Saturday marks exactly 50 years since the Olympic basketball debacle in Munich, a gold-medal game in which the United States appeared to have beaten the Soviet Union – and maintained what was to that point a perfect 63-0 record in Olympic hoops – only to have it reversed after referees (and administrators) gave the Soviets three tries to get it right.

Some wounds will never heal. The United States players, to this day, have refused to accept the silver medals from that tournament. They’re still in a vault somewhere, and I think we can assume hell will freeze over before that changes.

“They (Olympic officials) said in order to get the medals, everybody has to accept it,” said Ed Ratleff, a two-time first-team All-American at Long Beach State and later first-round pick of the Houston Rockets who was part of that team. “And I know there’s no way I’m gonna accept it. Kenny Davis (the team captain) has put it in his will that nobody in his family can accept it.

“I tell people, my mother taught me at a young age that you don’t take anything that doesn’t belong to you. That silver medal did not belong to me, so I can’t take it.”

The Soviet Union basketball team, flanked by the bronze-winning Cubans, right, stands on the podium after receiving their Olympic gold medals Sept. 10, 1972, in Munich. To their left is a vacant place where the U.S. team was supposed to appear but refused their silver medals. (Pool photo via AP, File)

It was a bizarre finish to a bizarre game in a bizarre Munich Olympics, which turned tragic on Sept. 5 when eight Palestinian terrorists entered the Olympic village, killed two Israeli athletes and took nine others hostage, eventually killing the rest when a rescue attempt went awry.

Ultimately, that terrorist act would change the Olympic movement and particularly the International Olympic Committee’s emphasis on security. But for the time being any reflection was brief. After a 34-hour stoppage, including a memorial service in the main stadium, then-IOC president Avery Brundage brusquely – and, to many, insensitively – insisted, “The Games must go on.”

“We heard all the action that night but we didn’t know what it was until we came in the next morning on the way to practice, when they told us,” Ratleff said in a phone conversation. “I thought it was firecrackers and people having fun at the disco, which wasn’t too far from our dorm.

” … You’d see some of the athletes at the Olympics walking by. Some of them you don’t talk to because of the language barrier, but you kind of know them, and you wave to them and stuff. After that happened, it really threw us back. You look at yourselves. It could have happened to us just as easy.”

The men’s basketball final – the women’s game wouldn’t join the Olympics until 1976 in Montreal – was to be the final medal to be decided in those Games. For a time, Ratleff recalled, there was uncertainty whether the basketball final would be played until Brundage made his proclamation.

It was a clash of systems: the amateur college athletes representing the USA against the older, state-subsidized “soldiers” and “students” of the USSR, the matchup framed as capitalism vs. communism during some of the darkest moments of the Cold War.

Beyond that, there was an internal clash. Even as some of the more heralded college players of the day (including UCLA’s Bill Walton) opted not to try out for the U.S. Olympic team, the roster was filled with athletes eager to play a fast-paced game … but it was coached by a veteran college coach, Henry Iba, who insisted on a slow-it-down style. Ten passes per possession was, seemingly, the ironclad rule.

“(Future NBA player and coach) Doug Collins was my roommate at the Olympics, and he and I are sitting together on the bench,” Ratleff related. “They had a zone against us and the guys wouldn’t shoot the ball. So they told Doug to get into the game and shoot the ball, saying, ‘We need some shooters in there.’

“So Doug gets in the game, the ball comes to him after one pass, he pulls up and shoots the jump shot, and no sooner had the ball left his hand than Iba’s saying, ‘Get him out of there.’ Doug comes back – we laugh about it still. It was funny because he comes back to me with almost tears in his eyes, going, ‘Didn’t they tell me to shoot the ball?’”

Iba had coached 40 years of college basketball, 36 of them at what was then known as Oklahoma A&M (now Oklahoma State). He had 752 career college victories, two NCAA championships (1944-45 and ’45-46) and two Olympic championships (1964 and ’68), and was available and willing to coach the team in an era when not everybody would.

