Author Tochi Onyebuchi is a self-described “member of the original Toonami generation” – meaning that in the late ‘90s and early ‘00s, he’d tune to Cartoon Network from 4-6 p.m. to watch a block of anime that included “Thundercats” and “Voltron,” and later on, “Dragon Ball Z,” “Sailor Moon” and “Mobile Suit Gundam Wing.”

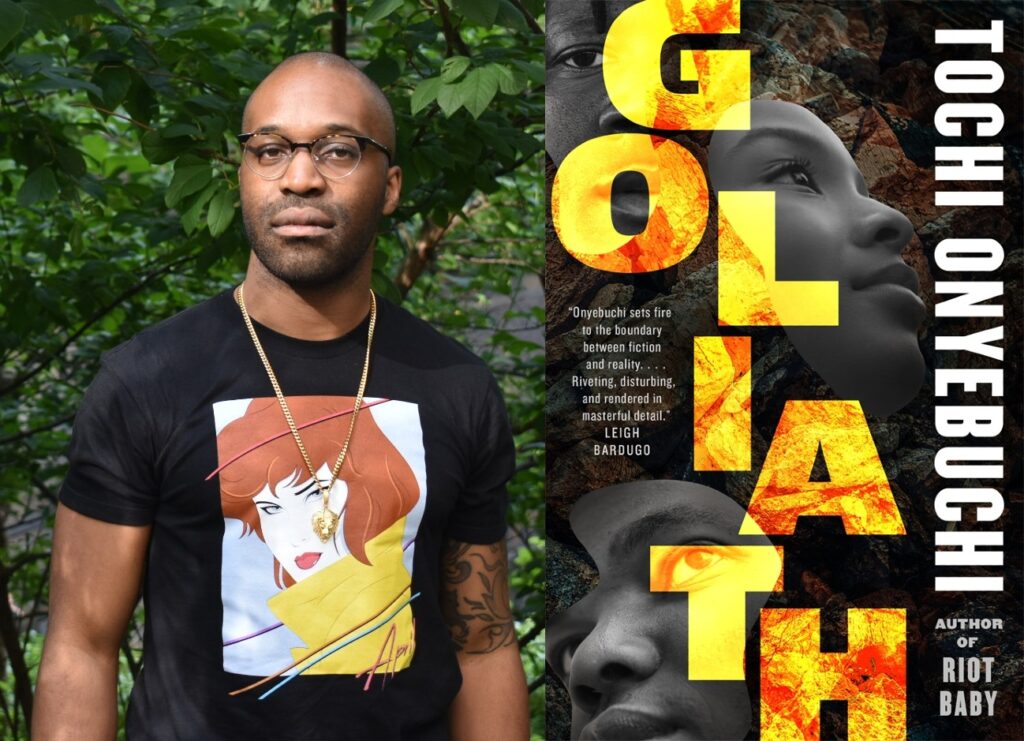

This programming block, which exposed a generation of American kids to Japanese animation, helped set him on his path to becoming a storyteller of speculative fiction, he says. The influence of anime is hard to miss in “Goliath,” Onyebuchi’s latest dystopian epic set in a future where the wealthy have fled Earth for space colonies, leaving those who cannot afford the journey to eke out lives on a planet ravaged by climate change. The book arrives in stores Jan. 25.

Related links

How ‘Murderbot Diaries’ author Martha Wells overcame a career in crisis to create the killer series

How novelist Jessamine Chan created the dystopian ‘School for Good Mothers’

How Neal Stephenson’s climate change epic ‘Termination Shock’ got its start at Burbank airport

Attorney and author Natashia Deón delves into LA’s troubled history with ‘The Perishing’

Sign up for our free newsletter about books, authors, reading and more

From summer to spring amid the crumbling remnants of New Haven, Connecticut, we follow the paths of various characters touched by this conflict. These include a construction worker tasked with tearing down houses for raw materials to be shipped to the colonies, a marshal transporting a prisoner, and a colonist who wants to return to Earth and build a life.

Through their stories, Onyebuchi explores what our future – despite the vast potential of space travel and colonization – might look like if the wealth, housing and racial inequities that we face in the here and now go unaddressed. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Q. I couldn’t help but see a lot of the anime series “Mobile Suit Gundam Wing” in this book. Can you talk about your anime influences?

I based the structure of the space colony on the colonies in “Gundam Wing”! It’s like a foundational text for me. A lot of my path through speculative fiction, through science fiction and fantastical storytelling, was guided by anime and manga.

I think two really salient points in my journey as a storyteller occurred in high school when I came across Hiroaki Samura’s “Blade of the Immortal” [manga series], which has now been collected in these gorgeous omnibus volumes. I have all of them, basically bearing down on a sinkhole of a bookshelf.

There was also Katsuhiro Otomo’s “Akira.” I remember seeing the movie back when the Syfy Channel used to do their Saturday anime block. It was so visually stunning. I came across the manga volumes in the public library and I devoured those 2,000-plus pages in about a week. I’d never seen a city fall out of the sky, but Katsuhiro Otomo gave me that.

“Gundam Wing” taught me just war theory. The main characters were child soldiers, worried about rebel movements and civil conflict all in a story about giant robots crashing into each other. That was very formative for me. Another one, “Fullmetal Alchemist,” is probably one of the greatest treatises on dealing with grief. So very early on, anime taught me that you can take something as simple as a fight scene and use it as a vessel for exploring incredibly mature and complex issues in a very real and multifaceted way. It’s been an influence on all of my storytelling.

