The U.S. Supreme Court announced Monday, Feb. 28, it will hear oral arguments in a case challenging a 44-year-old law that gives preference to placing American Indian children in state foster care with American Indian adoptive families.

A ruling could determine the fate of the Indian Child Welfare Act, which has withstood challenge since its implementation in 1978. The law provides guidance to states regarding the handling of child abuse and neglect as well as adoption cases involving American Indian children, setting minimum standards for the handling of such cases.

Supporters of the act maintain it has helped stem a centuries-old practice by the federal government and private agencies of systemically separating American Indian families. Opponents brand it as a race-based law that gives preferential treatment in adoption proceedings to American Indians.

“As leaders of our respective tribes, we know the importance of keeping our children connected with their families, communities and heritage,” said a joint statement released Monday by the leaders of the Morongo Band of Mission Indians in Cabazon, the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin and the Quinault Indian Nation in Washington state.

“ICWA has proven itself as the gold standard of child welfare law, which is why both Republican and Democratic administrations, tribes and tribal organizations, and child welfare experts continue to defend it.”

In September 2021, the tribes joined U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, who is of American Indian descent, in petitioning the nation’s highest court to uphold the ICWA after efforts by a white Fort Worth, Texas, couple to adopt Cherokee-Navajo siblings were thwarted by social workers who opted to place the children with American Indian families.

Lawsuit origins

In the the fall of 2017, Chad and Jennifer Brackeen, the couple trying to adopt the children, joined the state attorneys general in Texas, Indiana and Louisiana in filing a federal lawsuit testing ICWA’s constitutionality. A federal judge in Forth Worth declared the act unconstitutional in October 2018.

The case then ping-ponged its way through the federal appellate court system until April 2021, when the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans overturned the Fort Worth judge’s 2018 ruling.

The Fifth Circuit’s voluminous opinion, at more than 300 pages, was a mixed bag that largely upheld the Indian Child Welfare Act. However, some judges agreed that certain provisions of the act were unconstitutional, leaving the outcome murky.

So the plaintiffs and defendants petitioned the Supreme Court to clear it up.

Roadblocks

While the Brackeens were successful in state court in their efforts to adopt a Navajo-Cherokee boy, they hit another roadblock when they tried to adopt the boy’s half-sister, who was placed with a tribal family in Texas.

“This case is about preserving the Brackeens’ family and, especially, the continued well-being of the little girl that they are seeking to adopt, who has thrived as part of the Brackeens’ family now for more than two years,” said family attorney Matthew D. McGill in an email Monday. “We are pleased that the Court has chosen to review all of the important constitutional issues raised by the parties.”

Texas maintains that ICWA is a race-based system that creates a “child-custody regime for Indian children defined by a child’s genetics and ancestry,” and is designed to make the adoption of American Indian children by non-American Indians more difficult.

Texas Solicitor General Judd E. Stone II, who is representing Texas in the case, did not respond to emails Monday requesting comment.

Turning point

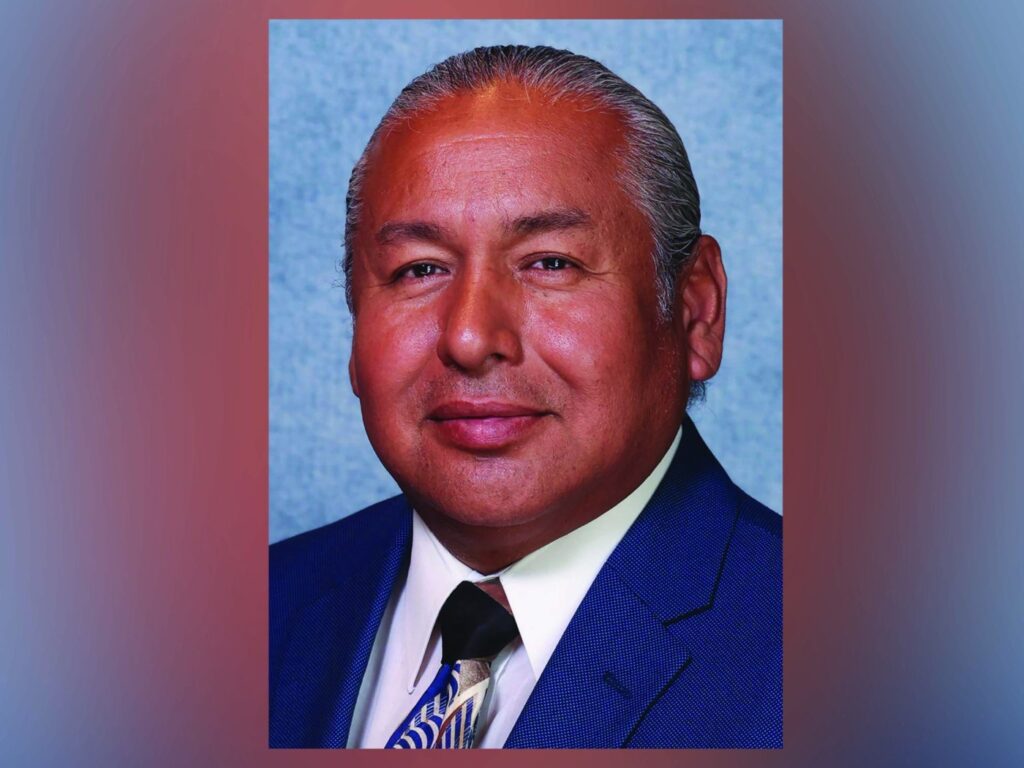

In a statement Monday, San Manuel tribal Chairman Ken Ramirez said ICWA’s enactment marked a significant turning point for tribes in protecting their citizens by maintaining a child’s connection to their family, culture, and community. He said that before the law was imposed, American Indian children faced forcible removal from their families without full consideration of their political status and cultural identity.

“We hope the United States Supreme Court will affirm the constitutionality of this critical law that protects the rights of Indigenous children and tribes here in the U.S.,” Ramirez said.

Anthony Morales, chairman of the Gabrieleno San Gabriel Band of Mission Indians, could not be reached for comment.

Never return

In their joint statement Monday, the four tribal leaders said, “We are confident that the Court will come down on the side of children, families and centuries of legal and constitutional precedent.”

Morongo tribal Chairman Charles Martin said in a statement Monday that the pending Supreme Court decision to consider key provisions in ICWA will “provide tribes the opportunity to correct a wrongful ruling by the Fifth Circuit.”

“I am confident that the Supreme Court will fully uphold ICWA, as courts have repeatedly done for over four decades,” he said.

Threat of extinction

Assemblyman James Ramos, D-Highland, a San Manuel Indian and former chairman of the tribe, in February introduced two pieces of proposed legislation, one to recruit and support homes for American Indian foster youth and another toimprove county compliance with state and federal child welfare laws.

“It is always hard to educate the community about the cultural aspects of Native Americans,” Ramos said in a statement Monday. “The very real threat of extinction caused by genocide and forced assimilation have resulted in tribes taking strong actions to protect the identity and culture of our children.”

By retaining a strong cultural identity to their roots, American Indian children — already stricken by separation from family members — better endure the challenges and traumas of family separation, Ramos said.

“Tribal foster youth do not always have the same protections as other foster children, and often little effort is made to find appropriate tribal placements,” Ramos said. “Ensuring more collaboration and communication between the various legal jurisdictions and equitable and adequate resources for tribal foster kids in the court and educational systems are critical factors in creating a process that works for children.”