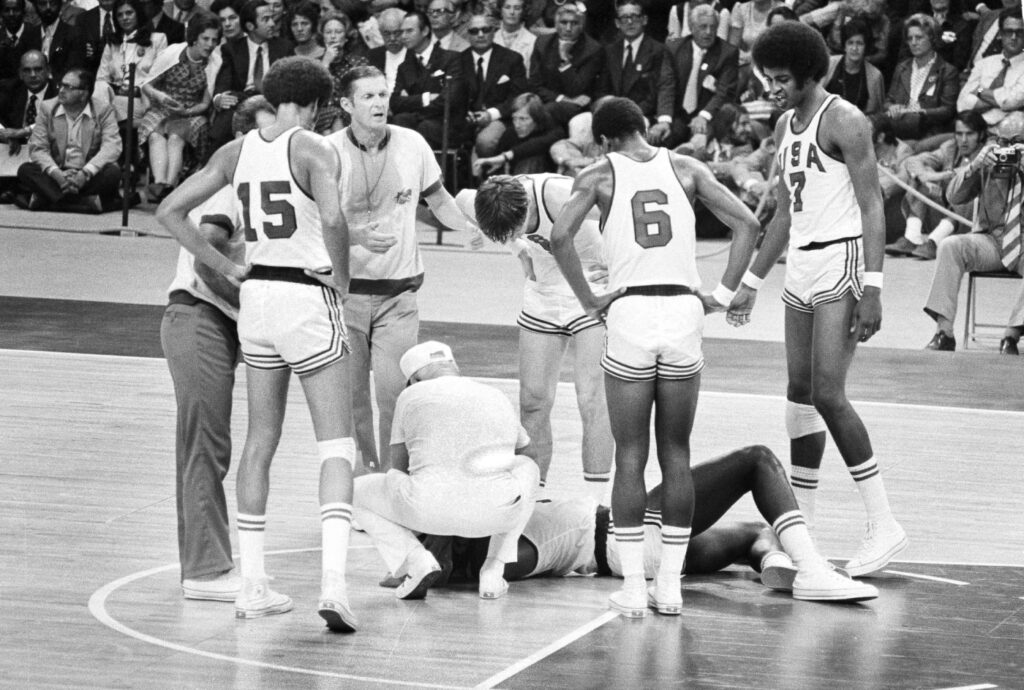

U.S. Olympic men’s basketball coach Hank Iba, left, looks over the shoulder of referee Artenik Arabaijan as he explains to the official the circumstances of the final seconds of the gold-medal game won 51-50 by the Soviet Union on Sept. 10, 1972, at the Munich Olympics. (Staff/AFP via Getty Images)

“They didn’t ask the coaches to coach,” Ratleff said. “The coaches came to the Olympic committee asking if they could coach the team. John Wooden was not asked to coach the Olympic team, and there’s no way John Wooden’s going to come and ask to be coach.”

But the game had changed and Iba hadn’t kept up. And the roster that came out of the U.S. tryouts – including future pros Mike Bantom, Jim Brewer, Tom Burleson, Tom Henderson, Dwight Jones, Bobby Jones and Tom McMillen as well as Collins and Ratleff – was hardly suited for the tempo on which Iba, then 68, insisted.

During that gold-medal game, the Soviets jumped out to a lead and maintained it, leading 26-21 at halftime and by 10 points with 10 minutes to play. At that point, the USA players themselves changed the script, applying defensive pressure and whittling down the lead. Iba and his assistants, Don Haskins and John Bach, said nothing.

“At that time we were catching up to them, making steals and stuff, he (Iba) just let it go,” Ratleff said. “I think it happened too fast for him, I really do.

“I liked the coach. Nice man. I think one time he was a great coach. I just thought at that time, the game had passed him by for the style of play he wanted to run. You can’t play that style of play with the players that we had. I’m sorry.”

Interestingly, before the game, Iba wrote “50” on the blackboard in the Americans’ locker room. The message, Ratleff said, was that 50 points would win the game. It seemed prescient at game’s end when Collins was undercut on a fast break, stepped to the line and made both his free throws to give the U.S. a 50-49 lead with three seconds left.

This is where the chaos began.

