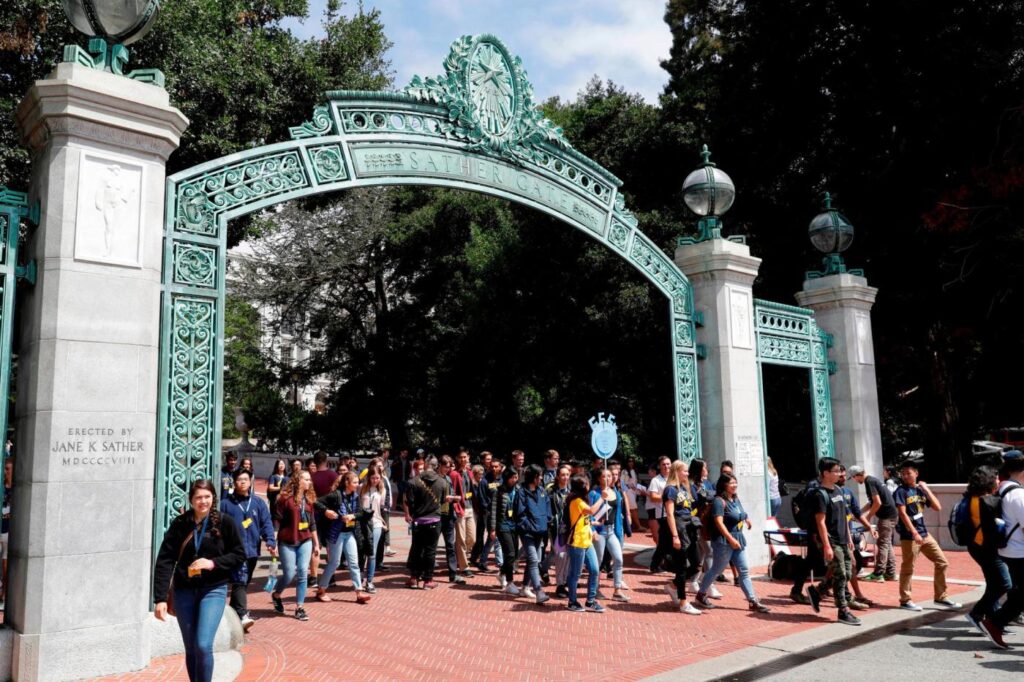

The city of Berkeley’s supposedly progressive residents are using NIMBYism to wage war on young people and their economic freedom. A small group of Berkeley residents has sued to stop the university from expanding. Thanks to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), the California supreme court upheld a judge’s ruling that has frozen enrollment until an exhaustive environmental impact report is completed. The decision will compromise the admission and education of thousands of students.

This absurd turn of events shows a fundamental bias at work, not just in CEQA, but in California more broadly: the belief that growth is inherently destructive and that it should be stifled to protect the status quo. We need to embrace CEQA reform as a first step in rejecting this anti-growth mindset before CEQA destroys our state.

CEQA has become a ubiquitous tool for neighborhood residents to block development of all types because it will negatively impact the community. The Berkeley residents argue new student housing will impact the community in the form of more traffic and noise, less parking, and in some cases, less green space. All of these are real environmental side-effects of new housing, and they are worth taking seriously and trying to mitigate when possible. The problem is that CEQA fails to balance the costs with the enormous environmental benefits of new development. Building new housing in our cities is one of our most effective tools to reduce traffic, improve air quality, and de-carbonize our economy across the whole state.

Urban development empowers residents to live, work and recreate closer together. CEQA often harms the environment because it privileges the desire to avoid trivial local environmental impacts over the desire to prevent catastrophic changes on a much higher level. Infill development that replaces residential, commercial, or parking with new housing is a net benefit to the environment.

Worse yet, there is no attempt to quantify the benefits of new development on economic opportunity for economically disadvantaged residents. Along with many other University of California universities, UC Berkeley is a remarkably efficient engine for economic mobility. Research shows that out of all “elite” American public universities, UC Berkeley is the fifth-best at promoting overall economic mobility and the fourth most likely to see its poorest students become well-off adults. It would be political malpractice to deny thousands of students the opportunity to raise themselves up just because a few residents think it would be inconvenient.

The passage of CEQA in 1970 marked a symbolic turn in California’s politics. Up to that point, California was arguably the most pro-growth state in America. California was synonymous with a hopeful vision of migrating to find economic mobility in the ample supply of new housing, jobs in booming industries, and a state-of-the-art public university system for young adults. Of course, this vision had substantial blind spots. Cities like Berkeley have a long history of denying the majority of its African Americans and Mexican American residents full access to the best neighborhoods, jobs, and colleges. As Darrell Ownes pointed out, Berkeley was one of the cities that most aggressively used zoning and housing covenants to exclude African Americans.

But rather than embracing inclusive growth, post-1970 California has instead adopted scarcity, a mindset that research shows fundamentally undermines inclusion and economic opportunity. Nowhere is this more clearly visible than in the housing market. Despite persistent demand for Californian homes, the state largely stopped building housing around 1970. In 1960, Los Angeles had a population of 2.5 Million but enough zoning capacity to accommodate 10 million people. In 2020, the population had grown to 4 million, but zoning capacity had shrunk to accommodate only 4.3 million people. This scarcity has priced economic outliers out of the market. As a result, California now has a housing market where only the affluent can stay. At the same time, thousands of residents leave the state, exporting our housing problems to cities like Spokane, Washington, and Bozeman, Montana.

We need to revitalize California by embracing a new paradigm: an economy premised once again on embracing the growth that seeks to benefit residents of all backgrounds. Taking a cue from Atlantic writer Derek Thompson, this agenda would fundamentally embrace creating economic abundance rather than coping with scarcity. We need a policy agenda that makes it possible for an abundance of housing to be built, along with the jobs, infrastructure, and green energy required for a modern economy. It would also seek an abundance of people, welcoming immigrants from all places and making it easier to participate in this growth.

Since all of these goals are held back by CEQA, the first step in committing to this new paradigm is simple: reform CEQA to exempt infill development. Of course, this reform alone will not end our scarcity mindset, but just like its passage served as a symbol of the start of a darker era, its reform can serve as the start of a new age, one where abundance is achievable for all.

Thomas Irwin works for a faith-based non-profit in Los Angeles focused on economic development. He is also a member of the Southern California Association of Government’s Housing Leadership Academy, and helped start Elevate Equity, a program for under-resourced entrepreneurs. He lives in East Los Angeles with his wife and son.