“The sky is full of planes, diving and zooming over the hangar line,” wrote Army pilot Lawrence M. Kirsch, describing his view of the shocking attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

“It’s like watching a newsreel. It doesn’t seem possible. It can’t be true. Something’s crazy.”

Words so full of emotion and terror paint a picture of the attack with a writer’s eye. Kirsch had worked as a reporter for the Pomona Progress-Bulletin and the Brawley News prior to joining the Army Air Corps in 1940.

What he has left us with is a typewritten, six-page recollection of that day that for years has been kept safe by his sister-in-law, Barbara Kirsch, 92, of Yucaipa. It’s believed he composed this shortly after the attack.

RELATED: In his own words: Army Air Corps pilot describes chaos and fear after attack

She let me read his words – under the heading “War – First Day” – that have been kept in a large notebook. It holds photos and wartime memorabilia of her late husband Ralph L. Kirsch, a Navy officer in the Pacific during the war, as well as his brother Lawrence.

“I have been told by others who have read it that it was something special,” explained Barbara Kirsch. And the words by her brother-in-law do offer intimate detail of his steps on that dramatic day in world history.

Army pilot Lawrence M. Kirsch (Photo from a 1944 Pasadena newspaper)

Lawrence Kirsch was asleep in his barracks that Sunday when he was awakened first by the sound of many planes passing over followed by a series of explosions. He would finally make it to the flightline there in Honolulu to observe aircraft and buildings on fire or destroyed. He actually got a barely flyable plane into the air, but by then, the Japanese attackers were long gone.

What was left was a “pitiful sight,” he wrote.

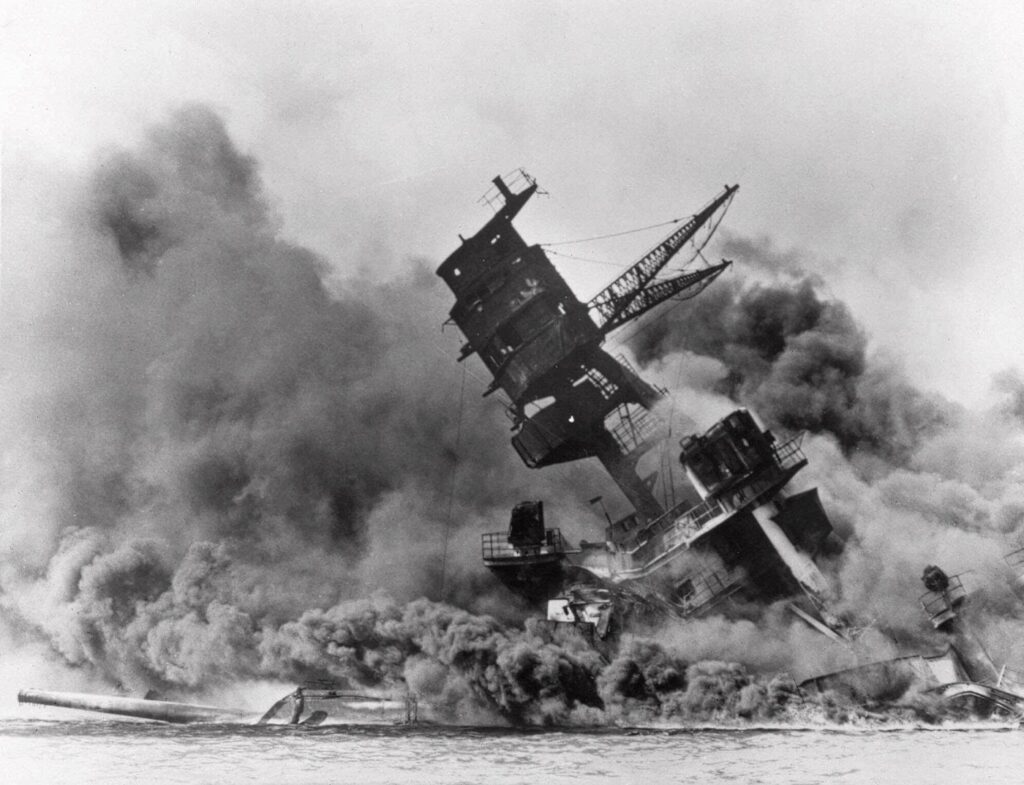

“Skirting Pearl Harbor – invulnerable Pearl Harbor – we look out on the still-burning Arizona and other sunken ships,” describing the view as he watched later in the day. “One’s huge, bare bottom is turned skyward, another pair is sunk to their rails and titled at crazy angles.”

