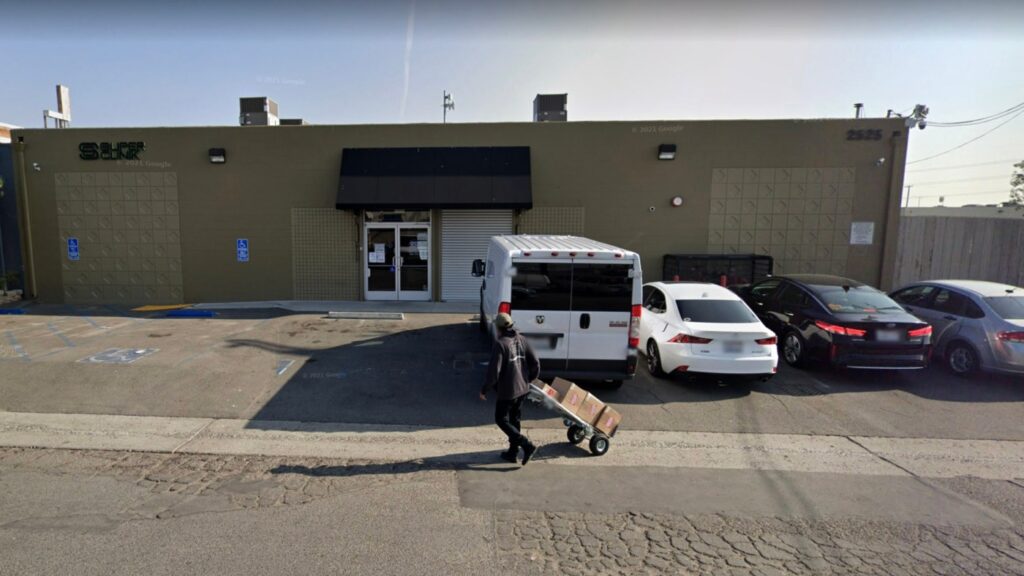

Two California Highway Patrol vehicles and a half dozen unmarked vehicles blocked off the parking lot of Super Clinik, a licensed cannabis store in Santa Ana, just after the shop opened at 8 a.m. on the morning of March 18.

With an agent from the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration looking on, several CHP officers went inside, counted out a couple six-inch high stacks of cash and took them from the Birch Street store, according to witness reports and photos from the scene.

Super Clinik owners didn’t respond to multiple requests to speak for this story, while state tax officials said privacy laws prevent them from discussing specific cases. But experts said the operation at the Santa Ana shop had all the hallmarks of a “till tap” civil warrant, which the tax agency uses to seize cash from businesses that haven’t paid sales tax bills despite escalated warnings.

This is the second such operation reported at a longstanding, licensed cannabis shop in Southern California in the past month. In early March, a shop called TLC in Boyle Heights, owned by the well-known industry veterans Jungle Boys, also got raided by the CDTFA and CHP. The business posted video from the incident on its Instagram page, saying officers came in with guns drawn and took more than $100,000 from their cash registers after they paid $18 million in taxes in 2021.

“That’s triggering to all of us because this is what used to happen regularly,” said Dana Cisneros, an attorney who’s worked with cannabis businesses for 15 years.

For decades, law enforcement raided pot shops in California, arresting people on site and seizing goods as businesses operated in the gray space created by loose medical marijuana laws. But with recreational consumption of cannabis legal in California since 2016, and the state giving members of the fledgling industry some leeway, raids of licensed shops have been rare in recent years.

Now, the recent reports of tax raids have industry insiders wondering if state authorities are entering a tougher phase of enforcement when it comes to dealing with licensed operators.

Pressure points

Such an escalation was inevitable on the one hand, as the industry matured. But there’s also evidence that even as most cannabis businesses are paying their tax bills on time, the industry is a bit less likely than others to do so.

The state reports that 99% of all businesses in California pay their sales tax on time each quarter, but the pay-on-time rate for the cannabis industry is about 90%. And with nearly $309 million in tax revenue collected from cannabis businesses in the final quarter of 2021, and nearly $3.5 billion raised since taxes took effect in January 2018, that default rate means cannabis businesses owed the state more than $11 million in past-due taxes at the end of last year.

Add to that another factor — some licensed cannabis operators continue to do work in the unlicensed side of the industry.

