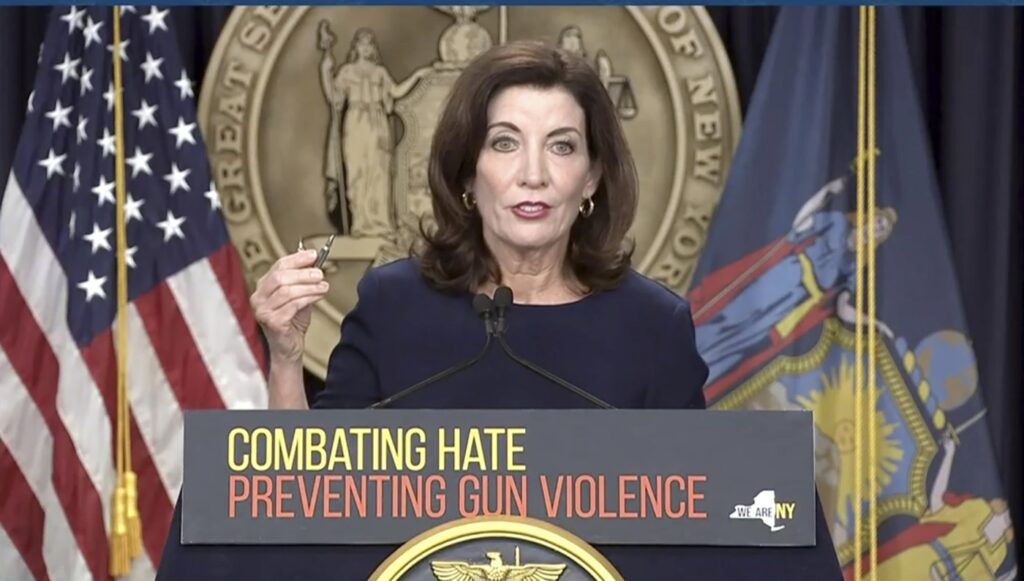

When politicians echo Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’ famous observation about “shouting ‘fire’ in a crowded theater,” it typically means they are trying to justify unconstitutional speech restrictions. So it was with New York Gov. Kathy Hochul’s comments after the racist mass shooting that killed 10 people at a Buffalo grocery store on Saturday.

Hochul was responding to questions from “Meet the Press” host Chuck Todd, who during Sunday’s show condemned “a permissive culture on the internet” that allows “right-wing extremism” and “white supremacy” to run rampant. Given the role that such views played in Saturday’s horrifying attack, Todd asked Hochul, shouldn’t “internet companies” be “held responsible for the easy spread of this propaganda”?

Todd noted with dismay that critics of that proposition tend to cite “freedom of speech or things like this.” Hochul shared his impatience with such objections.

“I’ll protect the First Amendment any day of the week,” the governor said. “But you don’t protect hate speech. You don’t protect incendiary speech. You’re not allowed to scream ‘fire’ in a crowded theater. There are limitations on speech.”

Hochul is right that the Supreme Court has recognized exceptions to the freedom of speech guaranteed by the First Amendment. She is wrong in thinking that “hate speech” is one of them.

As First Amendment scholar David Hudson notes, that provision “makes no general exception for offensive, repugnant, or hateful expression.” To the contrary, the Supreme Court repeatedly has held that bigoted and outrageously inflammatory speech, including the sort that influenced the Buffalo shooter, is constitutionally protected.

Hochul, who has a law degree, should know that. But her allusion to the analogy that Holmes drew in the 1919 case Schenck v. United States tells you how little regard she actually has for the freedoms she claims she is prepared to defend “any day of the week.”

In that decision, the court unanimously upheld the Espionage Act convictions of two Socialist Party leaders, Charles Schenck and Elizabeth Baer, who had sent recently drafted soldiers “printed circulars” arguing that conscription violated the 13th Amendment’s ban on involuntary servitude. While that argument might be tolerable in ordinary times, the Court said, it posed “a clear and present danger” during World War I and therefore was properly treated as a crime.

“The character of every act depends upon the circumstances in which it is done,” Holmes wrote. “The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic.”

A week later, in two more unanimous opinions by Holmes, the court applied the same logic to uphold the Espionage Act convictions of Socialist presidential candidate Eugene Debs and newspaper publisher Jacob Frohwerk. As the court saw it, the First Amendment did not protect a speech urging resistance to the draft or articles criticizing U.S. involvement in World War I.

Within six years, however, the court began to retreat from the “clear and present danger” test. The current standard for punishing allegedly crime-promoting speech, laid out in the 1969 case Brandenburg v. Ohio, asks whether it is both intended to incite “imminent lawless action” and “likely” to do so.

Related Articles

One-party-rule has made California unaffordable for hardworking families

Armenia is in need of America’s help right now

Border control: Political Cartoons

Progressives vie with ‘mod squad’ for power in California Legislature

Online hate: Political Cartoons

Under that test, it is clear that promoting racist and antisemitic ideas such as “replacement theory,” which posits that Jews are conspiring to make whites a minority in the United States, is constitutionally protected. Yet Hochul seems to prefer the repudiated jurisprudence that allowed the government to imprison Schenk, Baer, Debs and Frohwerk.

Hochul’s invocation of Holmes’ analogy makes it clear that she is not just talking about voluntary moderation by social media companies. “I want to silence those voices now,” she said at a Buffalo church on Sunday.

If “the social media platforms that allow this hatred to ferment” fail to suppress it, Hochul said, “I will use every bit of the power I have as your governor to protect you.” Fortunately, Hochul does not have as much power as she thinks.

Jacob Sullum is a senior editor at Reason magazine. Follow him on Twitter: @JacobSullum.