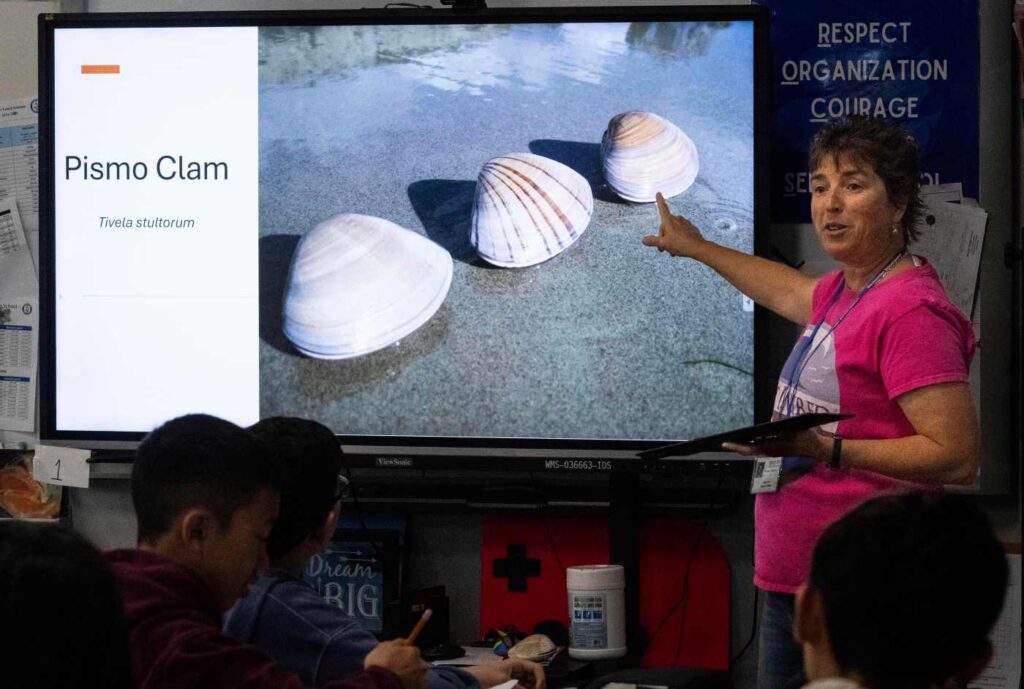

They are mysterious mollusks, a shellfish once abundant on sandy beaches across the state.

These days, Pismo clams are a rare find at the shoreline – but can the next generation of school-age scientists help bring the species back to the beach?

Students at Warner Middle School in Westminster are caring for the sea creatures, a first-ever effort to raise Pismo clams in a classroom outside of their natural environment.

The project was brought to the school by the nonprofit Get Inspired, implementing the same model used in past years to grow other sea life such as white seabass, abalone and kelp, an effort that gives a human helping hand to struggling species.

It was once a common pastime to bring a rake to the beach to scour for the Pismo clams, bounties of the shellfish readily available for the taking. But like many tasty sea critters, they were overharvested, their numbers dwindling through the decades.

Nancy Caruso, a marine biologist and founder of Get Inspired, started becoming curious about Pismo clams a few years ago and launched an effort to survey the current population numbers at local beaches. With the help of volunteers, teams have spent hours at a time armed with rakes at low tide when the ocean recedes and allows access to the damp sand to count the clams and radio tag at least some to track their movement.

The results haven’t been promising. In the past four years, 12 miles of beaches have been surveyed, with only 23 clams found that were larger than the legal taking size.

To legally take a clam from the shoreline, they have to be at least 4.5 inches, which typically takes about 15 years. The problem: they are often poached before reaching that mature age.

“We don’t have a lot of clams left, we know we overfished them,” Caruso said.”Now, can we get them back?”

A recent effort at Bolsa Chica State Beach just a few weeks ago involved 35 volunteers who tagged 100 small clams and reburied them.

“We hope to go back and look for them next year, to see how they move laterally up and down the beach,” Caruso said.

The Pismo clams being grown by the students, born in November, have been dubbed “Stripe, Creamy and Brownie.” They sit cozy in a pile of sand in a tank in teacher Travis Garwick’s seventh-grade science classroom.

