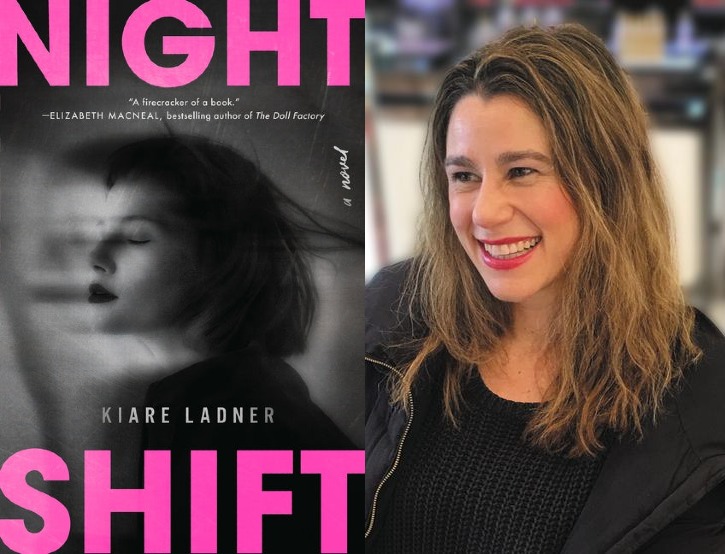

In the early pages of Kiare Ladner’s debut novel, “Nightshift,” 23-year-old Meggie is a bit of a wallflower, a good girl with a boring job and a nice boyfriend who mostly represses her urges and accepts her lot.

Then a new co-worker named Sabine arrives radiating style, sensuality, mystery and, well, life. Meggie feels a strong desire to be Sabine’s friend – or even more; ultimately, she realizes she wants to transform herself into Sabine.

Desperately trying to keep the enigmatic and elusive Sabine close, Meggie follows her to a new job clipping articles, working an overnight shift for two weeks followed by two weeks off. The schedule and the slippery Sabine wreak havoc with Meggie’s equilibrium and her life starts spinning in new, sometimes dangerous directions. Lander’s propulsive pace mimics Meggie’s frantic emotional state; in the heat of her obsession with Sabine, Meggie pushes her own limits, trying to discover who she really is.

Related: Want more stories about books, authors and best-sellers? Get the free Book Pages newsletter

Like Meggie, Ladner came to London from South Africa in the 1990s (when the book is largely set). Unlike her intense characters, however, Ladner has an easy smile and is quick to laugh. In a recent video, Ladner discussed what working nights felt like to her and why it was important for Meggie to be able to upend her life without being judged.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q. You’ve said Sabine “feels to me like someone I know incredibly well.” But she’s an enigma to Meggie and us. Did you get to know her much better than Meggie did and then obscure her from Meggie and us?

The book is fiction. I’ve never had a Sabine, but I’ve had close relationships and friendships and obsessive ones. I was thinking a lot about female friendship — some I’ve had that seemed to burn and then die.

So I feel like I have a gut sense of Sabine but probably even now I couldn’t tell you what school she went to or which aspects of her life were true or not. It’s more about something elemental about the kind of person she is I can channel.

I have a great deal of feeling for that kind of person. I love a woman who is tough and vulnerable and out of place. I feel very protective of that kind of person. One can see aspects of that in yourself.

Q. Did you ever work a night shift?

I worked nights in the job that Meggie does. The experience of doing nights really imprinted itself on me. I was always trying to figure out ways to earn a living and write. My obsession was with writing. I found it fascinating. I regarded myself as a night owl before I did it. So I thought it would work brilliantly.

Your perception of time changes a lot. Like Meggie, I also couldn’t sleep in the day. I used sleeping pills the whole time and they screwed me up and I was in a haze. Also, I drank a lot. It was fun but I couldn’t ever get on top of it. And I was in a crazy relationship with a jazz musician who had their own crazy hours. Sometimes I was trying to live days and nights. It was an incredible experience, but for writing, I need a really clear brain and I didn’t have that.

Q. Did you draw on those fast-burning relationships or on the way you obsess about writing to capture Meggie’s compulsive behavior regarding Sabine?

Both. I’m quite an obsessive person in some ways so easy for me to tune in to that. Every week I have to do this enormous run because as long as I can do it, I can do it. But also I find it strange but fascinating to watch someone sleep. I’m not some creepy person but there’s just wonder in seeing another person’s existence. I can’t stop marveling over other people. I do sound like this alien from another planet when I say things like that.

Q. Meggie makes bad decisions, small and large, some of which actually endanger her well-being. But she is no longer being passive, she’s in control of her life, making those moves on her own even when she’s simply trying to be her own version of Sabine. How important was that sense of control to her?

She’s genuinely trying to explore herself and dare herself to go as far as she can go and to push at these boundaries. In the book’s darkest scene she originally had less agency but I changed it. She pushes to the point where she questions why is it important to respect yourself. That’s a divisive line with readers but to me it was really important – the book is about her not taking anything for granted, not even daylight. She’s not conforming to what we’re supposed to conform to, she is stripping all this B.S. we are told to want away and just ask, “What am I? What can I become?”

I’m interested in what happens when you want to be someone else – when your lived life doesn’t feel like it reflects who you are – you can accumulate a life of experiences and how that appears to other people can still leave you feeling there’s something that’s integral about you that’s unexpressed and the sum of the parts of your life doesn’t add up to the whole of you.

She pushes away her boyfriend and Earl who is a good guy but it’s not just about her rebellion – Earl doesn’t quite get that this is something she needs to do. She’s got to be very much on her own to lose herself, which she wants to do. Looking back she would not have regrets – she was vitally alive then.

Q. Was it important to you that Meggie does not suffer in the long term for her explorations and indulgences with drugs and sex, that she not be punished for it, even if friends disapprove?

I wanted to allow Meggie the freedom to go as deep and as far, to explore as much, as she needed.

I’m trying to get at the dominant narrative in society, the puritanical approach to these subjects, which I’m very much against. I find it incredible how stories with alcohol, drugs and, in particular, excess and risk, are supposed to align with conservative notions of self-care. There’s this bizarre disjuncture – where society allows us to blank the mounting risks of our behavior to the planet but encourages extreme risk aversion on a personal level.

It’s frustrating that this judgmental approach is still aimed more sharply at women than men. It particularly troubles me when as a writer you feel this subtle pressure for your story to conform to a certain message. In terms of excess and risk, there’s still a sense of the right story around these subjects being “what a consumer audience needs it to be.”

I think “Nightshift” will find its readers and someone who doesn’t get the book’s attitude won’t open their minds – I think maybe they’ll hate it. I wasn’t interested in writing a morality tale. That would have bored me. It would have hurt my soul.

Related links

Why Kim Fu says ‘Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century’ is meant to be strange

The incredible true story that inspired Kaitlyn Greenidge’s new Civil War-era novel ‘Libertie’

How novelist Jessamine Chan created the dystopian ‘School for Good Mothers’

How ‘The Golden Girls’ and a chance meeting led Maggie Rowe to ‘Easy Street’

Sign up for our free newsletter about books, authors, reading and more