After two investigations and months devising new rules and procedures to prevent another deadly training accident with its amphibious forces, the Marine Corps is now deciding whether six men in various command roles should keep their military careers.

The men each made decisions in the training and preparations for a 2020 deployment, including the planning and carrying out of a raid by a platoon of amphibious assault vehicles onto San Clemente Island. During the trip back to an awaiting Navy ship, one of the AAVs sank, killing eight Marines and a naval corpsman – the deadliest amphibious training accident in the service branch’s history.

Convened in a spare courtroom-like facility at Camp Pendleton – troops training near could be heard – Marine Corps lawyers made a case for why the men should be demoted or even removed from the military – these hearings are only about positions in the Corps, none of the Marines are facing charges. One board was held back east at Marine Corps Base Quantico.

Marine Corps investigators into the accident said the accident was preventable and military leadership have said the Corps has taken responsibility for lapses in safety procedures, the poor state of the vehicles used and holes in the men’s training – making a series of changes to prevent a reoccurrence, they said.

These recent boards spanned seven weeks, interrupted twice by COVID-19 delays.

In a few cases it appears the hearing boards have recommended the leadership and performance of the men directly involved be labeled “substandard” and at least one recommends a retirement. But the panels – made up of Marines of varying ranks from a staff sergeant to colonels – found no basis to go forward with a review of at least two lower-ranked Marines after listening to their and others testimonies.

Not all of the recommendations have been made public and the final decision lies with the commanding general of the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force, known as the boards’ convening authority. He is expected to review the preliminary recommendations and pass those along to the Secretary of the Navy. Final results could take months.

An impossible situation

In a life-and-death struggle, Cpl. Dallas Truxal gave his all to drive his sinking armored seafaring vehicle to the USS Somerset.

With surging waves whipping ocean water through the view hatch of his AAV, the now 24-year-old Marine was soaked from head to toe as he chased the Navy ship about three miles off San Clemente Island.

Bilge pumps that can empty out 440 gallons per minute, weren’t keeping up. Water was covering the deck plates – the point where training tells vehicle commanders to prepare their troops to get out of the 26-ton tracked vehicle that can travel on land and in water.

With 13 men from Bravo Company, Battalion Landing Team 1/4 inside its cramped compartment, the AAV left the island in a column of nine vehicles after completing the training raid – an exercise to prepare it to deploy with the 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit.

The exercise on July 30, 2020 was the first time the platoon trained in the water, and after 45 minutes of struggling to stay afloat, the AAV Truxal piloted was overwhelmed with water and sank, taking eight of the men with it. Another man was recovered nearby.

