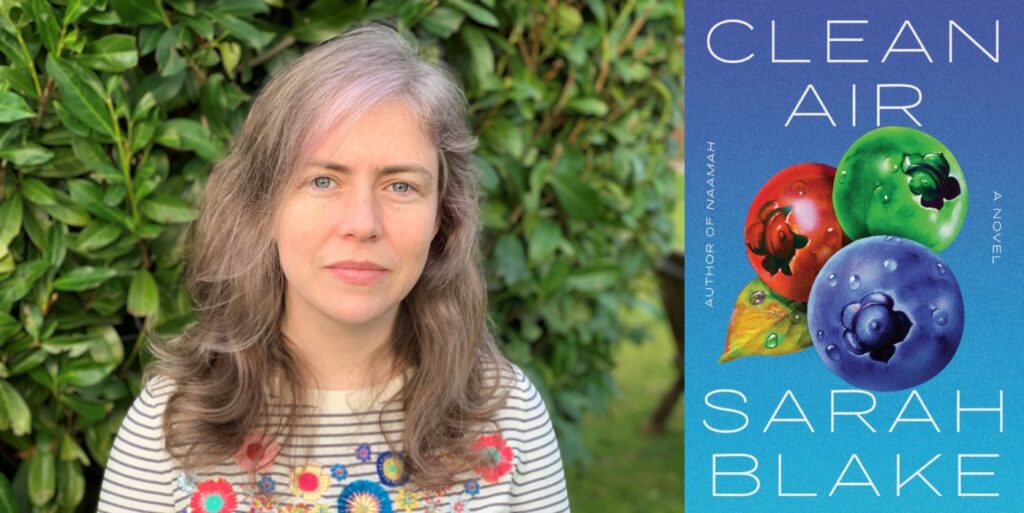

Sarah Blake’s “Clean Air” offers plenty for readers: It’s a dystopic novel set in the near future, a decade after The Turning – where tree pollen turns deadly and kills off vast swaths of the population, forcing everyone else to live inside or to wear protective masks outdoors.

But it’s also a utopic novel, where society has been rebuilt in a safer and more equitable way… until all that is threatened by a serial killer rampaging through a town, slashing the protective exteriors of homes, killing off entire families.

And while much of the book is a novel about mother nature, it’s also a novel about the nature of mothers and daughters. Izabel is still grieving the loss of her mother, who died just before The Turning, while raising her precocious daughter, Cami… and feeling like the rest of her life is devoid of meaning. Then Cami, who views the trees outside car windows as her friends, starts having strange, possibly supernatural dreams and Izabel gets drawn into the serial killer’s orbit, endangering her family’s safety.

Related: Get more stories about books, authors and best-sellers with the free Book Pages newsletter

The book’s premise may seem otherworldly but much of it, from emotional details to anecdotes, came from the real life of poet and novelist Blake, whose previous work of fiction, “Naamah” reimagined the story of Noah’s Ark from the perspective of Noah’s wife.

“The ties are really strong to me,” Blake said in a recent video interview. “I was writing about my grandfather’s death 15 years ago but then my mother died and I was working on the revisions having just been through that kind of loss.”

But just as with her book, not everything is bleak. “The book was partly inspired by my son who had a tree friend at the bus stop when he was five,” she says. “Every day he had to say hello and goodbye and hug his tree friend.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q. You wrote about a catastrophic event that kills people off and alters society, creating a world in which no one can go outside without a mask on. But you started three years before the pandemic.

People have been writing to me about the timeliness. It was really bizarre. I had friends in California who, because of the wildfires, had kids who had to wear masks to go to school. There are so many different ways the air can be not clean.

Also, my allergies were getting really bad and there were a good three years where I kept ending up in the ER because my asthma would get so out of control. It could take a good six months till my breathing got back to normal.

Q. So pollen was a real danger for you.

Willows are my worst.

The reactions really wipe me out. It’s better in the UK for some reason. When people say how unrealistic this is in the book, I say, “Well, just watch me.”

