Republican politicians need to get some new material.

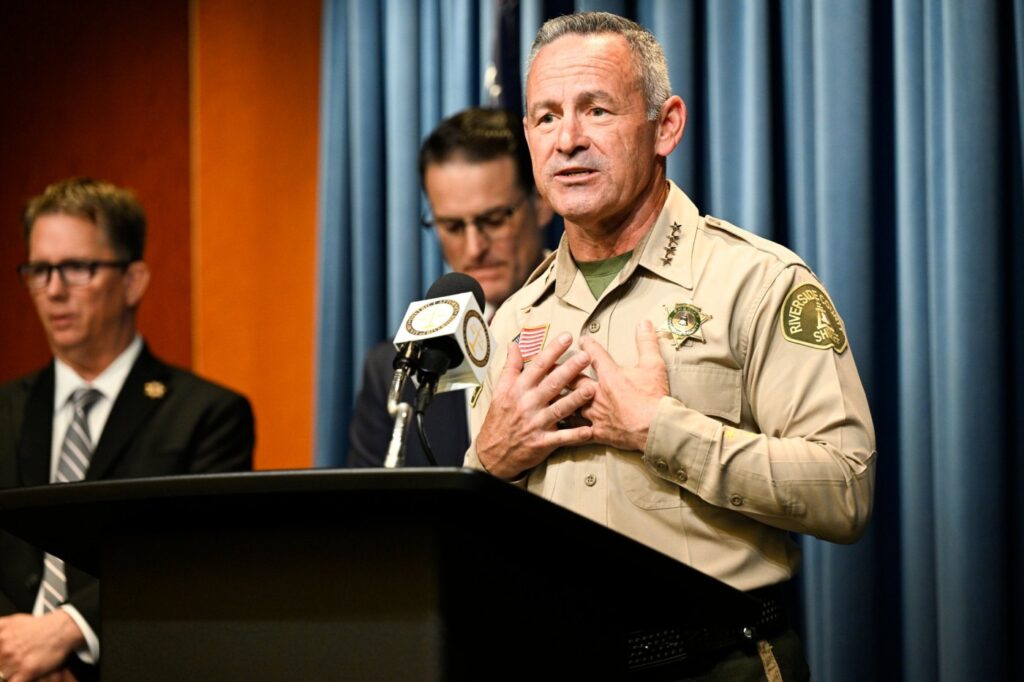

On Wednesday, Riverside County District Attorney Mike Hestrin and Sheriff Chad Bianco held a news conference to complain about crime and called on the state to revisit criminal justice reforms so more people can go to prison.

“They don’t care what we think, they care what voters think,” said Sheriff Bianco, according to ABC 7. “Until we can get the voters fed up and the voters start calling them, it is not going to change.”

Bianco should take the lack of voter interest in the tough-on-crime message as a hint that most Californians don’t actually think the sky is falling.

A walk through some history is important.

In 2011, California passed Assembly Bill 109 to send more low-level offenders to the local level to handle.

The following year, Californians approved Proposition 36 to bring reasonable reforms to the “three strikes” system so that no one is sentenced to life imprisonment over a non-serious crime.

In 2014, Californians approved Proposition 47 to reduce a handful of drug and property crimes from felonies to misdemeanors so that our prisons and jails won’t be full of really low-level offenders. Thanks to Prop. 47, half a billion dollars in reduced incarceration costs have been freed up and reinvested in crime prevention and drug treatment.

In 2016, Californians approved Proposition 57 to help incentivize prisoners to participate in rehabilitation programs so they can earn credits for earlier parole consideration. The horror.

Law enforcement groups generally opposed all of the previously mentioned reforms. They have been complaining about increased crime ever since 2011 and warned about a wave of crime specifically caused by criminal justice reforms ever since.

In 2020, they put forward Proposition 20 to reform the criminal justice reforms. If Californians shared the view of Bianco and Hestrin that criminal justice reforms were so bad, you might expect Prop. 20 to have done alright. Instead, it was rejected by nearly 62% of voters. And, by the way, a majority of Riverside County voters.

How could this be, if crime is so bad?

Well, for one, the crime picture is somewhat muddy.

From 2012 to 2021, violent crimes in Riverside County did go up, from 6,989 to 7,511 in 2019 and then down to 7,201 in 2021. Property crimes fell from 68,176 in 2012 to 57,986 in 2019 and again to 50,113 in 2021.

That’s something; violent crime is bad and any increase of it is bad, but is that enough to draw any sweeping conclusions from?

Related Articles

Why do California’s progressives want to gut our direct democratic tools?

Decarceration movement hits a speed bump in Los Angeles County

California cracks down on press access, our right to know

Douglas Schoen: Democratic wins in midwestern elections offer the party a roadmap for 2024

The wrong kind of security guarantee for Ukraine

Over that same time period, the county’s population grew by about a quarter of a million people.

Nor is it clear that justice reforms are the driver of crime increases. It’s not like Riverside County or California are unique in seeing increased violent crime in particular — violent crime has edged up across the country since 2014, according to a December 2022 report from the Congressional Research Service.

Of course, is it possible that some of California’s current criminal justice policies could be tweaked to hold particularly troublesome criminals accountable? Sure.

But it’s also clear that Californians don’t support mass incarceration, do support greater investments in alternatives to incarceration and don’t buy the idea that sending more people to rot in prisons is the way forward. Hestrin and Bianco might not like that, but it’s the truth.

Sal Rodriguez can be reached at [email protected]