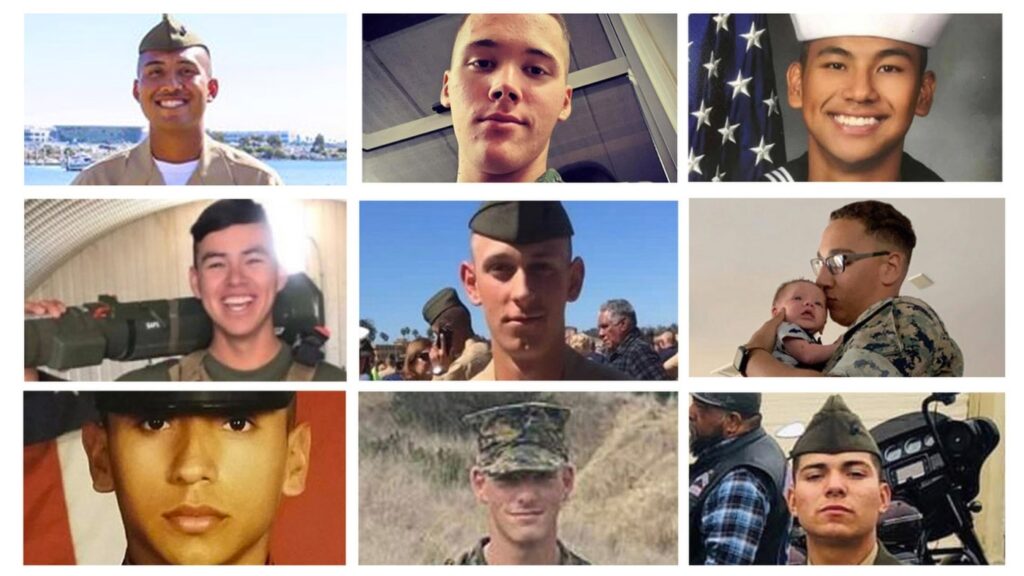

Three of the Marines came from Southern California – Pfc. Bryan Baltierra, 18, of Corona, Cpl. Cesar Villanueva, 21, of Riverside and Lance Cpl. Marco “Andy” Barranco, 21, of Montebello – and Navy Hospitalman Christopher “Bobby” Gnem, 22, a corpsman attached to the unit, was from Stockton.

A Marine Expeditionary Unit is supposed to be outfitted with the finest leaders, troops and equipment before it is deployed, when it is expected to be ready in six hours for combat or to provide humanitarian aid.

But this time, investigators say the fact that it was the first time the AAV platoon had trained in water, without some passing necessary swim qualifications or knowing how to escape a vehicle, speaks to the abbreviated training schedule as units were stretched between exercises, COVID impacts and other missions.

Col. Fridrik Fridriksson, who has commanded similar units, led one of the three investigations released since the accident. Following his eight-month review, he said “a confluence of human and mechanical failures caused the sinking of the AAV and contributed to a delayed rescue effort.”

“When the Marines didn’t realize how dire the circumstances were, it shows they weren’t trained well enough,” Fridriksson said in his testimony at the hearing boards. “Every single Marine and sailor (recovered on the ocean floor) had their gear on. They didn’t take the action they were supposed to.”

Testimonies in the last several weeks of hearings have been some of the first times families and the public have heard an accounting of the accident from the Marines who were there and who made decisions leading up to the day, providing new details into what happened, but also highlighting conflicting information and confusion swirling in the rush toward deployment.

The boards started at Camp Pendleton in early January with a review of Lt.Col. Michael Regner, who was Battalion Landing Team 1/4’s commander, which included this platoon, followed by Capt. George Hepler, the Bravo Co. commander at the time, 1st Lt. Thomas MacAleese, then the platoon commander, and two enlisted members, Staff Sgt. Herme Lacea, the platoon’s sergeant at the time, and this week Gunny Sgt. Trevor Johnson, who was in charge of the vehicle that sank.

A board for Lt. Col. Keith Brenize, the former commander of the 3rd Assault Amphibian Battalion that provided the “operationally inoperable” AAVs to the MEU concluded this month in Quantico.

Two other leaders in the chain of command were previously disciplined or relieved of duty.

THE G.O.A.T.

Truxal, who in January marked four years in the Corps, has been testifying in the hearings, telling members of the boards that his track (slang for an AAV) was the best “of our platoon for 90% of the workup.”

“She was the G.O.A.T. (greatest of all time),” he said. “She was good.”

The troop transport vehicle ran well during the island raid, he said, but, shortly before the “splash” back to the Somerset, the vehicle’s oil pressure dropped. The crew ended up scavenging oil from the other vehicles to get the AAV running again.

“We fixed the leak,” he said, ran it to make sure it worked and reported the issue.

Out at sea, the vehicle’s transmission would later seize.

“We had to keep chasing the boat because they kept landing helicopters,” Truxal said. “When I realized we were out further than we should be, we were closer to the ship than the shore so we kept chasing the boat.”

As Truxal pushed the vehicle forward, more and more water flooded in.

Chem lights previously attached were no long there on the AAV’s return trip to illuminate the hatches, so the Marines used cell phones – which they weren’t even supposed to have onboard – to find their way to the escape points. And, once there, they struggled to open the unfamiliar hatch against the pounding waves, investigators said.

Truxal told hearing board members that as the AAV finally sank less than a mile from the Somerset – it had been taking on water for 45 minutes – he swam from his seat through the vehicle grabbing two Marines on the way out of the hatch.

“If I didn’t know my way around that vehicle, myself and two other Marine’s names would be on that list – we’d be dead,” he said, adding that what helped him was that he swam competitively in high school. “I held my breath and on my way out I found two dudes pulled them out and crawled out of the vehicle and inflated my vest to go to the surface. Then I blacked out.”

