In the opening pages of Tom Rachman’s “The Imposters,” we meet an aging British couple, Dora and Barry—she’s a novelist with a small and diminishing audience, he’s a divorce lawyer turned couples therapist. Their scenes are emotionally nuanced and grounded until the moment Dora is waiting for Barry to come downstairs.

“Nobody comes downstairs. Nobody is upstairs, or anywhere else in this house,” Rachman writes. “Only Dora, pondering a fictional character, this husband Barry, based on someone she met in passing once, and written into a story that isn’t quite working, as none of her stories quite work anymore.”

Related: Sign up for our free newsletter about books, authors, reading and more

Rachman enjoys gently tugging the rug underneath the readers throughout his book as Dora faces her cognitive decline and tries to finish one last novel before taking her life. In between hearing directly from Dora in her diaries, we read lightly connected chapters that read as short stories about people from Dora’s lives, from her daughter to a deliveryman.

Dora is not reporting truthfully but conjuring up new worlds and relationships for these people as she grows increasingly isolated, particularly as Covid sends the world into lockdown.

Some of her stories are comedic, like the story of Danny, another struggling novelist who makes one faux pas after another at a literary festival, while others are deadly serious, like the story of Amir, who tries returning home to Syria for his father’s funeral only to be detained and tortured. We eventually get glimpses of the “real” people beyond these imposters.

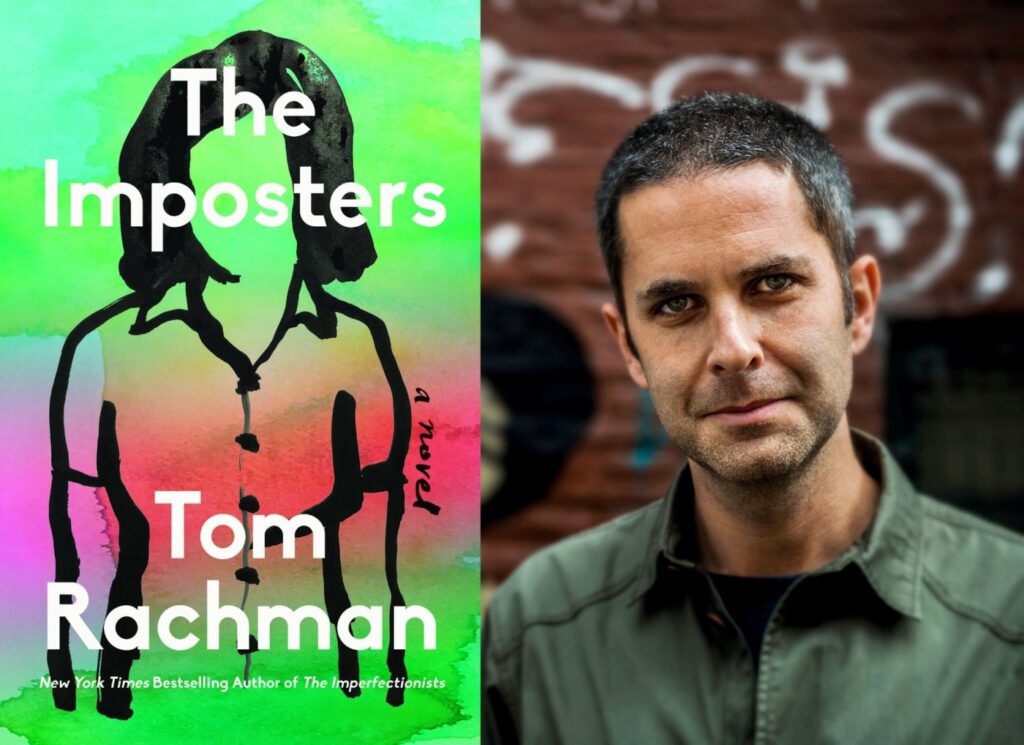

This is the fourth novel by Rachman, and it hits stores June 27. His first, “The Imperfectionists,” centered on newspaper journalists and was a best seller. All of his books, which include “The Rise & Fall of Great Powers” and “The Italian Teacher,” earned critical acclaim and share some thematic similarities.

