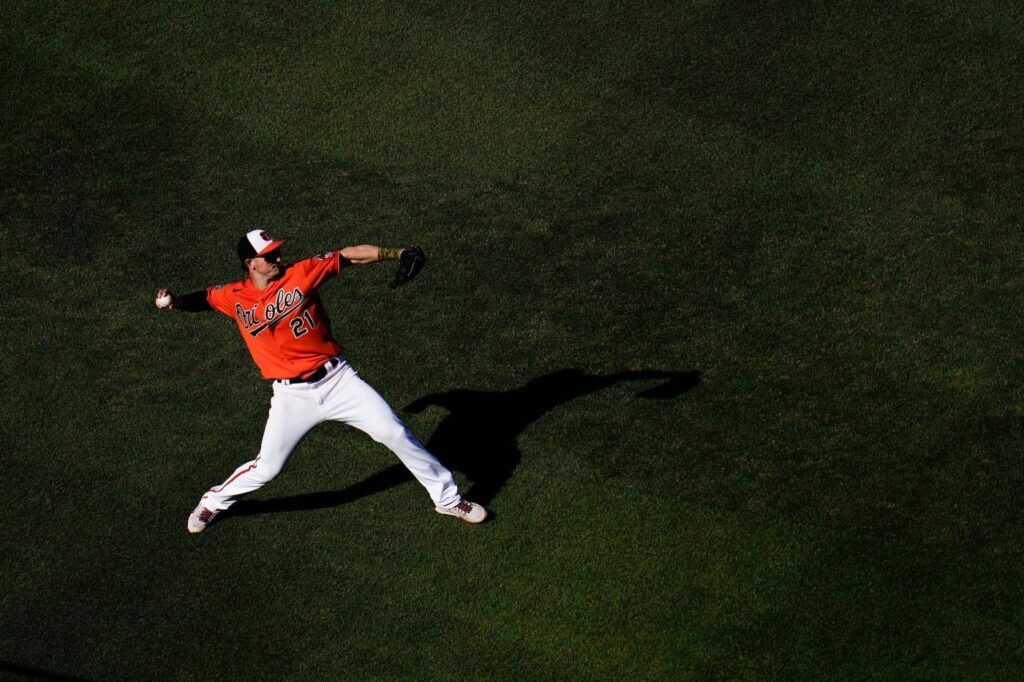

There’s no way to precisely predict the carom of the ball off the wall, or the angle Austin Hays will find his body when he picks his head up in the outfield to fire toward a base. Still, his pregame routine sets him up to be as prepared as he can be for the unknown.

It consists of four to five throws. There’s one coming in on the ball, firing a toss through the air to second base. There’s another backhand stop, forcing him to run to his right before planting and throwing. Another is a spin, with him ranging left and twirling.

And then there’s the final effort, the one that’s most closely aligned with what Hays has made a habit of doing in games. After first base coach Anthony Sanders hits a ball toward the wall, Hays will chase it down, gather in whatever bounce might come and then hurl it toward the infield.

“It’s something that’s really short, quick, easy to do. It’s not very exhausting,” Hays said. “But those same throws always come up in the game.”

That’s the art of perfecting the outfield assist, through the lens of Hays. The Orioles outfielder has four outfield assists this season, with two of them registering at 100 mph out of his hand. He’s making a name for himself as a fielder not worth running on — third base coaches throw the stop sign up routinely now, not risking an out at the plate by the arm of Hays.

“It’s not just the arm strength, it’s the accuracy, being able to put the ball on the bag, with carry, at 100 mph,” manager Brandon Hyde said. “You just don’t see that around the league.”

Long before the flashy plays around major league ballparks, Hays made a habit of working on his arm strength in early high school. The earliest outfield assist that sticks out in his head came during his sophomore year at Spruce Creek, a playoff game against Hagerty, another Florida high school power.

At that point, Hays was playing right field. And on a ball hit into right-center, he dove to prevent it from reaching the wall, then flung a strike to second to nab the runner. That play, he felt, came as a result of all the effort he put into throwing each day.

“I would always throw the most of anyone on the team,” Hays said. “Everybody always told me I threw too much, but — knock on wood — I’ve had less arm problems than every other person who told me I threw too much.”

Beginning as a 13-year-old, Hays began to long toss five or six times a week. He still warms up by long tossing before Orioles games, although he limits himself to about 250 feet rather than going all the way back to the wall. That, plus his pregame ritual of four or five specific throws, helps him hold a 1.8 ARM rating — a FanGraphs measurement of how many runs Hays has saved above average based on his arm strength.

“Building a good foundation of long tossing and throwing every single day when I was younger just led right into pro ball, being able to throw every day,” Hays said. “Guys who didn’t throw as much, in pro ball, now you’re playing every single day, their arms were getting tired, sore, tight. I’d already been throwing every day.”

Hays remembers just about every outfield assist of his major league career — all 17. They mean more to him than any home run does, because the frequency around the league is so much lower. So Hays was able to pick a favorite from the bunch.

When Minnesota Twins catcher Gary Sanchez squeezed a double inside the left field line May 5, Hays charged down the ball, scooped it off a deflection from the side wall and came up throwing. His one-hopper to catcher Robinson Chirinos beat Max Kepler to the plate.

“It was a super unorthodox play,” Hays said. “It was kind of hooked down the line, I was throwing it across the runner, and it was right on the money. That’s probably my favorite one just because I had never thrown a ball to home from that spot.”

It’s one of things Hays can’t simulate, even as he takes a few practice throws before each game. When the ball is hit, sometimes it just comes down to an arm Hays has been building up since early high school. And more times than not, he’s shown that unique combination of strength and accuracy to leave runners shaking their heads and umpires signaling another out.

()