All Melissa Ludtke wanted to do was report and write about baseball. She made history instead.

Ludtke, then a 26-year-old reporter-researcher for Sports Illustrated magazine, was banned from both teams’ clubhouses during the 1977 Yankees-Dodgers World Series games in New York by order of Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, even after the teams themselves had agreed to let her in. And in the aftermath, she signed on as plaintiff in a lawsuit against Kuhn and Major League Baseball that ultimately opened those clubhouse doors to all, regardless of gender, based on the due process and equal protection clauses of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution.

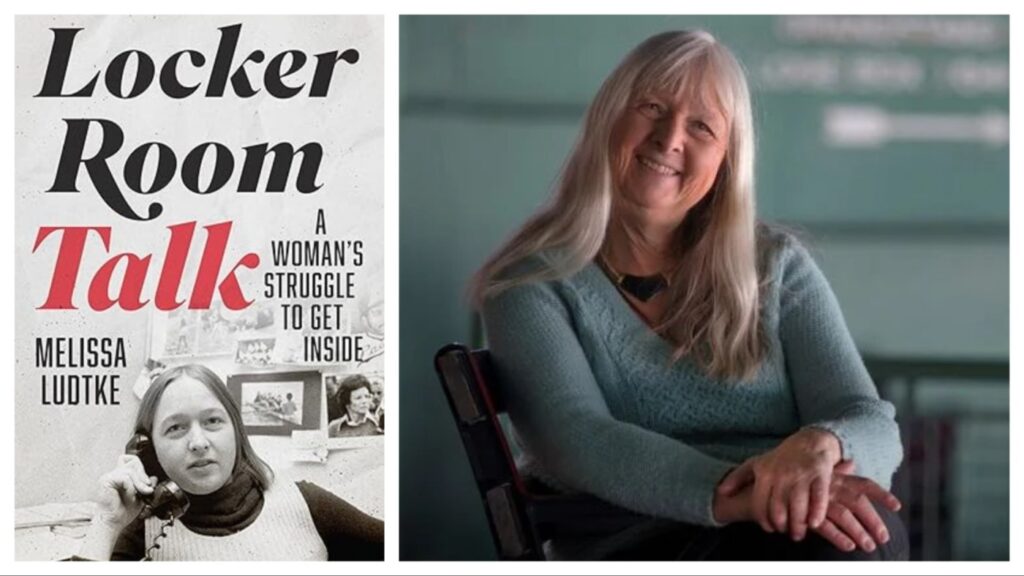

It has been 46 years since that case was decided by federal judge Constance Baker Motley, a decision that over the years has made sports journalism not only more equal but better. But only now has Ludtke put the narrative behind those events between covers, in “Locker Room Talk: A Woman’s Struggle To Get Inside” (Rutgers University Press, 2024).

The first question I asked Ludtke when we talked this past week over Zoom was why it took her until now to write this story.

“There was no strategic thinking behind it,” she said, adding that she wasn’t planning for a particular moment because she “didn’t know how long it would take me to write it.” The legal research needed to help reconstruct the details of the trial had to have been time-intensive.

As it turns out, this is the right time. Women’s sports are thriving as never before and females have not only become ubiquitous in sports media but have planted the flag in sports organizations themselves, rising above the misogyny that way too often pokes its head out of the ground.

Also, younger generations seem to be taking more of an interest in the steps their elders took to help get society where it is now.

“There was a long period where no one was interested” in that court case, Ludtke said. “No one approached me. It wasn’t something that I put out in the world when I met people that I had been involved in this suit.

“It wasn’t until maybe 10, 15 years ago that I started getting calls, first of all from high school teachers,” she added. “I’d get emails from them and then we’d do things over Skype because students in their classes were discovering the case through Google and through the rest in terms of National History Day projects they were doing.

“What’s happened in the last few years is that a number of college professors now get in touch with me, usually again through email, or they find my phone number to call me, but they want me now to Zoom into their classes or come by and talk with their classes.”

Just imagine, then, the idea that you’re not only still alive and thriving but now people are thinking of your past as history to be studied.

“It really was first this notion that, wow, I’m still alive. And yet people are considering what I did as history,” she said. “So this idea of being living history made me think about whether I had a story that was my responsibility, you know, or obligation or, you know, commitment, or gift to my daughter (now 28) and to her generation of telling this story.”

Who knows? Maybe “Locker Room Talk” will pop up on some college courses’ reading lists, be it Journalism or Women’s Studies classes.

The issues here were two-pronged.

The main argument, the one that Ludtke and her attorney argued before Judge Motley, was that by not having the same access as other reporters to players’ immediate postgame reactions and emotions because of her gender, she was at an unfair disadvantage. The separate-but-equal concept of bringing players out to a hallway to be interviewed – after they had talked to the male reporters and in all likelihood weren’t crazy about having to talk again – was in no way satisfactory, much less anything resembling equal.

That argument resonated with Judge Motley, whose background was as an attorney battling Jim Crow discrimination.

The discourse, of course, was muddied because the general tenor of conversation – mainly among those giving this matter no more than a cursory thought – was that she was just trying to get into the clubhouse to stare at naked men.

The point of Kuhn’s ban, as he was quoted, was to protect the “sexual privacy” of players. And never mind that in the Yankee Stadium clubhouse at that time, all but two of the rooms in the home clubhouse complex – including the showers, toilets, training rooms and the like – were off limits to reporters anyway.

It is still that way in virtually all clubhouses and locker rooms at all levels of sport. In fact, reporters and camera crews now customarily wait for players to get dressed before even approaching them for postgame comments.

But those tropes predominated then, the late ’70s, when columnists – predominantly men – poked fun at the woman who dared attempt to enter the locker room.

“It’s in the court of public opinion that I lost,” Ludtke says now. “The fact that I won in a court of law is what’s held up and what has mattered, particularly for women who have wanted to get into this business in the intervening decades and worked their way up into positions that, you know, back in the ’70s, I don’t think any of us would have (anticipated).”

And that gets to the heart of another reason why Ludtke wrote this book, which gets deep into the specifics of the trial:

Related Articles

Alexander: Golden at-bat? It would only tarnish baseball

Alexander: Trojans’ season filled with valuable lessons

Alexander: Kings goalie Erik Portillo can be proud after dazzling NHL debut

Alexander: Dodgers’ signing of Blake Snell creates the traditional uproar

Alexander: Rams-Eagles was Saquon Barkley’s show

“Despite all of the coverage my case got in (1978), particularly from the New York press, not one reporter showed up at that hearing,” she said. “Not one. They had no interest in that. … Sex sold, and equal rights didn’t. And they weren’t interested in it, and so they consequently felt they had nothing to learn by going.”

When Ludtke talked of how she grew up loving sports, particularly baseball, and how that was handed down from her mother, I thought of another woman ahead of her time who’d had a similar experience: Roz Wyman, the late L.A. city councilwoman who helped lead the effort to get the Dodgers here from Brooklyn in the 1950s. She, too, inherited a love of baseball from her mother.

In those generations, it might have seemed odd. Today it isn’t. I’d say that’s progress.

jalexander@scng.com