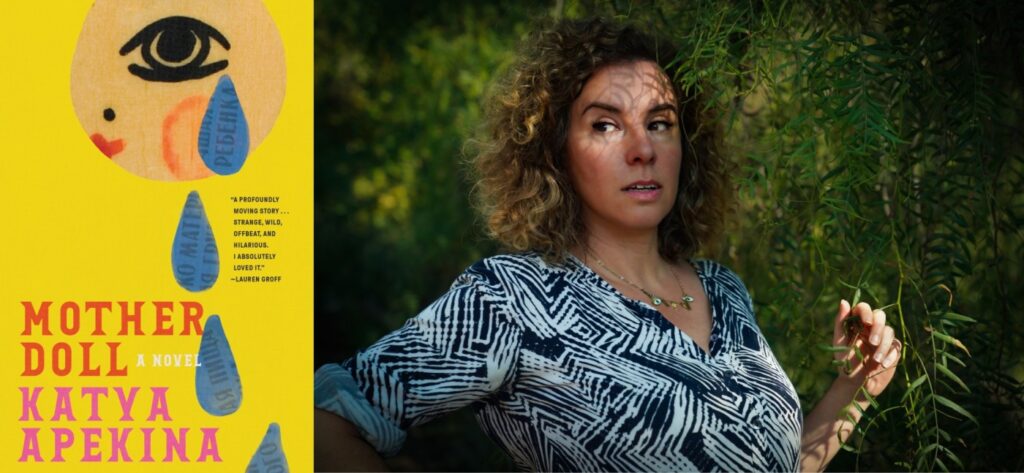

Nestled inside Katya Apekina’s novel “Mother Doll” are four generations of mothers, whose lives, stretching from the Russian Revolution through to modern Los Angeles, are haunted by the mistakes and miscommunications between the generations. Zhenia lives in L.A. while her family is back in Boston; she’s struggling to cope with her beloved grandmother’s dementia, her mother’s cold pragmatism, and her own deteriorating marriage.

Then Zhenia gets a call from a medium named Paul, who has been contacted by the ghost of her great-grandmother, Irina — she needs to tell her life story to Zhenia as a way to be able to move on from the limbo in which she is trapped. (There’s also a chorus of other ghosts à la George Saunders’ “Lincoln in the Bardo.”) Beyond the otherworldly nature of the framework, the book follows the parallel stories of Irina and Zhenia as they each try making sense of their lives.

SEE ALSO: Sign up for our free Book Pages newsletter about bestsellers, authors and more

Apekina, whose debut was “The Deeper the Water, The Uglier the Fish,” was born in Moscow but her family fled to America when she was three. She spoke recently by video from her home in Los Angeles. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q. Both of your novels are about trauma being handed down through the generations, but this time more of that derives from external forces, with the Russian Revolution and the aftermath. Were you consciously thinking about that difference?

We’re all shaped by our surroundings by whatever soup we’re boiling in without realizing that we’re part of that soup – we make the soup and we’re in the soup. But for this one, I was definitely thinking more about the impact that outside forces and groups have on an individual.

Why is generational trauma of interest to me? There must be some kernel in my own life that has me revisiting these themes. The characters and the dynamics are not similar to my family, but my family left the Soviet Union in the ’80s when they weren’t really letting people out. We were able to escape but it was very traumatic.

I start with characters and trying to understand their dynamics and then a story starts to emerge and the themes are usually subconscious, but with this book, I was doing so much historical research, reading tons of literature and journals from that period so I was probably thinking more thematically than otherwise.

And I started doing research in 2016, so it’s not unrelated to our current situation. I don’t want to draw direct parallels, but there’s a sense of destabilization that everybody is aware of in 2016 – that sense of things eroding, and you don’t know what’s going to happen. So that was on my mind when I was doing research into the Russian Revolution.

Q. Zhenia comments at one point that her brother Greg seems content and happy in a way that’s un-Russian. Are the generalizations about the Russian natural character accurate to some extent?

My brother’s Russian is better than mine, but he is sweeter, so maybe that is more American of him. For a lot of Soviet immigrants when they came to the U.S. and people were just smiling at them all the time, they found it jarring. It’s not that people in the Soviet Union never smiled but they definitely didn’t smile constantly at strangers, so it was off-putting, “Why are all these people showing their teeth at me?”

This book is immigrant culture and living between two worlds in that way, which is something I’ve experienced – we spoke Russian at home and had certain values and beliefs, and then going to school in America I’d do a kind of code-switching.

Q. You used the phrase about an immigrant being between two worlds. Is that where the framework for this ghostly visitation came from?

That’s funny – until you just said that it hadn’t occurred to me. But it totally makes sense – I am interested in these in-between spaces, emotionally, and then literally, with the afterlife.

You could see the ghost part as a metaphor but there’s Soviet magical realism that combines these magical elements with mundane everyday life that inspired me. I don’t mean that I literally believe in ghosts. I don’t know what I believe, but it’s more fun to have it be a manifestation that Zhenia can have a conversation with than if she just found her great-grandmother’s letters. That’s more like what happened to me – my grandmother gave me her memoirs, and I held off on reading them until she died. When I was reading them I felt like I was talking to her and that was the literal seed for this. But that didn’t seem as dynamic – there’s a bit of chaos that a ghost invites; I don’t know what the ghost is going to do next as I’m writing it.

Q. What drives Irina to appear?

She lived with a lot of shame as an adult, and that’s why this part of her continues to exist in the afterlife. It’s not necessarily shame about her actions in the revolution, but shame around abandoning her daughter. She’s very dishonest with herself about emotions, which isn’t the same as being factually dishonest. She has refused to even admit that she feels this shame, which is ironic because now that’s all she is – she’s just the shame that exists after death. When I was trying to write that, I wondered how do I communicate a character whose emotions are so intense and they don’t acknowledge them at all? You want to have a sense of the surface of the ocean – but you sense there are things swimming underneath without really changing the surface.

Q. How did you figure out how to flesh out, so to speak, the character of Paul?

It was so interesting to have a stranger who has nothing to do with Zhenia and Irina the way you would have a therapist who’s a neutral party. He provides an external perspective on the main characters and introduces this sense of life continuing outside of the edges of the story. It introduces air into the story, because he has his story and his life and his concerns so the reader feels the world is bigger than just Zhenia and Irina.

But I wondered why Paul, what does this mean to him? If you’re a gay man who survived the AIDS epidemic in New York in the ’80s, that’s a huge trauma and that would haunt you – so that was his motivation to get into mediumship. I just loved writing him as a character and added more of him in the revisions.

Related Articles

How an internship at LA’s Chinese American Museum launched a new Anna May Wong book

Kate DiCamillo talks about healing, love and her new middle-grade novel ‘Ferris’

For 50 years, Frank Johnson worked in secret. Finally, you can see the results.

Why Tommy Orange says the ‘epic’ survival of Native people fuels ‘Wandering Stars’

This week’s bestsellers at Southern California’s independent bookstores

Q. The book explores how we see our loved ones – parents or grandparents – and then must eventually learn to see them fresh through other’s eyes.

As a writer, you’re constantly putting yourself into other people’s experiences so you need that ability to holding many truths at once, seeing many perspectives at the same time.

In my first book, these two sisters grow up the same family, but have very different perceptions of their parents. Here Zhenia was so close with her grandmother growing up that it would feel like a betrayal to see her in any way other than how her grandmother wants to be seen. But once she dies, that opens space up in her relationship with her mother; their dynamic, which was also held in place by this triangulated relationship, can evolve. There’s a lot of triangles in this book.