Experienced Marines

Each of the Marine leaders before the boards was described as having stellar reputations, accomplished prior leadership and in some cases impressive combat experience. At each board, Marines called in to testify confirmed they would be willing to serve again with any of the Marines under review.

Several of the final recommendations, though not being officially released by the Marines, were discussed during the hearings by defense attorneys. In a statement, a 1st Marine Expeditionary Force spokesman said the preliminary recommendations are under review and would be released at a later date.

MacAleese was praised for his attention to safety, and, in a prior role, pushing to halt an amphibious exercise in Alaska when he realized the conditions were “too rough to splash.’”

“I don’t have a problem saying ‘no,’” MacAleese said. “If it’s not right, that’s cowboy-winging it and it’s not what we do.”

To make the SOPs easier to follow, he printed them out and laminated them for placement inside the AAVs.

His hearing board said they saw no basis for the allegations against the former platoon commander or to even consider if his actions fit the substandard or derelict categories. They are recommending he retains his position.

Lacea, the platoon’s staff sergeant who spent his entire Marine career in amphibious operations, was described as a subject-matter expert on safety and known as a “good Marine.”

His hearing board is also recommending he retains his position, saying there was no basis for his review.

Regner, son of a retired two-star general and a Citadel graduate, has led Marines in combat in Fallujah, Iraq and in the Helmand Province in Afghanistan. Regner is just about six months shy of his 20-year mark.

His hearing board is recommending, though they found him substandard in the performance of his duties in this instance, he should be retained.

Hepler, the former company commander, was described as very conscientious, detail-oriented and as a mission-focused Marine. He faces the same recommendation from his hearing board.

“I did my job the best I could with time and resources,” Hepler told the hearing board, adding his experience, even from a tragic accident like this, “makes me valuable to the institution.”

Brenize enlisted in the Marines in 1994 and then commissioned as an officer in 2000. He’s served in various roles as an assault amphibian officer and saw combat in Iraq and Afghanistan. His board convened at Quantico recommended retirement, an attorney said in one of the Camp Pendleton hearings.

Successes and training failures

Regner told his hearing board he was given a series of missions that distracted from preparations for deployment – even if his Marines excelled at the unexpected duties.

For example, a mission to secure 100 miles along the California and Arizona borders fell to his unit and his Marines were also sent “on a high-profile mission” to stand guard for the USNS Mercy, the Navy ship deployed at the height of the coronavirus pandemic to the Port of Los Angeles to help take patients from overburdened hospitals in the area.

Then the battalion had trouble getting pool access so the Marines could get the swim qualifications they needed to get out of a sinking vehicle – though they should have had priority because of the pending deployment, other groups got in the water ahead of the men and then a pool heater broke and an instructor had COVID-19.

Still, every company had time in the water, Hepler told a hearing board. “I didn’t believe they were improperly trained.

“The fact that every company had a day at the pool made me comfortable with the level of training they were getting and that it was consistent with other units. Had I known then what I know now, I would give anything to have had more time.

“Time was short.”

Still, Regner said the day before the raid to San Clemente Island, he made sure to alert others that the AAV platoon would be going in the water for the first time with their vehicles. “We wanted to make sure we had supervision,” he said. “As I looked around the room, most people nodded their heads, ‘I understand.’ Then it was, ‘Let’s go and do it.’”

He and Hepler both said they were assured by the Navy a safety boat would be with the AAVs – it had last minute mechanical problems and never launched. An AAV used by MacAleese as backup ended up with mechanical issues as well.

MacAleese also said his Marines trained to escape an AAV on land and then again on board the Somerset the night before the island raid. Truxal said he also gave the Marines a safety brief.

Also at question is whether the required pre-operation and pre-water checks were done before the AAVs left the Somerset and again on their way back from the island. They have to be signed off on before a vehicle is allowed to go into the water.

At least three Marines testified they were both done and logged for the platoon, including the AAV that sank.

“These checklists take a long time,” Fridriksson said in his testimony. “The first time you’re doing a launch with embarked Marines, you’d think checklists would be critical. But I didn’t receive a single checklist.”

