Sen. John Cornyn (R-TX) recently shot down suggestions from certain Trump advisors that the GOP further lower the corporate tax rate to 15 percent. This intraparty split on tax policy is not the first of its kind—it echoes conflicts that took place during the Reagan era.

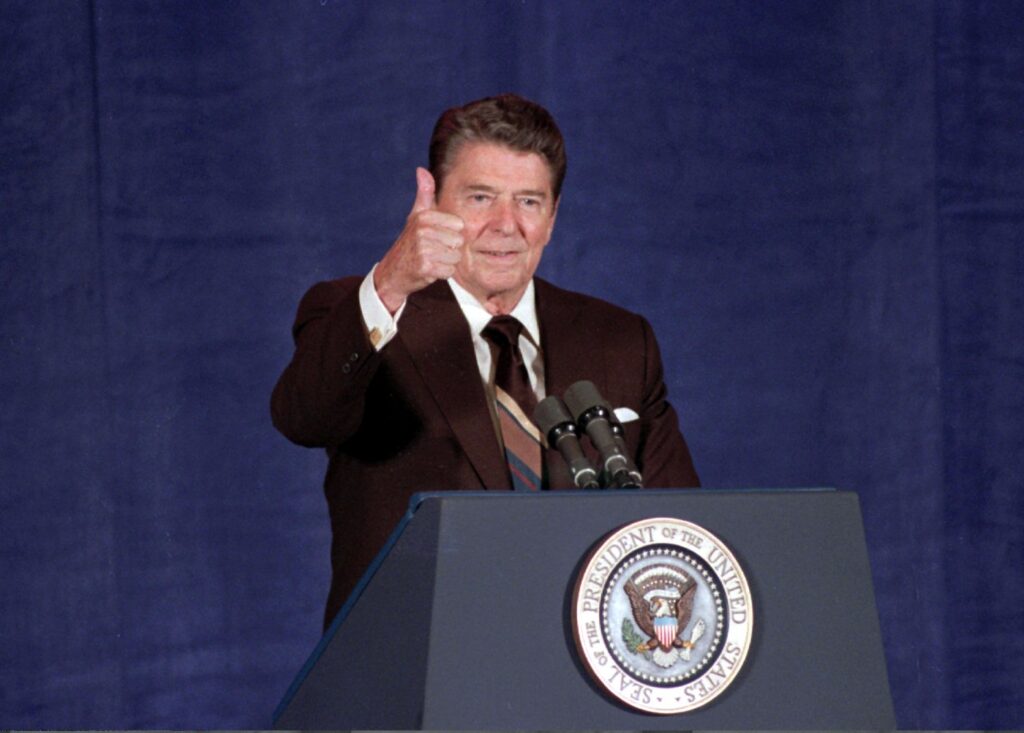

As the stage gets set for the next Republican debate, taking place at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, the party’s future leaders ought to consider the successes and misfires of the Gipper’s tax record.

Why the First Reagan Reforms Were a Success: The Triumph of ‘81

The most revolutionary reforms of the Reagan era were included in the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 (ERTA). The reform reduced the corporate tax rate from 52 percent to 48 percent, and reduced all individual tax brackets by approximately 23 percent, including the top tax bracket from 70 percent to 50 percent.

However, the cuts to tax rates were perhaps not the most important changes. Taxpayers today still benefit significantly from ERTA’s indexing brackets to inflation. In the high inflation environment of the 1970s, taxpayers were pushed into higher tax brackets, even as their real incomes remained flat or declined—a phenomenon called “bracket creep.” By requiring these tax brackets to adjust every year, ERTA has prevented this form of stealth tax increase.

The other important change in ERTA was the introduction of the accelerated cost recovery system, or ACRS. Typically, deductions for investment must be spread out over several years, rather than fully when the investment is made. Thanks to high inflation, and the opportunity cost of a delayed deduction, businesses cannot fully deduct the real value of investment. ACRS shortened depreciation schedules and allowed companies to deduct larger shares of their investments in earlier years, effectively reducing the tax burden on investment.

Improved cost recovery is one of the most effective pro-growth tax policies, as it only provides a tax cut for companies actively investing in the United States. And ACRS helped accelerate investment in the years following the passage of ERTA.

Between 1981 and 1986, Reagan made a few bipartisan deals to raise taxes to address fiscal concerns. Some of the compromises, such as the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982, slightly reduced the benefits of ACRS, but the broad contours of ERTA remained. Furthermore, the Social Security Amendment of 1983 stabilized Social Security for several decades, as the package raised the payroll tax while incrementally raising the retirement age and slowing benefit growth.

Where Reagan’s Tax Record Took a Wrong Turn: The Folly of ‘86

The true self-inflicted setback to Reagan’s tax base was not a net tax increase, per se. Instead, it was the allure of an even grander fix to the tax system: the Tax Reform Act of 1986, or TRA86.

TRA86 is often hailed as a great triumph of bipartisanship, and at least on the individual side, it made significant improvements. It condensed a complex 16-bracket income tax schedule to only two brackets and dropped the top bracket from 50 percent to 28 percent. It also introduced new limits to various itemized deductions.

The corporate side of the reform, on the other hand, was a mess.

TRA86 further reduced the corporate tax rate, from 46 percent to 34 percent. However, in order to “pay for” this rate reduction, the package rolled back much of the improvements to the tax treatment of investment passed in 1981, as ACRS was replaced by the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS). On net, the changes penalized new investment and negated the economic benefits of the lower income tax rates.

The economy wavered in the late 1980s, and investment in certain sectors, such as multifamily housing construction, has never rebounded. The lower rate and worse tax treatment of investment also benefited relatively capital-light retailers at the expense of capital-intensive manufacturers.

The Lesson for Presidential Candidates Today

Related Articles

Compromise will boost fast food costs

John Stossel: Did you survive the budget cuts from the last debt ceiling fight?

The California Board of Registered Nursing must not vote to limit nursing school enrollment

Few California workers belong to unions, but they scored big in Legislature this year

Flag policies established for TVUSD school property: Letters

This brings us back to the tax debate taking form in the Republican primary. While lowering the corporate tax rate is not a bad idea, an excessive focus on lowering the corporate tax rate can come at the expense of other reforms. As seen in the Reagan administration, lowering the corporate tax rate required undoing some successful tax reforms the administration previously enacted.

In a scenario where the GOP holds a trifecta following 2024, they will face similar decisions regarding priorities. At the end of 2025, large portions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) will expire. Additionally, the TJCA temporarily introduced 100 percent bonus depreciation for short-lived assets, although it began phasing out at the beginning of this year. Meanwhile, as an attempt to juice the TCJA’s revenue score, policymakers introduced a tax penalty for R&D that took effect in 2022.

Given limited fiscal space, Republicans will have to pick which tax cuts to extend. Prioritizing expensing for R&D investment and 100 percent bonus depreciation would extend the legacy of ERTA. But being distracted by a further reduction to the headline corporate tax rate, without consideration for how the tax base hurts investment, would be a replay of the follies of 1986.

Alex Muresianu is a federal policy analyst at the Tax Foundation, a nonpartisan think tank in Washington, D.C.