As Collins released his second free throw, a horn sounded. And when the referee waved for the Soviets to inbound the ball, USSR assistant coach Sergei Bashkin leaped to his feet and ran to the scorer’s table to complain that head coach Vladimir Kondrashin had called a timeout. The problem: In international rules at that time, the timeout – activated by pressing a button next to the bench or by notifying someone at the scorer’s table – could be taken between free throws or after the second free throw, but it had to be requested before the free throws. The Soviets said Kondrashin had pushed the button before Collins’ first foul shot, but there was no communication from the scorer’s table to the officials.

So, after the ball was inbounded and two seconds elapsed, play was halted. In the chaos – in which FIBA secretary-general Bill Jones of Britain claimed there was a human error resulting in the timeout request not being relayed to the referees in time – the Soviets had time to design a play and, at Jones’ behest, the clock was supposed to be reset to three seconds.

Before the second inbounds pass, Kondrashin snuck a substitute into the game, Ivan Edeshko, even though technically no timeout had been granted and thus no substitution was permitted under the rules. Edeshko’s job was to throw a length of the court pass to Aleksandr Belov. The officials allowed Edeshko to inbound the ball even though the clock, as shown on the ABC telecast, still hadn’t been reset at :03 and in fact showed 50 seconds.

After Edeshko’s length-of-court pass went off of Belov’s hand, the horn sounded and the Americans started to celebrate. But the refs – and Jones – conferred again and decided that since the clock hadn’t been reset, three seconds would be put back on the clock.

Members of the U.S. Olympic men’s basketball team prematurely celebrate what they thought was a victory over the Soviet Union in the gold-medal game of the Munich Olympics on Sept. 10, 1972. (Staff/AFP via Getty Images)

“I’m sure if they’d missed it then, I wouldn’t be surprised if they’d let it go back for a fourth time,” Ratleff said.

The U.S. players were tempted to go to the locker room anyway and dare the officials to say anything about it. But Jones “said we had to play,” Ratleff said. “We were gonna go in. We’re done. But he said, ‘If you go in, you’re gonna forfeit the game, and if you go in the United States may not be invited back to the Olympics again in basketball.’”

Whether Jones had that power, we don’t know. But they ran the play again. This time Belov caught the ball between two defenders, knocked down Brewer with an elbow and made the shot before the buzzer for a 51-50 USSR victory. (Edeshko stepped on the end line as he was launching his length of the court pass, as the ABC clip showed, but that also went uncalled.)

The Soviet Union’s Aleksandr Belov scores the winning basket to push his team past the United States 51-50 in the gold-medal game at the Munich Olympics on Sept. 10,1972. (AP Photo)

The Americans protested. FIBA’s five-member jury of appeal upheld the USSR victory, reportedly by a 3-2 vote. (The vote was never officially revealed, but the representatives from Italy and Puerto Rico revealed that they’d dissented. The others were from Hungary, Poland and Cuba, all part of the Eastern Bloc.)

And that “50” Iba wrote on the blackboard turned out to have significance after all. It was the USSR’s 50th gold medal of those games.

“They know that (the U.S. won), and we know it,” Ratleff said. “But back in that Cold War time, for them, it was like they had to have a win. So when they go back with this win, doesn’t matter how they got it. They don’t care. They were put on pedestals like kings.

“In the United States, if we go back with the gold medal, we’re just gold-medal winners. The next day, it just goes on like it was before.”

Related Articles

Investigators interview Teri McKeever as part of bullying probe

New USC throws coach Martin Maric was previously banned for doping

UC Berkeley swimmers: Leaders failed to take action against Teri McKeever for decades

Swimmers voice concerns about focus of Cal’s McKeever probe

A look at the Rose Bowl’s 100-year history

But changes were coming. The U.S. convincingly won in 1976 in Montreal with Dean Smith in charge and 1984 in L.A. with Bobby Knight running the team, bracketing the 1980 Moscow boycott.

And after the Soviets upset John Thompson’s 1988 squad in Seoul – this time without benefit of second or third chances – Olympic basketball was opened to professionals in 1992 in Barcelona. That year, the Dream Team beat everyone by an average of 44 points a game.

In the pro era, the U.S. has won seven of eight possible gold medals. Russia has medaled once, a bronze in 2012.

Silver? No thanks.

jalexander@scng.com