Q. “Goliath” is coming out on the heels of the public’s discussion about billionaires in space and what that means for everyone else, especially with climate change. I thought that was a pretty interesting coincidence.

All speculative fiction, whether it’s millennia in the future or millennia in the past, is about our now. And that’s really all I’m writing about.

It’s funny, because the very first iteration of “Goliath” was written in the spring of 2015, and it was actually an outgrowth of a short story that I wrote in the summer of 2013. You can trace its origin all the way back to then. But things like having to wear masks, and rich people going off into space and leaving everybody else behind to deal with the effects of climate change – that’s an unhappy coincidence.

A similar thing happened with [Onyebuchi’s previous novel] “Riot Baby,” albeit on a more thematic level. I believe I sold the book in 2018, and then it was published in January of 2020. Just under six months later, George Floyd was killed. After that happened, people were suddenly turning to “Riot Baby” as a sort of book-of-the-moment, as though it was prescient in some ways.

But “Riot Baby” hadn’t been intended as a predictive tool – if anything, it was a commentary on the interminability of state violence towards Black Americans. I think a similar thing might be happening with “Goliath.” The idea that climate change will most adversely impact the least among us is something that’s been a reality since forever. So much of the book is already happening and has been happening.

Q. It feels like you did a lot of research around climate change and its impacts on things like physical and mental health, and how we reckon with it. Can you talk about that?

Absolutely. One of the joys for me about writing fiction, in general, is just the learning process. I’ve learned so much about climate change and its attendant issues, such as the idea of climate despair. That is, when you look at climate change as something so far outside of our ability to comprehend its dimensions – when you try to confront its enormity and the enormity of trying to keep it from destroying you and your livelihood? It can cause this existential despair. Why bother? Why are we even doing this? What can even be done? So it was interesting to come across that and to have to personally reckon with that.

On the flip side, it was fascinating to see all the different ways in which people coped with climate change – not just in terms of building sea walls, but sort of re-inventing their own relationship with the environment. How can I completely reconfigure my relationship with the environment such that we’re no longer antagonists?

So many of the issues attendant to climate change, at least how it has been and is and will manifest in the United States, we’re seeing on display now. Everything from the ways in which people are coping to how it impacts home insurance. The more research I did into places like Reserve, Louisiana [a predominantly Black community located close to petrochemical plants, where the risk of cancer is highest in the U.S.] – it’s actually called Cancer Alley — I feel like, particularly with speculative fiction, readers might come across something and assume that the author made it up. But they might be surprised by just how much of “Goliath” is happening now.

Q. There was a passage that stuck in my mind about terrestrial longing – this idea that colonists wanted to come back to Earth because of the immense history there. But the reality is that Earth is now a place that’s just “all history and no future.” Can you talk more about that?

That came from growing up in Connecticut. You’re constantly surrounded by things like the Wadsworth Museum, which is the oldest operating public art museum in the United States, and Mark Twain’s house, and this park that’s named after this person, and all this stuff that’s referencing revolutionary and pre-revolutionary times.

But you go to some of these cities, particularly a place like Hartford, Connecticut, and it’s like, What are the economic prospects of this place? People go there to make their money, and then they leave for the suburbs, and none of that money stays in Hartford to help build up local infrastructure and schools and things of that sort. There’s not really any sort of explosive art scene, it’s not an incubator for tech, or any of the things that could describe socio-economically dynamic places.

So I was like, “OK, what if the whole planet was that?” There’s hundreds of millennia of history on Earth. If we’re looking at space as a new frontier, as a place full of exciting possibilities, then it makes sense to look at the place that you’re leaving behind as a place with no future – particularly if you’re haunted by the reality of climate change, which is quite literally going to make that place uninhabitable for you.

There are definitely parts of this country that feel like they’re monuments and artifacts gesturing to the earliest days of the Republic. But then you look around and everybody’s moving out. Like everybody’s leaving. There’s nothing for anybody here.

Q. There was one piece of back-and-forth dialogue between two characters, Linc and Bugs, riffing about how you wouldn’t want to have been the first Black colonist on Mars. It was hilarious – how did you come up with that?

Something that I’ve been thinking about a lot is that no matter how far into the future we go, we’re always taking ourselves with us. And so many of our current pathologies and prejudices aren’t going to go away.

It was a lot of fun to write, because it also became, in many ways, a commentary on the sci-fi genre, which can have a paucity of imagination with regards to human behavior in these imagined scenarios, whether on a generation ship or on some other planet.

So rather than say all that in a very sort of ponderous, ultimately depressing fashion, it seemed like the best way – at least for me, spiritually and emotionally – to get that across was in this dialogue between these two young boys.

Q. Who do you wish would read “Goliath”?

That’s a really interesting question. When I write, I tend to write the book I’d want to read. But I mean – this may be sort of an easy answer – but it’d be really cool to put this in the hands of some legislators in Congress. I don’t know if it would change their opinions on anything, but maybe it could inform some decision-makers who actually have the power to help ameliorate, if not combat, the effects of climate change. I also hope Oprah reads it! Yeah, Oprah and the United States Congress.

Related Articles

In ‘Devil House,’ John Darnielle blurs true crime with blood-soaked fiction

The Books Pages: What we re-read, the week’s bestsellers and author interviews

How ‘The Golden Girls’ and a chance meeting led Maggie Rowe to ‘Easy Street’

In kids’ book, Sotomayor asks: Whom have you helped today?

This week’s bestsellers at Southern California’s independent bookstores