Earlier, Kirsch, who grew up in Altadena and attended USC, came close to being a casualty of the attack. He and two other pilots had jumped into a car and were headed for their hangar when they saw a Japanese fighter plane diving right at them.

“It looks as if it will dive straight through the windshield,” he wrote. “The doors burst open and we scatter like a bunch of rabbits. One of the pilots tells me later that bullets actually kicked dirt into his eyes as he lay prone.”

They arrived at the field just after the Japanese planes were finishing their attack on the parked planes and hangars. Aviation fuel trucks were on fire, ammunition was blowing up in all directions.

“Running down the last fifty yards … is like descending into some noisy black and red pit,” he wrote. “Row after row of parked P-40s, standing like patient blind men, are ablaze from the incendiary bullets. I feel like they have been awaiting a terrible and known doom.”

The shattered wreckage of American planes bombed by the Japanese in their attack on Pearl Harbor is strewn on Hickam Field, Dec. 7, 1941. (AP Photo)

Amid such terror, Kirsch and other pilots searched any planes still able to fly.

“The first plane I try to start grinds furiously and refuses. Gas drains from the holes in the tank and I sit on windshield glass which has fallen on the seat.”

Pilots and other soldiers struggle to move planes – broken or still flyable – away from the burning debris. For some it was far more of an experience than just pushing around metal debris.

“They were the planes we had learned to fly, to stunt and to shoot,” he wrote. “We had cussed them, mistreated them – but somehow there was a bond between us. They were defenseless friends, butchered without warning.”

Even in the utter confusion, there were brief light moments. To douse a burning fuel truck, Kirsch was handed a fire hose. “Aha! One of my lifetime ambitions is fulfilled – I am working a fire hose.”

In the confusion, he noticed that rank didn’t seem to mean much. “One private, very eager, is big and loud and believes he is running the whole business. The captain is standing next to him and gets orders from the private to move the cases along faster. I’m forced to grin.”

Early on, the men hear some of the confusing and mostly wrong information from local radio. “Alarming reports are coming in from the Honolulu radio station: Jap troop ships flying the American flag; a major first engagement southwest of the island; parachutists landing at Barbers Point. We don’t relish the thought of being prisoners for some years to come!”

Kirsch and another pilot were that afternoon assigned to drive to Bellows Field, which was away from Pearl Harbor, to replace two pilots killed in the attack there. It was from there he was able to fly a patrol that day.

A Japanese plane was shot down during the attack about a half-mile from the field. “In later hours, about fifty-three persons claim to have made the shot that got it: one lieutenant with a shotgun, a private with a pistol, a civilian with his rifle, a ground machine gunner, all were sure they are the killers!”

After landing from his patrol, Kirsch was resting when a mysterious light was reported on the end of the runway. As they feared a Japanese ground attack, everyone grabbed weapons and hid behind sand dunes – “like boys playing cops and robbers” – prepared to meet the enemy. It turned out the object of their concern was merely a crouching military guard – “almost too scared by the ruckus to talk.”

As he tried to sleep, Kirsch said two prisoners were brought near his tents. They were Japanese farmers who had been using lights in a cane field – similar to Southern California at the same time, anyone Japanese was immediately suspected of signaling the enemy.

“What a long day it’s been. I am too exhausted to review it all; too glad to be in bed to think of what the day’s doings may mean to history and to our own futures,” he wrote. “I feel at peace; that they will not come back.”

Lawrence Kirsch would go on to fly 130 combat missions during the war with the Army Air Corps. Barbara Kirsch said she was told he became an ace for shooting down at least five enemy planes in combat. He was the recipient of a Silver Star, Distinguished Flying Cross and an Air Medal. After earning the rank of major, he would later be assigned to administrative service at Chico Army Air Field in Northern California.

The remainder of the Kirsch family of Altadena also provided valuable service in World War II.

Lawrence’s brother, Ralph, served as communications officer of the amphibious force command ship USS Mt. Olympus which later was in Tokyo Bay for the signing of Japan’s surrender agreement in 1945. Barbara Kirsch said he later turned down a promotion to lieutenant commander and decided not to remain on the Mt. Olympus which was due to be part of Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd Jr.’s expedition to reestablish a U.S. base in Antarctica.

A third brother, Kevin served as a surgical technician at Fort MacArthur in San Pedro while a sister Therese was an anti-aircraft gunnery instructor at Newport, Rhode Island, during the war.

Joe Blackstock writes on Inland Empire history. He can be reached at [email protected] or Twitter @JoeBlackstock. Check out other columns at Inland Empire Stories at www.facebook.com/IEHistory.