How is the housing market doing?

The answer depends on whom you ask, says Lawrence Yun, chief economist for the National Association of Realtors.

“Some people will say it is terrible,” he told real estate writers at a recent conference. “(Others) will say this is one of the greatest things that has ever happened.”

“So, we have a really strange real estate market where home prices are at a record high, (and) homeowners are smiling. (But) if you ask people who are in the industry — Realtors, mortgage lenders — they’re saying, ‘This is one of the worst housing downturns that I’ve ever seen.’ ”

Seven economists took turns sizing up this year’s enigmatic real estate market last month at the National Association of Real Estate Editors conference in Austin.

With slides, charts and statistics, they said basically the same thing: home sales are too low, and prices and interest rates are too high.

A year ago, economists said the picture was bleak because home sales had fallen to a 30-year nadir. But things would be better in 2024, they predicted.

Instead, 2024 turned out to be “the year of the head fake,” said Selma Hepp, chief economist for real estate data firm CoreLogic.

“We started off the year expecting a recovery in the housing market, and it turned out to be more of the same,” she said.

Here are highlights of what the economists had to say.

Home prices

—Home prices are projected to rise 5.7% this year, up from 3.9% in 2023, despite high interest rates and affordability challenges, according to CoreLogic’s Hepp.

— But the pace of home price growth is expected to slow during the second half of the year, said Odeta Kushi, deputy chief economist for First American Financial Corp. An increase in for-sale inventory and a pullback in demand due to high prices and limited affordability will cause price growth “to decelerate,” Kushi said.

Home sales

— Yun predicted that U.S. home sales will rise in 2024 and 2025, reaching pre-COVID levels by 2026.

He forecast that more than 5 million new and existing homes will change hands this year, up from just under 4.8 million in 2023. Nearly 6 million homes will change hands next year, he said.

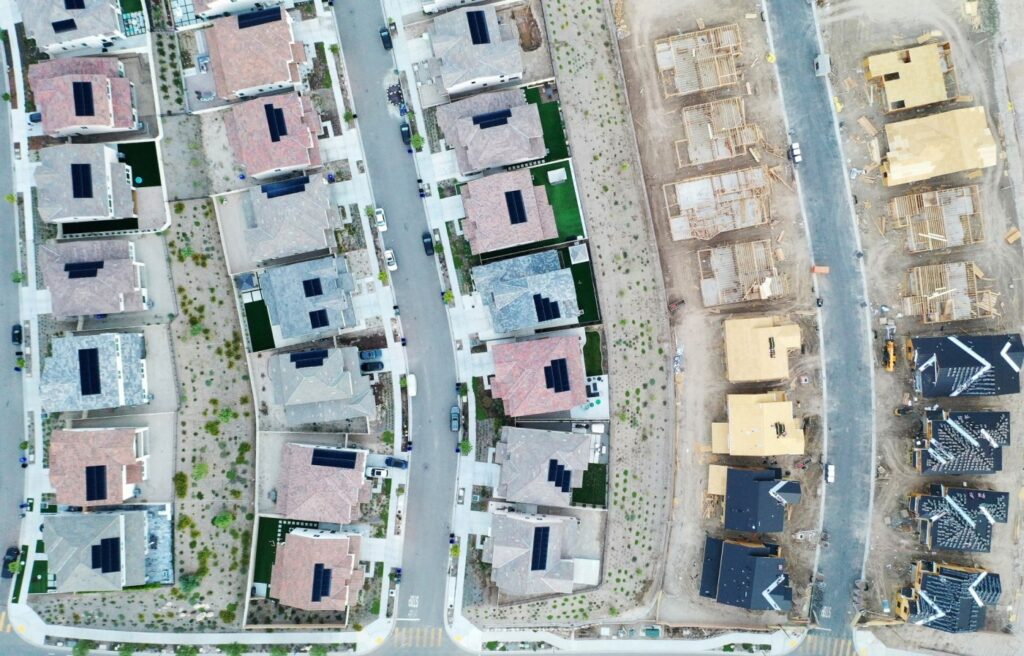

— A rise in homebuilding over the past few years boosted for-sale inventory even as existing home inventory fell. NAR figures show that new homes made up 30% of residences for sale this year, compared with 16% before the pandemic.

