John Kenney is one of six brothers.

In 2019, when his brother Tom, a firefighter who spent a week at Ground Zero in 2001, was dying of cancer, Kenney went to visit him one last time. As they were talking, a car pulled up carrying the other four brothers. When Kenney noted their arrival, his brother let his head and body slump as if he had just died. “Tell them they’re too late,” Tom said with a sly grin.

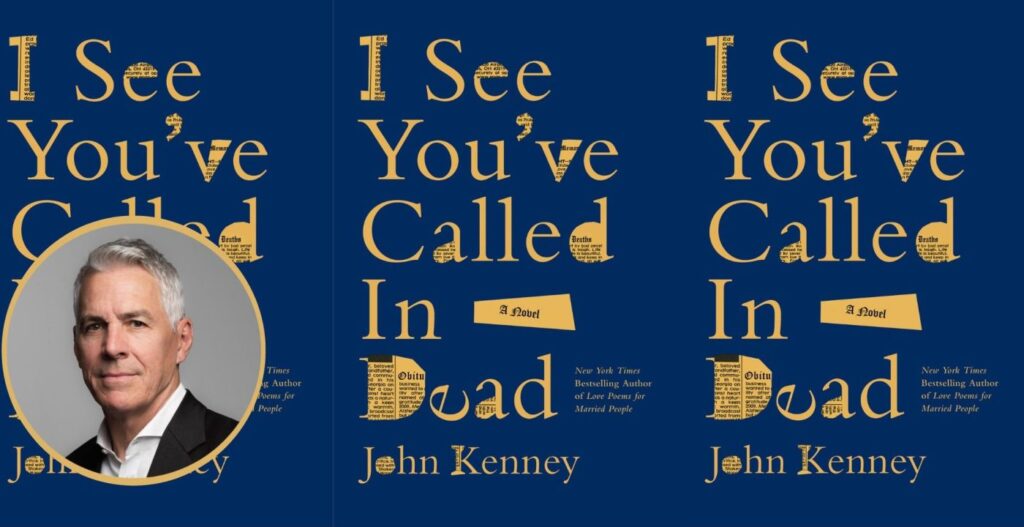

From that moment, Kenney’s latest novel, “I See You’ve Called in Dead” was born.

SEE ALSO: Like books? Get our free Book Pages newsletter about bestsellers, authors and more

“My brother’s death was the catalyst,” Kenny says. “I was laughing but I was also so stunned and in awe that someone could have the humor and courage to do that in this moment. I thought, ‘I want to write a funny book about death.’ Which is not a pitch most publishers want to hear.”

The novel’s protagonist is Bud Stanley a news service obituary writer struggling with wounds old (his mother’s death when he was a boy; this is autobiographical) and new (his wife left him two years ago for a better-looking, more successful guy; Kenney, 62, is happily married with two kids).

Early on a blind date goes horribly awry – the woman is 45 minutes late, then shows up to apologize and say she just got back together with her ex… who accompanied her to the bar. More depressed than usual, Bud goes home, gets drunk and writes his own obituary.

“Bud Stanley, the first man to perform open-heart surgery on himself…” it opened, later claiming he was the Dalai Lama’s “younger twin brother,” the founder of Tears for Fears who “refused to take credit for the songs he wrote,” and a soft-core porn script doctor “fired for insisting on more plot and less nudity.”

Caught up in the moment, Bud posts the obit on his company’s website. His death makes waves at the office, where he’s promptly suspended. Free falling, he ends up going with his best friend Tim and a woman he meets named Clara to a series of wakes and funerals, a “device,” Kenney says, for exploring the book’s real ideas – how we struggle with death but also how we often avoid fully living.

This interview, at a cafe in Brooklyn near where most of the book is set, has been edited for length and clarity.

Q. After your brother’s death, did you know what you wanted to say about death and dying?

Every day people die and we all walk around thinking we’re immortal. It’s certainly true of me. It’s very difficult to sit with the notion we are going to die.

