As California prison populations decline, facilities across the state are being slated for closure, threatening economic devastation for communities where they are located. Rather than fight closures, the affected cities and those concerned about them should find alternative engines of employment, and state policymakers should be willing to help.

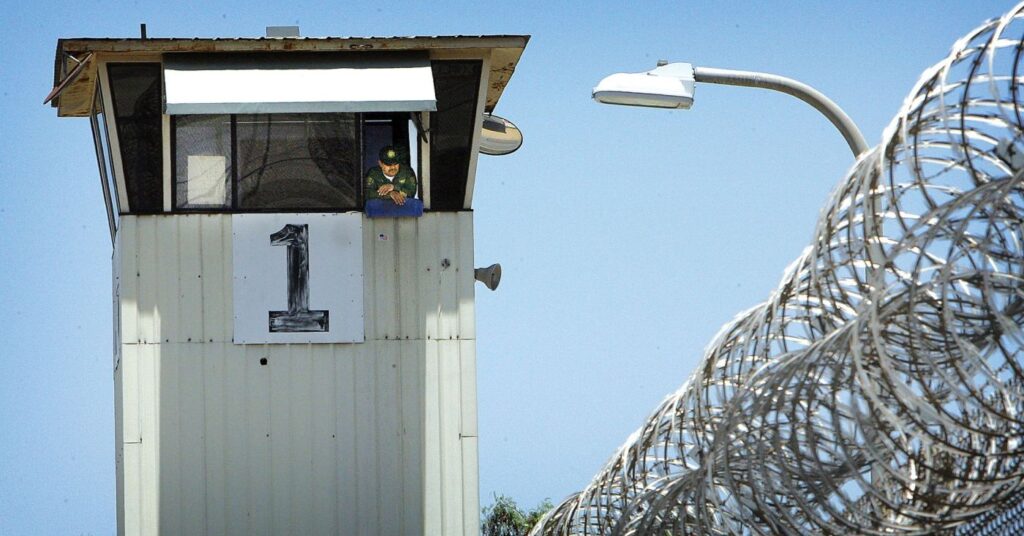

The statewide prison population declined from 168,000 in mid-2009 to 96,000 in late 2022. Initially, the fall in population was necessary to address a chronic prison overcrowding problem, which had resulted in a federal court order against the state. But once overcrowding was resolved, further population declines have resulted in empty cells.

By concentrating the remaining inmates into fewer facilities, the state can save money by eliminating the need to maintain and staff prisons that are no longer needed. Assuming that decarceration is the right policy, prison closures are the most cost-effective way to implement that policy.

Critics of decarceration are concerned about newly released inmates committing violent crimes, but the state’s overall crime rate remained near multi-decade lows in 2021.

Next year, the state will close the California Correctional Center in Susanville, a small city in the far northeastern corner of the state. Also on the chopping block are portions of facilities in Blythe and Norco (Riverside County), Tehachapi (Kern County), and Crescent City (Del Norte County).

Although none of these small communities are losing their entire prison capacity (a second facility is remaining open) for the time being, they remain at risk of severe distress given the high share of employment related to incarceration.

These communities may be able to retain residents and attract new industries if they can offer a more affordable cost of living and doing business. Unfortunately, they are trapped in a relatively high-cost state. For example, California’s state minimum wage is $15.50 compared to $12.80 in Arizona and $10.50 in Nevada, whose border is not far from Susanville.

California also imposes a variety of business and labor regulations not mirrored in neighboring states. For example, AB5 makes it more difficult for businesses to use independent contractors, obliging them to instead rely on employees who must receive paid sick leave and other mandatory benefits. While many businesses in economically vibrant areas of California have been able to shoulder high labor costs, firms operating under weaker economic conditions may not be so fortunate.

Finally, California’s personal and corporate income tax rates are higher than those in neighboring states. This makes it hard to retain businesses as well as remote workers who can readily move across state lines.

Given California’s current political alignment, it seems unimaginable that tax rates, minimum wages, independent contractor restrictions, and other impositions will be rolled back statewide. But perhaps lawmakers could be convinced to allow exemptions in distressed areas such as those struggling to recover from prison closures. Aside from offering a lower minimum wage and more AB-5 exemptions, the state could also consider allowing businesses and remote workers in distressed cities to exclude a portion of their income from state taxation.

Related Articles

It’s time to make the California state budget leaner

The real cause of California’s homelessness crisis

Congress has a fiscal road map, it just needs to use it

Trump’s ‘free speech’ plan is overreaching

A new try for unionization of legislative staff

California has some history with special economic zones in depressed areas. In 1984, the state created an enterprise zone program that offered hiring tax credits, sales tax credits and deductions for business expenses and interest income. The program ultimately included 42 zones and reduced state revenues by as much as $600 million annually before it was repealed in 2013. A new enterprise zone program focused on a smaller number of communities, especially those dealing with the after-effects of prison closures, and prioritizing regulatory relief over tax credits could be implemented at a much lower cost.

For the Susanville closure, the Newsom administration has announced an economic response, but this mostly involves finding new jobs for prison employees elsewhere in the state system and grant programs targeting selected industries. A better option is to lower the cost of working and doing business in the area so that as many establishments as possible can survive.

Marc Joffe is a federalism and state policy analyst at the Cato Institute.