However, a recent drop in housing starts could reverse that trend.

Mortgage rates

— Last year, housing economists forecast mortgage interest rates would fall from an average of 6.8% for a 30-year loan to just above 5% this year. But home loan rates increased a tad to 6.9% this year so far after the Federal Reserve postponed cuts until later this year.

None of the economists provided a mortgage rate forecast for next year.

Affordability

— High home prices and persistently high mortgage rates are raising barriers for first-time home shoppers.

The typical mortgage payment for a U.S. homebuyer is up 82%, to nearly $1,700 a month, since the year before the pandemic, CoreLogic figures show. In Southern California, the typical mortgage payment doubled to $4,123 a month since the pandemic.

— Los Angeles/Orange County home shoppers lost $320,500 in buying power when mortgage rates more than doubled in 2022, said Zillow Chief Economist Skylar Olsen.

Inland Empire shoppers lost $194,700 in buying power when rates went up. San Francisco shoppers lost $394,000 in buying power.

That compares with a buying power loss of $120,100 in the nation as a whole.

“Typical homes are no longer affordable to a middle-income household in the U.S.,” Olsen said.

— A middle-income home shopper needs to put at least 81% down to afford the monthly payments in the L.A.-Orange County area, according to Zillow. In San Francisco, where incomes are higher, middle-income buyers need a 74% down payment to get an affordable payment.

“What that means is a middle-income household is not buying a home in Los Angeles,” Olsen said.

— Many younger residents are frustrated, Yun added. “They’re saying that the American dream appears to be out of their reach, or just really impossible.”

Homeowners

— Homeowners “are sitting on a ton of equity,” Kushi said, referring to the value of homes above what’s owed on the mortgage. Forty-two percent of U.S. residents own their homes free and clear.

Those people are unaffected by high mortgage rates should they choose to sell and buy a new home, she said. However, the bulk of those homeowners are boomers aging in place.

— Homeowners with a mortgage have about $17 trillion in equity, while equity for all homeowners totals about $32 trillion, Hepp said. In California, the average homeowner has $605,000 in equity.

—That rise in equity contributes to the “lock-in effect,” further limiting the number of homes for sale, Hepp said. “They don’t want to face a capital gains (tax) because of the equity gains that they’ve got,” she said.

Single owners must pay taxes on more than $250,000 in profits when they sell their home, while married couples must pay taxes on more than $500,000 in profits.

Investors

— Investors accounted for nearly 30% of single-family home purchases this year, up from around 20% before the pandemic, Hepp said.

“The number of investor purchases are down as overall sales are down, (but) their share (of purchases) remains elevated,” she said.

Apartments

— After reaching historically high levels, building permits for new apartments are slowing down, even though an estimated 4.3 million new apartments will be needed by 2035, said Caitlin Sugrue Walker, research vice president at the National Multifamily Housing Council.

Office buildings

— A downturn in the office market won’t implode the economy because banks have reserves to buffer them from real estate losses, said Richard Barkham, global chief economist for commercial real estate brokerage CBRE.

Office occupancy has been falling since the pandemic boosted remote work, causing some building owners to default on their loans. And more than $100 billion in office loans are coming due his year, according to research and data firm MSCI.

But Barkham doesn’t expect “a wave of defaults.”

If buildings are generating income, Barkham said, banks will “extend and pretend,” meaning they’ll extend the loans despite any potential financial distress.

Lenders “are not really wanting to get a whole bunch of real estate back. … They don’t want to manage real estate. They don’t want anything to do with real estate,” he said. “Defaults are increasing, but there’s no widespread fire sale in commercial real estate at all.”