We’ve all been to funerals and wakes and sit shiva and yet I don’t know how to think about it. I have no vocabulary for death. I go to wakes and feel incredibly awkward. I don’t know what to say. But I do know that it’s not good to say ‘The receiving line was really long and my legs are tired.’”

So I just wanted to ask questions. I don’t know anything.

Q. Did you learn anything?

I would love to say I’m some sage now and understand things about death but death still scares me and confuses me. Death makes us ask, “How am I supposed to live?”

The pain doesn’t go away but you have to live. And with the profound emotion there can be a little window into beauty.

Another brother of mine died seven weeks ago.

Q. I’m so sorry.

His death was weirdly beautiful. He was diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumor and knew he had about a year to live. He was in no pain. We talked almost every day and visited and had some fantastic times together. He had a sense of the wonder and joy of life.

It was very strange because I was asked to write his obituary. But even though I’d just spent three years writing this book I froze up completely. How do you sum up someone’s life and bring them back to life with your words?

Q. Bud talks about how hard it is to convey tragedy in words. You do it by focusing on something beautiful during a wake for a woman and her young son who died in a car crash. You linger on small pleasures for parents, who think they have all the time and tomorrows we expect: “Talking of the day, of lunch, of coloring, of nonsense, the parent listening, half listening, not listening… [She puts him] in his car seat, buckles him in, burying her face in his neck, a little kiss.”

Why was this so crucial to the book?

The book was largely done and I was walking one afternoon and was struck that the wakes and funerals were all for older people. I thought, ‘That’s kind of cheap. Life’s a lot crueler than that.’ I was taking the easy way out. I told my editor, who’s a young mother and she said, “I’m not sure I’m comfortable with that.” But then she read it and said, “You have to include it.”

It would have been disingenuous to gloss over how brutal life can be. We’d had a couple of wakes and funerals that were a little funny and I wanted one to grab the reader and say, “This is serious business. Respect this.”

Q. The plot device is all about death but the book is ultimately about figuring out how to live.

There’s an order of nuns that practice the notion of memento mori, which can translate as “Remember that you will die.” The idea is that this makes life beautiful. That’s counterintuitive to my mind but I find it interesting.

So the point of the book isn’t the wakes and funerals, it’s that this character is just flitting through life and is not awake. It’s about male friendship. I once had a ton of friends and acquaintances and I have very few friends now. And I think friendships are important.

Q. Bud talks about having to stay in the pain to make it go away. Does it go away or just become manageable?

I tried running from pain, pushing it out of my mind, drinking it away, eating it away, it’s always there. If you sit with it and try to understand it you can learn to live with it – it’s with you every day but you can get to where it doesn’t cripple your life.

Q. The book is funny, but it’s more weighty than other novels, not because of the deaths but because depression haunts or has haunted Bud, Tim and Clara.

I have struggled mightily with depression at different points and I think it’s still a subject that makes people uncomfortable. It’s hard to talk about. Getting through the day with sadness is an interesting topic. It’s hard to be a person. I’m not sure I could get through the day without making fun of the pain and myself.

But I hope people laugh. I like troubled, wounded people who are trying to get through the day, and there’s awkwardness and hilarity there. I really hope to make people laugh but I also hope to make them feel. There’s a lovely symbiosis between the two.

Q. You also largely subvert our expectations about learning life lessons and romance.

This is not a plot-driven book, it’s a fairly quiet story without a major revelation at the end. I wanted something subtle because that’s what happens in life. When the eye doctor is testing you and they say, “Better or worse,” for each small shift in acuity. That’s the day-to-day for most of us. We always have the chance to change a little bit, whether it’s a perspective or habit or the thoughts in our head that seem so set in those deep grooves with a narrative. That’s what it’s about.

Related Articles

Novelist Percival Everett and playwright Branden Jacobs-Jenkins among Pulitzer winners in the arts

How classic detective mysteries inspired Louise Hegarty’s ‘Fair Play’

How ‘Good Movies as Old Books’ turns film classics into vintage paperback designs

‘Jack Kirby: Heroes and Humanity’ celebrates a comic book legend at the Skirball

This week’s bestsellers at Southern California’s independent bookstores