Garwick, a department chair at Warner Middle School, has teamed with Get Inspired for various sea-themed projects over the last more than two decades. His classroom is dotted with aquariums and sea life.

Through the process of cultivating the clams, students learn about aquaculture, water chemistry, ecology and biology. They use a bright green algae brewing in a clear dispenser to feed the clams, measuring them regularly and documenting their progress.

If the classroom experiment is successful, and Pismo clams can successfully grow in a setting outside of the ocean, there could be a future where they are commercially grown, Caruso said.

Having the clams farm-grown and readily available would make the ones in the wild not as tempting to take, allowing the species to repopulate, she said.

Already, clams from the Northeast are grown in California, she noted. While markets in Baja, Mexico, still sell Pismo clams, it’s illegal to sell them commercially here.

“The clams we do grow here are not native. I think it would be cool if we could grow native clams,” Caruso said. “Everyone is excited about the possibility of being able to grow clams and have a new species we can feed people.”

Pismo clams, however, are a tricky species. Unlike other clams and mussels that grow in calmer harbor or bay waters, Pismos are found on the shoreline, a place with waves and sand where they bury themselves.

Caruso is also collaborating with Concordia University, where researchers are trying to spawn Pismo clams in a lab setting. They are trying to “trick” the clams using warm water to fool them into thinking it is summer, the time of year they like to breed.

At the Ocean Institute in Dana Point, researchers are trying to find out if they can be raised without sand. Growing the clams in sand is more challenging, because farmers wouldn’t be able to easily check on them to see if they are still alive.

“There’s a thousand questions we have to answer in order to put them out into the ocean,” Caruso said. “If we end up with 100,000 of those, we’ll start to outplant them … but I don’t know how big they will get. We’re learning all this.”

The Pismo clams serve several important roles in the ocean ecosystem. They work as a sand stabilizer, helping to keep grains in place to protect against erosion. They also act as water filters, cleaning an estimated 528 gallons of water per month.

The Pismo clams will stay in the class until the end of the school year, then be transported to the Ocean Institute or Concordia University while the students are on break.

“All my animals have summer school to go to,” Caruso joked.

Then, if they survive, they’ll return to the Westminster classroom for a new group of students to care for them next year.

“Three clams aren’t going to change the world, but the kids in this class are learning about Pismo clam and beach ecology and what they do,” Caruso said.

She tells the students: “It’s not a lost cause, you’re contributing to science by helping us figure out how to grow these things.”

The lessons empower the kids to look outside of a book for real-life applications, so they can identify problems and figure out how to solve them, said Garwick, an avid freediver and spearfisherman.

Though the Title 1 school is just a few miles from the ocean, many of the students have yet to visit the beach, he said. The various Get Inspired programs they have participated in over the years are an introduction.

More than 500 kids have learned to grow kelp through the Get Inspired program, with 250 volunteers who help to replant the kelp forests. The results this year were especially abundant up and down the coast.

The nonprofit’s work to restore green abalone and white sea bass also continues. The abalone effort started seven years ago, with the next step to obtain permits to outplant 5,000 abalone along the coastline.

The group has also released more than 1,200 white seabass grown by students in six schools, with more than 2,000 students involved, some learning to snorkel with the fish when they are released.

“To me, it’s just about being aware of what’s going on and believing in (the students) to be problem solvers of all things we screwed up,” Garwick said.

Student Ethan Nguyen, 12, said his big takeaway from the lesson is how important it is to preserve the animals in the ocean, and how challenging it is to preserve the Pismo clams.

Jordan Tigglebeck, 13, was especially intrigued by the clams’ water filtration abilities, he said.

“The stuff we do here, I feel like it’s important to the overall health of the whole world,” he said. “It makes me want to help things and see how beautiful they become because of our work.”

Related Articles

Sailing’s global grand prix brings cheers and gasps amid wins and close calls on San Pedro coast

Long Beach swimming areas closed due to Rowland Heights sewage spill

Olympian Caroline Marks, surf champion Tomson and Surfrider to receive SIMA honors

NOAA’s uncertain future brings tsunami of worry for wildlife, ocean

Kite party brings splash of color to the sand and sky in Huntington Beach