Addressing a packed room of fellow immigrants, Isabel Coronel recalled how as a retired farm worker, she never used to seek medical help because she didn’t have health insurance.

Right after her talk, Coronel headed to a doctor’s appointment.

Thanks to a law that took effect May 1, residents like Coronel — who are older than 50 and living in the country without legal immigration status — can now qualify for full Medi-Cal services. It’s part of a Medi-Cal expansion that began in 2016 for immigrant children, and by 2024, it will cover all low-income adults and children in the state, regardless of immigration status.

On Jan. 1, 2024, California will become the first state in the nation to offer state-subsidized health insurance to all low-income immigrants residing in the country regardless of their status.

This summer, Gov. Gavin Newsom announced a budget deal that will expand the health insurance program to the last group of undocumented adults not currently covered: those between the ages of 26 and 49. That’s more than 700,000 residents in California who don’t qualify now because of their immigration status.

“This is a historic moment for California, reaching a goal that was nearly impossible just seven years ago,” Sen. María Elena Durazo, D-Los Angeles, said following the announcement of the state budget agreement. Health care, she said, “is a human right.”

It’s the last piece of a goal that immigrant-rights supporters have been pushing for years.

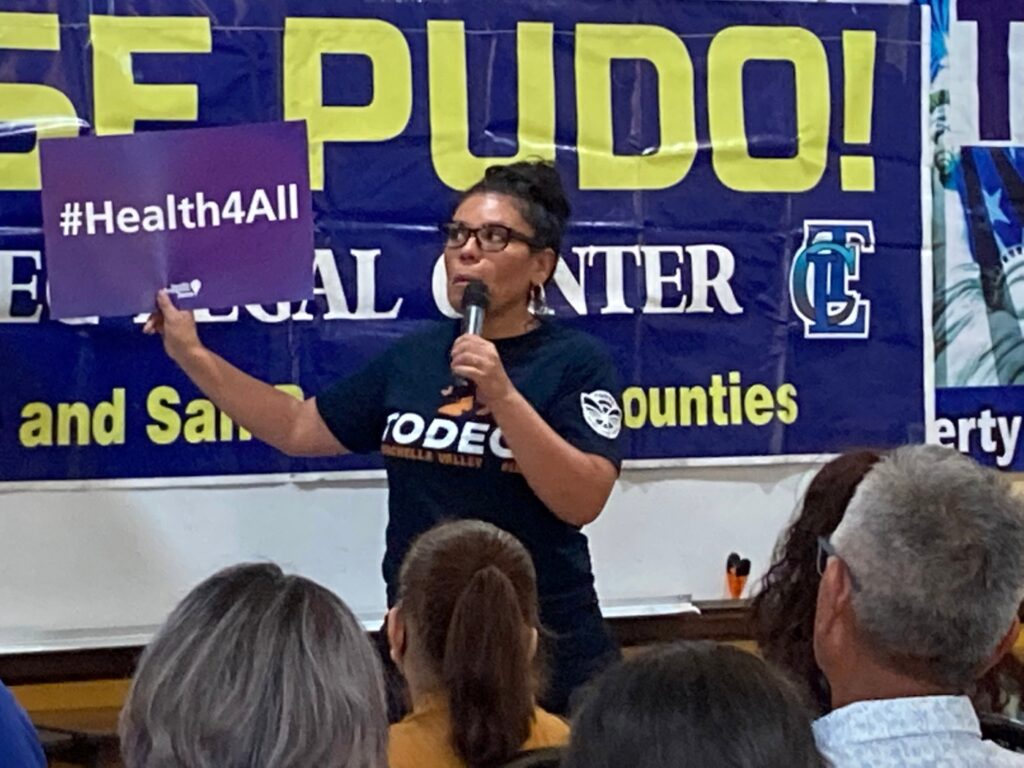

“We are who we are as a state because of the contributions of immigrants. We need to protect and defend and really value our workers who should have access to all the safety net programs, including health care,” said Luz Gallegos, executive director of the immigrant-rights advocacy TODEC Legal Center in Riverside County.

TODEC recently held one in a series of workshops to educate residents about the changes and help them register for Medi-Cal, the state’s version of the federal Medicaid health care program for people with limited income.

That’s where Coronel, a 77-year-old Perris resident and retired farm worker, shared her story.

Isabel Coronel, 77. outside the TODEC Legal Center in Perris, CA. on Aug. 12, 2022. (Photo by Roxana Kopetman, Orange County Register/SCNG)

“I didn’t go to doctors,” Coronel said during an interview this week. “Many times, we just relied on homemade cures.”

Then, Coronel got COVID-19 in the early stage of the pandemic and became seriously ill. So did her daughter. Farm workers she knew died, unable to get help.

In the summer of 2021, Coronel joined Gallegos and other advocates in a meeting with Newsom where they pleaded their case.

“She talked about community members, our workforce, giving their life to California,” Gallegos said.

At the time, advocates were pushing state officials to cover older residents, but also expand coverage to everyone, regardless of age or immigration status.

What pushed the needle, after years of advocacy, was the pandemic, which hit low-income workers the hardest, Gallegos said.

“It really took COVID for people’s moral consciousness to kick in. If it wasn’t for COVID, we wouldn’t be where we’re at,” Gallegos said.

Expanding Medi-Cal to eligible undocumented immigrants is expected to cost the state $2.2 billion on an ongoing basis, according to an estimate by California’s Legislative Analyst’s Office.

The Department of Health Care Services estimates that more than 1.1 million residents will be eligible to enroll by 2024: 119,000 children; 105,000 19 to 25-year-olds; 707,000 adults younger than 50; and 238,000 adults 50 or older, a spokesman said. The California Legislative Analyst’s Office estimates the number of 26 to 49-year-olds could increase to 764,000 residents.

It’s estimated that California has some 2.5 million unauthorized immigrants. People who qualify for Medi-Cal include disabled residents, pregnant women, and immigrants with refugee status. Residents whose income is at 138% of the federal poverty level also qualify — an income of $38,295 for a family of four.

Unauthorized immigrants already qualified for emergency Medi-Cal services, and those were automatically transferred into the full range of services offered under Medi-Cal when the new laws kicked in. In 2016, it began with coverage for children up to the age of 18. That was later expanded to young adults up to the age of 26. And beginning May 1, the low-cost and free coverage was offered to people older than 50.

Jon Coupal, president of the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association, previously told the Associated Press he was concerned the free health care move would make California “a magnet for those who are not legally authorized to enter the country.”

RELATED: Older undocumented immigrants to get Medi-Cal health care in California

Not everyone jumped at the chance to sign up.

Some people said they fear that information they share will be forwarded to immigration authorities. Others said they fear if they tap such resources it could be used against them if they seek a legal permanent residency card and eventually U.S. citizenship.

Marivel Castaneda, with Riverside County’s Department of Public Social Services, has this message: “Don’t be afraid. All your information is confidential.”

As for being considered a “public charge” if applying for health care help, earlier this year, the Biden administration moved away from regulations that counted Medicaid enrollment against applicants seeking legal residency.

For Coronel — known in the community as “La Coronela” — the new law expanded to those over the age of 50 has already made a tremendous difference.

“It’s helped me a lot,” she said. “I’ve been suffering for so long but I didn’t see any doctors.”

For the first time, she also started seeing a dentist and an optometrist, in addition to regular doctor visits for various ailments.

Her next appointment is in October.