The wisest thing to do with an exceptional increase in the state’s tax revenues is to save it for the time when there is an exceptional decrease in those revenues. There is even Biblical precedent for this common sense approach: Joseph got to be Pharaoh’s chief minister by storing up seven years’ grain surpluses to cover the seven years’ famine that followed.

The complex system of California’s state finance, however, impedes applying this wisdom. In 1979, California voters adopted the Gann Limit — named for Paul Gann, the co-author of the previous year’s limits on property tax Proposition 13. The purpose was well intentioned, to rein in the natural tendency of all governments to grow. Expenditures in California were set at their 1978 levels, adjusted only for population growth and the growth of personal income. When state tax revenue grew faster, the difference had to go back to the people. In 1990, another initiative refined the Gann Limit, requiring the excess to go 50% to California’s public schools and 50% to taxpayers. Alternatively, the surplus could be spent on capital projects, defined as having a useful life of more than 10 years.

What was not permitted was to send the extra money into a state rainy-day fund. That would count as an expenditure, and limiting expenditures was the whole purpose of the Gann Limit. However, some expenditures are profligate, and some are wise. California voters expressed support for fiscal prudence in a different initiative approved by in 2014, requiring 1.5% of the state’s general fund, and a varying percentage of the state’s volatile capital gains revenue, to go every year into a reserve for fiscal crises.

Regrettably, that initiative did not adjust the Gann Limit. So, Californians’ desire to curb profligate spending now impedes our instinct for prudent saving anticipating hard times. Hard times are coming. The remarkable growth of the stock market values, coupled with renewed formation of new companies with the attendant reward of initial investors, has inflated California’s capital gains revenues over the last year.

The easing of the pandemic has also contributed to that effect, but that surge has now run its course. Further, the stock market is signaling a serious downturn. The Standard & Poor’s 500 index reached its historic peak at 4,463 in March. That was almost a doubling of its value from 2020. Since March, however, that index has dropped almost 9% in less than two months. No economist is predicting a rise; discussion, rather, has focused on whether the Federal Reserve can bring down inflation without inducing a recession.

A “soft landing” is what is being pursued — but that means a “landing” nonetheless and with it an evaporation of much capital gains tax revenue for California.

Related Articles

Newsom budget at last recognizes one housing reality

As drought persists, water rights on agenda

Memorial Day: Political Cartoons

Contrary to the Founders’ intentions, guns run the American game

The law and the Gann refunds

In California’s most recent state budget, more than 12% of the entire general fund account came from capital gains taxes (24.5 out of 193.8 billion dollars). California could lose almost all of that in a market downturn. In the collapse of the housing bubble in 2009, California took in only $3 billion in capital gains taxes. A return to that level would necessitate a massive cut in California’s state expenditure, including for Medi-Cal and low-income housing assistance, whose needs would grow as unemployment rose in a downturn.

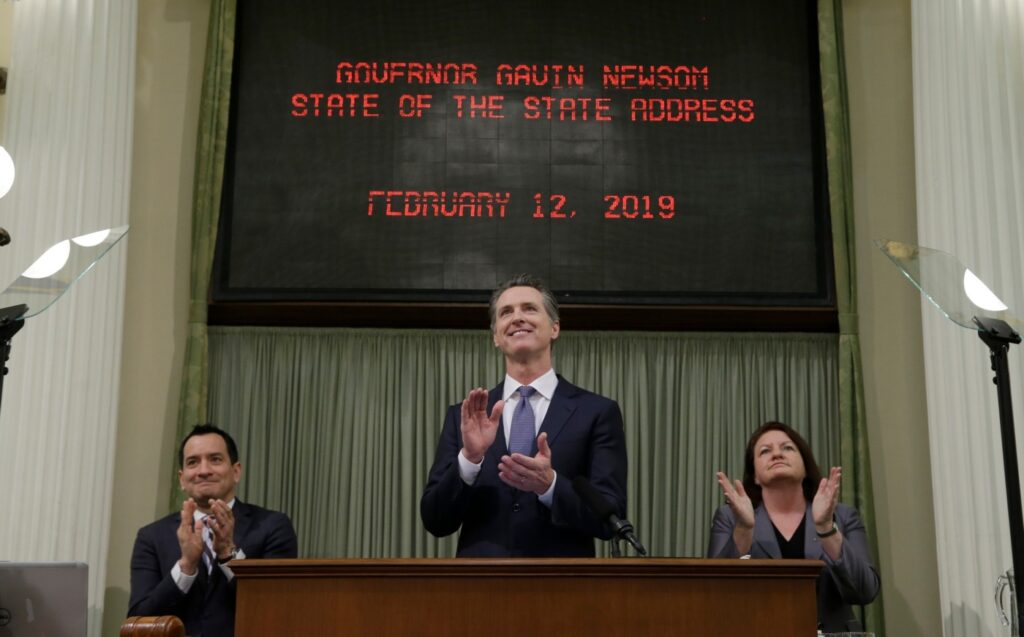

The Gann Limit needs to be changed, so that the surplus could be put entirely into California’s rainy-day fund. Until that change happens, Gov. Newsom has limited options. He has proposed refunding half the surplus to taxpayers, applying a rather elastic concept of what qualifies as a tax rebate (e.g., sending $400 per car to every Californian auto owner). The other half has to go to schools (even though our school-age population is declining). A better choice would direct the surplus 100% to infrastructure. We need dams, freeways and expanded port facilities, and construction work on such projects would cushion employment drops during the coming “soft landing.”

Tom Campbell was California’s director of finance under Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. He is a professor of economics and of law at Chapman University. He served five terms in Congress, including on the Joint Economic Committee. He left the Republican Party in 2016 and is in the process of forming a new party in California, the Common Sense Party.