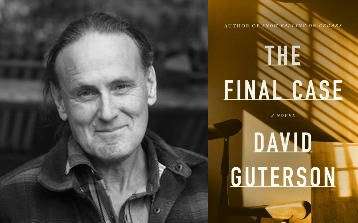

In David Guterson’s new novel, “The Final Case,” a White fundamentalist couple from outside Seattle is charged with abuse and the murder of the daughter they adopted from Ethiopia. An aging attorney named Royal agrees to defend the mother even though he finds everything about her distasteful.

At first glance, this may sound like it bears resemblance to Guterson’s debut novel from 1994, the award-winning, best-seller “Snow Falling on Cedars.” But that book was a taut drama structured around the crime and the case. Guterson’s latest novel, his sixth, is more haunting and elegiac. The case often seems secondary as the attorney and his son – who now must drive his father to work each day, and who narrates the story – take stock of their lives.

Related links

Viet Thanh Nguyen describes turning to crime for new novel ‘The Committed’

‘Orphan Train’ author Christina Baker Kline talks book party with Kristin Hannah and Elin Hilderbrand

Joyce Carol Oates talks Marilyn Monroe clones and more in ‘Night, Neon’ story collection

The Book Pages: Starting a new year of reading

Sign up for our free newsletter about books, authors, reading and more

“I wanted it to be reflective without wallowing, and it’s a fine line to walk,” Guterson said in a recent phone interview. “The word ‘maudlin’ shows up two or three times just to show the narrator is aware he’s on the edge of it.”

The narrator is definitely aware of our presence as Guterson deliberately blurs the lines between fiction and reality. The narrator is a novelist who has not written fiction for years. This is Guterson’s first novel in a decade. And the attorney is clearly modeled on Guterson’s father, a distinguished criminal defense attorney, whose outlook toward life and real-life cases are shared by his fictional counterpart.

The book opens with a disclaimer explaining that there was a real trial “but – to be clear – this book is a work of fiction.”

But then early in the first chapter, the narrator says, “Fiction writing was behind me in full… If that leaves you wondering about this book – wondering if I’m kidding, or playing a game, or if I’ve wandered into the margins of metafiction or the approximate terrain of autofiction – everything here is real.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q. On the surface, this book centers on a crime and a trial, which was also true of “Snow Falling On Cedars.” But that was a tightly focused drama and this one is not. Were you conscious of the connection and the differences and how readers might react?

I was conscious that the assumption of a plot focused on a legal drama would have suspense built around a verdict and that there would be an expectation that might be what holds this novel together and gives it narrative propulsion. But I wanted to undermine that expectation, I changed it so the trial is part of what I see as a larger story arc. I do understand how a reader feels like the narrative arc is buried but I definitely set out to write a novel that had a plot.

The reality of life isn’t consistent with fictional conventions, with plot points and a finite story. Life meanders. But I didn’t set out to meander. It’s just that the plot of the novel might take a little work to discover because it’s not necessarily on the surface.

I wanted to tell the story about the relationship between professional work – what we do to make a living – and the idea of striving for a meaningful life. The narrator has arrived at a moment where he’s confused and had a loss with regard to that. That’s the plot. The forward motion of the novel is him examining that relationship and the trial unfolds in the context of that larger story.

The trial is one more example of the relationship between work and a life with meaning and how it unfolds for the narrator’s father. We find that from the beginning of his career he has viewed every instance, every opportunity to find meaning in his work. This is the final instance of that in a career dedicated to that. That’s the buried arc.

Q. What drew you to the real-life trial?

About 15 years ago we adopted a girl from Ethiopia and the actual case in 2011 involved another adoption that happened about the same time and the people used the same agency as us and live in the same part of the country. Our daughter and the girl they adopted appear on the same DVD [that the agency sent to prospective parents]. So when I heard that the girl they adopted died in these horrible circumstances it hit me very hard. That could very easily have been our adopted daughter, she missed being in that position by inches. So I paid attention to the case and when the trial started in 2013 I attended every day; after the trial was over I went to Ethiopia and tracked down the family of this girl.

Q. Did you know you were going to write a novel about it? And did you know back then that you’d model the attorney on your father?

I knew I wanted to write something. I was so full of feeling about it all – it was in me in a deep way – but I didn’t know what, just that sooner or later words were going to come. The other piece is that the summer of the trial my father was in decline. He passed away that fall. Those two things got emotionally connected and you can see how that manifests itself in the novel.

Q. How did you decide what to keep fact-based and what to fictionalize? For instance, the actual family had adopted two Ethiopian children but in the book they only have the daughter.

I had some struggles and stops and starts in the writing trying to figure out how to approach the material. I did get a hold of every word of the trial transcript but there is no word for word, and the novel doesn’t contain any actual testimony.

Early on, I tried to have two adopted children because that was the reality. After a while, I realized the emotional energy of the story was being dispersed between two people so I had to eliminate one to focus on the other.

Q. You preface the book with a disclaimer saying it’s fiction and then your narrator almost immediately contradicts that, saying everything is real. Why are you saying, ‘Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain’ even as you draw the curtain back?

I legally needed the disclaimer and would not have put it in if I didn’t have to. I don’t think it really helps me in trying to convince the reader that they’re reading something real and probably creates some confusion. If a writer did it on purpose then maybe the reasoning would be that you can befuddle the reader about what’s real… and some readers might enjoy that. But I didn’t think of that.

There is a blurring of the line between the author and the narrator as there often is in first-person fiction and there are ways in which the narrator is me. Any fiction writer who works in the realistic mode is striving for a kind of verisimilitude, to convince the reader it’s all true and real. So any tool that helps make the reader think they ought to believe is a tool worth considering – opening with the notion that I don’t write fiction anymore is a tool because it subverts the natural tendency of the reader not to believe, to think, “If he’s not a fiction writer anymore, I must be reading non-fiction.”

Related Articles

Book Pages: Natashia Deón picks 3 great books, the Beatles’ top 100 and more

5 graphic novels to read now: ‘Tunnels,’ ‘Leonard Cohen,’ and more

How former Gawker writer Ken Layne became Joshua Tree’s Desert Oracle

This week’s bestsellers at Southern California’s independent bookstores

Matt Black’s ‘American Geography’ shows the lives of those struggling to survive