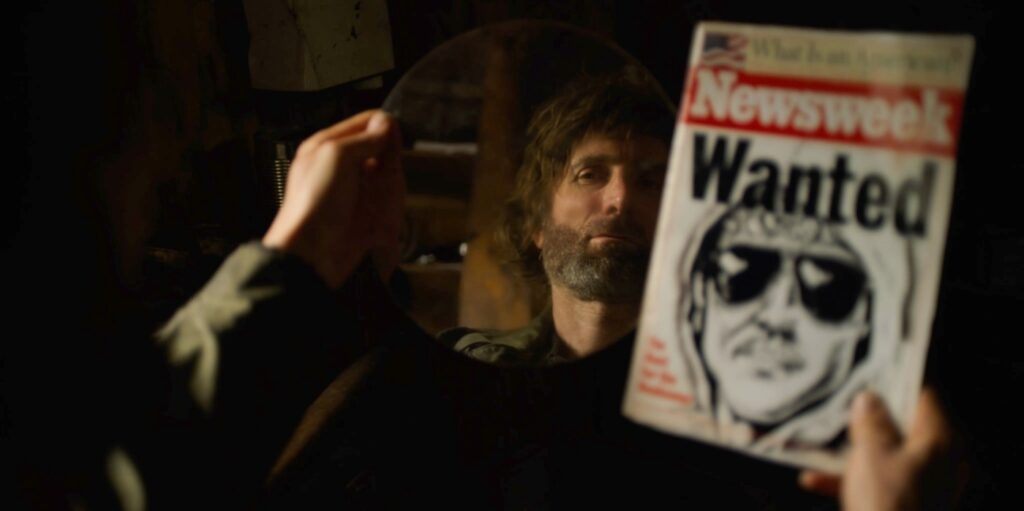

As a native of South Africa, actor Sharlto Copley says he had only a vague recollection of Ted Kaczynski when the opportunity to play the American domestic terrorist onscreen came his way.

“When they said, ‘It’s the Unabomber,’ I wasn’t sure which one he was,” Copley says. “I thought he was somebody who bombed a government building. They said, ‘No, the guy who was mailing bombs.’”

Then, over the course of auditioning and getting cast by writer-director Tony Stone to play the lead in “Ted K,” a strange thing happened, Copley says.

As he read Kaczynski’s voluminous writings, including the manifesto that led to his 1996 arrest, and watched interviews with him on YouTube, Copley says he found himself sometimes, uncomfortably, agreeing with him.

Not, Copley stresses, with the man’s violent methods, of course: Kaczynski’s bombs killed three and injured nearly two dozen. But the concerns about threats to the environment and the dangers of technology? Those weren’t that far removed from things Copley thought, too.

“The more I went into it the more I’m like, ‘Oh my God, this guy’s more right than I want him to be,’” says Copley, whose credits include the Neill Blomkamp sci-fi movies “District 9” and “Chappie.” “Like, I really don’t want to think that.”

“Ted K,” which opens Friday, Feb. 18, asks the viewer to consider those conflicting, often uncomfortable feelings thanks in large part to the fullness of the portrayal Copley and Stone bring to the screen.

“When you peel back the layers, it just becomes more and more interesting,” Stone says of the story, much of which was drawn from the 40,000 pages of journals discovered in Kaczynski’s tiny Montana cabin and conversations with people in the nearby town of Lincoln who knew the man, a former mathematics prodigy and professor who retreated from his academic career to live alone in the woods.

“We’re all still human, and it had become so black and white.”

Into the woods

Other film and TV projects have told the story of Ted Kaczynski but the filmmakers think none have achieved the verisimilitude of “Ted K.”

How authentic is the film? It was filmed in and around Lincoln, Montana, where Kaczynski settled in the woods in 1971, and some of the townspeople who knew him before his arrest appear onscreen.

Stone also built an exact replica of Kaczynski’s cabin, trucked it to his former property, and placed it on the foundation where the original once stood.

“It was so profound because it was on the exact spot where he was,” Copley says. “So things like every sound that I heard was like, ‘This is the sounds that he would hear right now. This is what he can see out of this tiny little window that he’s made.

“They even found a piece of the old stove and attached it to our stove,” he says. “It was haunting in a way.”

Stone says in the years of developing the project before he was ready to shoot he’d sometimes see Kaczynski’s old property listed for sale.

“I’d see the land, and be like, ‘Oh my goodness, I wish we had money and production could buy it,’” he says.

Then, when he was ready to go, his producer Matt Flanders, a Montana native, discovered his sister had gone to high school with the woman who owned the land. A call was placed, a connection made.

“It was just serendipity,” Stone says. “(Director) William Friedkin’s always talking about the film gods. There’s some truth to that. Like, how did I find Sharlto? How did I find the land?”

Gritty realism

While there are long, panoramic shots displaying the natural beauty of Montana that inspired Kaczynski when he settled there, the camera in “Ted K” is almost always on Copley as Kaczynski. Closeups ask the viewer to imagine what he’s thinking.

“I went reasonably method [actor], sort of staying in the voice and the character most of the time,” Copley says. “Tony had asked me, ‘Don’t shower or bathe the entire time,’ because he didn’t do that for massive stretches of time. I was like, ‘Oh, man, I’m just not sure.’ I like to be clean.”

He tried it, but only lasted two or three days, which became his pattern for the four trips the production made to Lincoln to capture footage in all four seasons.

“With movies, you can never be dirty enough,” Stone says. “So it was a lot of, ‘More dirt, more dirt,’ just to try to keep it as gritty as possible.”

Stone says locals were overwhelmingly open to the small production shooting in and around town. Some of the anecdotes they shared with Stone and Copley ended up in the film.

“I think people were excited that we were going to tell the Lincoln version,” says Stone, who had planned to hold the North American premiere in Lincoln before the pandemic hit and forced a move to Missoula.

“So much stuff has been made, and they don’t shoot there; they shoot in Georgia. And then it’s not the right library, and the scale, just everything is off,” he says.

Future echoes

For Stone, the exploration of domestic terrorism from abolitionist John Brown all the way to Kaczynski had long fascinated him, partly because of the stark divide between their motives and their methods.

“How would we think about Ted Kaczynski in 100 years when we’re really facing this climate catastrophe?” he says. “His heinous actions – or just look at his ideas?

“Environmental degradation has gotten worse, technology has become in control of us, and we’ve become a more polarized society,” Stone says. “Ted Kaczynski as a story has really started to become more interesting than it was even 10 years ago.”

Copley says friends all asked him if making the movie had been traumatic.

“I was like, ‘It was actually relaxing; coming back to my life is (bleeping) traumatizing,’” he says. “Like looking at my emails and all the stuff I’m supposed to do, that’s much more traumatizing than playing a guy who’s getting angry and shooting at the sky.”

In the months since finishing the film, Copley says the influence of Kaczynski’s world has nudged him toward nature over tech. At times, he’s surprised to find himself nostalgic for life before cell phones.

“How can I possibly miss when I didn’t have a phone?” he says. “The phone is so useful to me, isn’t it? But I really miss when I didn’t have a cell phone.

“You can talk to anyone now, whenever you want,” Copley says. “But still, something was more real about the life I lived.”

Related Articles

These three women are hosting the 2022 Oscars

‘Wayne’s World’ turns 30: Penelope Spheeris talks painful ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ scene in Covina

Tim Roth says he can’t wait to see ‘Sundown,’ his new film directed by Michel Franco