Rob Taft, owner of 420 Central in Santa Ana, said he’s long predicted that California and other governments would eventually use tax enforcement to target potential bad actors in the cannabis industry, the way gangster Al Capone was ultimately brought down for tax evasion. In that case, rather than giving businesses leeway, Taft and others suggest the state might have been giving cannabis operators just enough rope to hang themselves.

“We’ve pretty much pounded into (our clients) that the scariest boogeyman in the scope of enforcement is the tax man,” said Hilary Bricken, a cannabis industry attorney in Los Angeles.

Taft and others in the industry said they don’t support anyone not paying their taxes. But they also say there couldn’t be a worse time for the state to start targeting licensed businesses in such a forceful way.

Just 26% of California’s cannabis businesses are turning a profit, according to a January report from the Portland-based data firm Whitney Economics. That’s well below the national average of 42%. Among the 17% of operators who are only breaking even, and the 56% who are losing money, some anecdotally are talking about either leaving California or going back to the illicit market where many of them got their start.

“They’re choking us out,” Taft said.

Where is the protection?

One problem is the persistent existence of the underground cannabis market. It’s tough for licensed operators to start up in California, while it’s not hard for illegal operators to stay in business. As a result, most experts believe the underground cannabis market is about twice as big as the licensed business in California.

That makes tax raids on licensed businesses — by state officials who, in theory, could be stamping out illegal operators — particularly frustrating, Cisneros said.

“I’m not saying anybody should not pay their taxes,” she said. “But where’s the enforcement to protect people who are complying with the law, or at least trying?”

The state’s Department of Cannabis Control has been reluctant in the early years of legalization to make aggressive moves even against unlicensed cannabis businesses. Leaders said they wanted to use a “carrot” rather than a “stick” approach in hopes of getting more illicit operators to move into the regulated market.

While some licensed operators have been frustrated with that approach, Bricken said she’s concerned about the chilling effect that aggressive CDTFA raids will have on efforts to convert more businesses.

“People in the illegal market will see this and it’s another reason to say, ‘Why would I ever transition?’”

The second main factor that licensed businesses say is throttling the industry is the same thing sparking the recent raids: taxes.

Sellers have been raising flags about a need for relief from industry taxes that can easily hit rates of 45%, driving up the cost consumers pay for safe, regulated products and creating a window for unlicensed operators to grab market share. In Sacramento, some lawmakers are pushing to ease cannabis taxes, but most in the industry aren’t confident that they’ll pass.

So in recent months some licensed operators have threatened to withhold their tax payments from the state and put that money into escrow accounts as a way to prove a point. But there’s no evidence that any licensed businesses have followed through on that threat, or that either of the recent CDTFA’s raids had any connection to such an effort.

In the case of Jungle Boys, the company reports it’s been appealing $60,000 in penalties and interest that CDTFA says it owes on a $130,000 tax bill. While that appeal was still pending, the company says the agency came and collected more than what they reportedly owed.

“CDTFA is coming out swinging,” Bricken said. “And they’re the perfect agency to do it because they’re nearly untouchable.”

When asked about till tap operations, agency spokeswoman Tamma Adamek pointed to a document that explains such civil warrants (which typically are executed with help from either the CHP or local police) are issued only after verbal and written collection requests have proven unsuccessful.

The policy states that CDTFA also can collect funds beyond the overdue tax fees to cover the cost of executing the till tap.

That’s why Bricken said she always advises her clients to pay whatever taxes the state says they owe up front, and then appeal to get back any funds that are rightfully theirs.

When businesses get upside down with CDTFA, she said she expects the agency will share that information with the IRS, which can invite federal attention. Reports of raids also can harm relationships with customers, vendors and financers, who already are hard to come by in an industry that’s still considered high risk.

“They are looking to make examples of people,” Bricken said. “And the bigger the target, the more influential the message.”

The CDTFA is not specifically targeting cannabis businesses, Adamek said. But till taps, she explained, do work best with cash-heavy businesses such as bars, gas stations and cannabis stores. While other industries are cash-heavy for different reasons, cannabis operators rely on cash because their product is illegal under federal law and they can struggle to get access to federally-regulated banks.

Rather than risk such drastic action by refusing to pay tax bills, Taft said he’s encouraging licensed businesses to be “good operators” and to protest California’s high cannabis taxes by joining organized efforts to bring rates down. He’s part of a group of licensed business owners that recently filed a petition, for example, asking Santa Ana to lower its local cannabis tax from 8% to 4%.

“The government is not going to do it for us,” he said. “We have to be the ones pushing.”