When to get out

The AAV’s vehicle commander, Johnson, is facing criticism for not preparing his Marines to evacuate the AAV when the water reached the deck plates – that means get their weapons unslung and their gear off, including Kevlar vests – and for a lack of communication with others that his vehicle was in peril.

His board hearing wrapped up Thursday and the panel’s recommendations have not been discussed publicly.

“It’s difficult to judge him like an armchair quarterback,” MacAleese said of Johnson, who he put in place as a platoon section leader in charge of the AAV he rode in and three others, confident in his skills. “I think he thought he was protecting the Marines by keeping them in there, instead of putting them out in the water.”

The landing team’s most senior officer during the raid, Maj. Michael Jevons, who was in the column of AAVs along with the one that sank, testified in a phone call from Okinawa, Japan, that there was no indication from Johnson that sinking was imminent.

“We became aware the AAV was taking on water,” he said. “But the communication was not urgent – no one was asking for assistance. It seemed we were not in a moment of crisis.”

Then Johnson climbed on top of his troubled AAV waving a flag signaling distress.

“As soon as it was raised we moved to the AAV as close as we could,” Jevons said. “At that point, we still weren’t aware of the severity of the circumstance.”

Another closer AAV also moved in, but in the surging waves bumped the troubled vehicle, pushing the slowly sinking AAV sideways. A swell poured water through its hatch, knocking a couple Marines already out into the ocean and one back inside.

Within minutes the AAV had sunk.

Johnson, who testified during the final board on Thursday, also has a standout career in the Corps. He was meritoriously promoted as he moved up in his assignments, named Marine of the Year for the 3rd Regiment and amassed many awards as a recruiter.

He described how the ocean became rough after leaving the island’s cove, worse than the earlier trip. As the AAV traveled out, now the last in the column, his radio started to break up. That’s when he first waved the flag signaling distress, he said.

At the same time, he was trying to help Truxal steer toward the ship, he said. The waves were so high the driver’s hatch had to be closed and Johnson stood in the turret directing him “left, right, hit the gas, hold the gas, dodge this wave, now, right again.”

When the rear crewman pulled on Johnson’s leg to tell him the water was rising, Johnson said he was told the gauges were looking good.

Climbing out of the turret to take over driving to help Truxal, Johnson said, “Then I get another pull on my leg. I told (the rear crewman) not to panic and to prepare the Marines to evac. Truxal asks for help again and he said he heard a loud noise and water is coming in.”

Johnson was told the bilge pumps were still working, he said. “I thought we’re OK, we’ll make it to the ship.”

It was not until Johnson had another AAV near him that he said he made the call to evacuate the troops – water was nearly at the bench level.

“I didn’t evacuate because of the sea state, the power was on, the bilges were working and the fear of the waves coming over,” Johnson said. “If I had opened the hatches, I feared what eventually happened would happen.”

Capt. Jonathan Walther, the Marine defense attorney for Johnson, referred the hearing board to a 2019 AAV accident on the East Coast where the vehicle sank, but all the troops survived. In that case, which investigators said was appropriate, the vehicle commander also waited until the water level reached the bench before calling for an evacuation.

“He was considering that his Marines could drown, be hit by another AAV and that there was no safety boat,” Walther said of Johnson. “He was the rear AAV; all others were ahead of him. He knew he had to wait for the tracks. He had to wait until someone was there to get them.”

“The only difference between the 2019 and 2020 accidents is the result,” Walther said. “But the result does not define the decision.”

Related links

9 deaths in July’s Marine AAV training off San Clemente Island were preventable, investigation finds

Families look for closure in final report on deadly Marine AAV training accident

Marine Corps commanders ordered to make changes after deadly AAV training accident off San Clemente Island

Southern California Marine’s family wants more details on report about deadly AAV accident at sea

Families of Marines and sailor who died in AAV training accident are learning more about what happened

Two investigations underway to find cause of Marine Corps’ deadliest AAV training accident

3 Marines from Southern California among 8 service members presumed dead off San Clemente Island

Bodies of Marines and sailor recovered from the seafloor off San Clemente Island

Decorated Marine relieved of command after deadly sinking of assault vehicle off San Clemente Island

Community outpouring helping families of men who died in Marine training exercise

West Coast Marines are first to try out new Amphibious Combat Vehicle to replace legacy AAV

Reliving the pain

On some days, in the back of the room, behind the wives and families of the Marines being reviewed, sat parents of the men who died. They have addressed some of the hearing boards and submitted impact statements when allowed.