“It isn’t conscious, but I’ve noticed that I keep writing about the culture, both in terms of the arts and in terms of political culture,” Rachman said in a recent video interview from his home in England. “I was a journalist for a long time, so I feel quite connected to the political world and the history that’s breaking around us. I also have a professional and personal interest in what’s happening to the arts.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q. Your characters often feel isolated, even, or especially, from their families. That’s especially true of Dora.

The loneliness of the characters pushes through all these books. Many are desperately yearning for human connection and sometimes they’re woefully disappointed with what they’ve found in their family. Like Dora, they’re looking out the window at other lives.

I felt that had a resonance during the pandemic, which is when I was writing. A writer—Dora, or me— spends all this time looking at a screen and imagining people and the larger world and then bringing them to life on that screen. You’re in isolation but surrounding yourself with humanity. You can see everything going on all at once online but you also feel like you’re missing out. Covid seemed like a strange echo of this life.

Q. Do you feel isolated when you’re writing?

I can never tell if writing is a pathetic attempt by me to escape or if it’s an enrichment of life. When I’m doing it, it feels blissful, being lost in my imagination, conjuring things, taking aesthetic pleasure in trying to piece it all together. But I also do it to escape the world sometimes. In terrible periods of my life, I’d disappear into the story.

Q. One character says, “That’s the real midlife crisis: You’re irrelevant.” Do you worry about that for you and for novelists in general?

The question of relevance is at the heart of this book. In our society, it feels increasingly like literature is in a marginal place and that’s saddening to me. When I was young, I dreamed of accessing the literary world. Now that world is smaller and less pertinent. The age when a novelist could have imagined being on the cover of Time magazine is now as unimaginable as actually reading Time magazine.

Separately, I’m constantly thinking, maybe it’s just me. People might roll their eyes and say, “Novels aren’t dead, just your perspective.” I’m open to that possibility. Either way, it’s not good news.

Q. This novel feels darker than your others. Was it the pandemic, existential issues like the climate crisis and democracies faltering, or things going on in your life that fed this mood?

It’s all the things you just said. The book has humor all the way through but this does feel like a world in jeopardy — the absolute chaos that climate change is bringing, the extremist politics shredding democracy, which is making people lose faith in the system and human beings, and also the elements of technology that arrive as marvels but transform our lives in ways that aren’t marvelous. It feels like things are out of our control now.

And I was writing when the pandemic hit. It also speaks of a darker time in my life. I was having a hard time and struggling to write and all that came out in the book.

Q. What motivates Dora as she works without a publishing deal and while fretting about her cognitive decline?

It seems like she’s trying to recall and recount her life but then you realize it’s more of a way to correct or amend it — not necessarily better it in every case but to try and revise reality. Dora is trying to create the life she wanted. Writers are often looking for characters on the page that accord with the world they’d like or the world they understand.

She longs for that fictional Barry to live with her but knows she couldn’t have lasted two weeks with him. She’s looking back and wondering if she got it all wrong and whether she could have done things differently or if that’s just who she is.

Q. As Dora creates characters based on real people, were you trying to get us thinking about how novelists utilize real people in their books?

It is a playful way to mess around with that. There’s an odd interplay between what’s real and what the writer creates.

With my first book, people kept saying, “You based this character on so-and-so” with absolute certainty. But what happens is I take tiny little details that are true — like the way someone holds their pencil — but then the character takes on a separate life. When I first started out, if I’d get stuck I’d base a character on somebody I know, but those characters were always terrible. They never came to life.

Q. In one lighter moment, Danny says to Dora, “I might be one of your characters” to which she retorts, “Oh, you are. Are you only realizing that now?” That felt pretty meta.

I enjoy playing with that ambiguity — it’s meant to make the reader pause and wonder, but I didn’t do too much of that because it separates the concept from the story. You want the reader to be in the story and only occasionally to think from a different angle. If you just are pointing out the artifice, it can become an ironic display that’s irritating to read.

Q. Are you often thinking about people as potential characters?

There’s often a dissonance between the superficial thin version of people you encounter during the course of your day and the certainty that there’s a huge amount more in everyone’s lives, whether it’s your bank teller or bus driver. Writers are curious about other people’s lives, about getting into their rooms, their thoughts and their hearts.