I drew on my reactions quite a bit for how they experienced going out in the air; I’m a cougher, which is very frustrating because it’s hard to communicate.

Q. How much of this book derives from your own fears about the climate crisis and environmental degradation?

I go through waves of that. I remember seeing firsthand the devastation of Hurricane Sandy. To watch it was something. I recycle and don’t even own a car. But you realize it’s up to the corporations at this point – the big differences would have to come from there, so you have to be okay with the loss of control.

I started to get involved with local politics and working on newsletters about issues like fracking. Some of the ones Izabel reads online are ones I’d done. There’s always something new to get terrified about and in “Clean Air” I was trying to write about all the disasters I’m concerned with.

Q. In terms of environmental damage, do you think we will only change our ways after something as dramatic and destructive as The Turning?

For a change that really made the world astonishingly better, then yes. Instead, I think we’ll find ways to survive through crappiness for a very long time, making small changes so people can have the sense that they’re living a normal life even when one normal is quickly surpassing another.

Q. You write literary novels that tackle serious issues but you seem to love building alternate worlds.

I am a sci-fi kid at heart. My dad always had “Star Trek: The Next Generation” on, so world-building has always been fascinating for me. I continue watching and reading sci-fi but I ended up on the literary side. There are not many poets like me who write sci-fi poetry.

This book lived in my head for a while once the world popped into my mind. I had a lot of it done before I even started writing. It’s such an enjoyable part for me. My next book is a completely made-up world though it is closest to contemporary time.

Q. And then you work a serial killer crime thriller into all this. Where did that come from?

I love procedurals and murder mysteries. They’re my outlet. I’m re-watching “Elementary” with Lucy Liu and I think they do a really good job with characters. The genre is huge; I find my niches. As a teenager, I’d fall asleep to “Law & Order.” I’ve watched probably every “Law and Order” up to season 18. And “Law and Order: SVU” helped me deal with some of my deep-seated fears about rape – they were talking about it on that show in surprising, direct and honest ways that really were helpful.

After I built the world, I started with Izabel writing letters to Cami; and once I developed that mother-daughter relationship and started to understand who I was spending time with, I sat down to write and the first thing that came out was this trip to the hospital and that there was a serial killer.

Part of what makes writing fun for me is my main character is usually stuck in some way that can feel hopeless. It’s usually based on times in my life – some times for years at a time – where I felt very stuck and hopeless, whether it be within in the confines of a marriage or being far from my mother while she was dying or living in a country where the government was failing.

So I thought what can I gift Izabel, who feels totally adrift and purposeless – The Turning hit when she was at the age where she would have been finding herself and building her identity and she got locked down instead with those choices gone. It’s weird but I gifted her a serial killer. It got her unstuck, bizarrely enough.

Q. For a dystopic novel, your characters live pretty comfortably. Given the dysfunction in our society already, wouldn’t things go far worse if we had something like “The Turning,” something closer to Cormac McCarthy’s “The Road”?

I think honestly people would just die. I’m not optimistic about human nature, but I did want to write a book that was.

The kernel of all of this was that I did not want to read “The Road,” I thought it would be too much. Then I had to read it to teach it when I was a long-term substitute. I wasn’t wrong. It wrecked me.

I wondered if there’s a way to have the dystopic but to have the other side. I knew if you couldn’t even go outside you couldn’t scavenge and couldn’t riot. I went above and beyond with the utopic aspect.

I want people to have an enjoyable reading experience. I‘ve had enough grief in my life the last few years, so I wanted to do something that isn’t just going to make you cry for ten pages. Joy is what I’m writing toward.

Related links

Why Kim Fu says ‘Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century’ is meant to be strange

Naomi Hirahara talks with author Joe Ide about updating Philip Marlowe in ‘The Goodbye Coast’

How anime fuels Tochi Onyebuchi’s ‘Goliath,’ a sci-fi novel about those left behind

In ‘Devil House,’ John Darnielle blurs true crime with blood-soaked fiction

The Book Pages: The free bookstore field trip you need to know about