Lupita Garcia, of Montebello, said she had wanted to hear what led to the death of her son, Lance Cpl. Marco “Andy” Barranco.

“I always wanted to know,” she said. “I wanted someone to sit down, one-on-one with me, and tell me how it happened. At the same time, it’s just so painful.”

As details emerged during testimony, Aleta Bath, mother of Pfc. Evan Bath, 19, would quietly say, “No, that’s not right” to herself. Especially in one case, when Hepler testified the Marines had done their swim qualifications. She knew her son could barely swim.

On the cellphone she held on her lap, she pulled up a text exchange with her son on how his training was going.

“I’ve been praying for you,” she wrote. “I’m glad that you’re learning a lot. (Can they add swimming?)”

“That’s what the big metal tub in the ocean is for,” he responded.

Mom replied: “Until you have to jump out of that tub.”

“Marines don’t run from the fight, I’ll meet the water fist raised,” her son responded.

Bath, who lives in Wisconsin, has attended all but one of the hearings. First at Quantico and now at Camp Pendleton. She’s been away from home for seven weeks, all the while trying to stay on top of her job.

“I do not hate the Marines,” Bath told a hearing board. “To do so would be dishonoring my son’s legacy. He was proud to be a Marine. I am proud that he was a Marine. However, I am here to tell you, that I want all responsible parties held accountable, whoever they may be, and I want the culture of the Marines to change.”

Changes made

Since the accident and the investigations, the Marine Corps has made a series of changes that officials say will protect against lapses in procedures for amphibious operations and make sure an accident like this “will never happen again.” Training handbooks have been rewritten and new policies put in place; at more steps in the process leaders have to sign that things were properly completed.

In December, Gen. David Berger, the Marine Corps’ top leader, limited the Vietnam-era AAVs to land use only.

Replacing them are the Amphibious Combat Vehicle, and five months ago, when at least one toppled in the surf at Camp Pendleton during training, Berger quickly halted their use until faulty towing mechanisms were addressed.

In January, they were cleared for water use and participated in a training exercise at Camp Pendleton with the Japanese Ground Self Defense Force.

Two weeks ago, the ACVs for the first time did a ship-to-shore raid with the Navy.

And, during the training, the Navy had two safety boats in the water – a must now after the fatal AAV accident. The USS Anchorage also remained close by.

“The safety of our Marines and sailors is a top priority, especially as we continue to test the new capabilities of the newest Marine Corps platform,” Rear Adm. Wayne Baze said in a statement after the exercise.

In January, Berger signed off on an order requiring all Marines operating in water to pass the submerged vehicle trainer, showing they know how to get out. A colonel would have to sign off in a case where someone didn’t go through the training.

“No colonel is going to want to put his name on a document that says, ‘I’m accepting risk to send an untrained Marine through or over water,” said Retired Marine Col. Walt Yates, who spent years on training systems. “I think that will never be used or contemplated in my estimate.”

Jonathan Wong, who spent a decade in the Marines and is the associate director of the Strategy, Doctrine, and Resources Program at the Rand Research Organization, said he hopes the policy changes the Marines have made will stick.

He also commented that the preliminary results from the hearing boards don’t appear very decisive.

“Even though you have some accountability, particularly at higher places, it doesn’t feel like a concise commitment,” he said. But he’s known decisions to be overruled later.

“I do wonder what signal it sends to the rank and file,” he said.

Some parents of the men who died expressed disappointment over the recommendations they learned at the hearings.

“It feels like a punch in the stomach,” Bath said. “Did Evan even matter to them? They came into my home multiple times and told me that, in effect, the Marines killed my only child and here is a list of the people responsible. I then sat in board after board watching no one take responsibility, or be given responsibility.”

“It just feels like in the end there is next to zero accountability,” said Peter Vienna, father of Gnem, who both testified and submitted impact statements. “Only to see them get a slap on the wrist … that’s hard to take while grieving the loss of a child.”