The national ensign flag at local military bases will be at half-mast for 29 days, marking the death of Gen. Alfred Gray, the 29th Marine Corps commandant and legendary Marine who rose from the rank and file and helped set the foundation for how Marines fight.

“Today I mourn with all Marines, past and present, the loss of our 29th commandant, Gen. Gray,” said Gen. Eric Smith, the commandant of the Marine Corps. “He was a ‘Marine’s Marine’ — a giant who walked among us during his career and after, remaining one of the Corps’ dearest friends and advocates even into his twilight.”

Gray died on Wednesday, March 20, in his home in Virginia after a short hospice stay. He was 95.

He served as the 29th Marine commandant from July 1, 1987, to June 30, 1991, retiring after 41 years of service after enlisting as a private in 1940 and commissioning as a second lieutenant in 1952. After retirement, he remained involved with Marine initiatives programs and groups such as the Marine Corps Association and Foundation, the Semper Fi Fund, the Potomac Institute and various events.

cq comment=”The following content will display as an info box.” ]

Related links

The Marine Corps is preparing for a new fight, here’s how

Marines call the ACV the ‘future of amphibious warfighting’ despite flipping 4 times in a year

Marines revise training with new troop transport, but tell Congress it’s the right vehicle

Camp Pendleton Marines’ Cyber Games victory comes with important lesson

Marines, sailors storm beaches at Camp Pendleton at start of massive training exercise

Smith said Gray developed the doctrine that is still the foundation for the Marines’ warfighting today. Though it is only 100 pages long, Smith called it “legendary” and said it teaches Marines how to “think, prepare and execute” warfighting.

Along with setting the foundation, Gray put a focus on large-scale maneuvers in desert and cold-weather environments and robust maritime special operations.

Camp Pendleton and Twentynine Palms are examples and use their geography to facilitate large annual exercises that help Marines stay ready. Camp Pendleton covers 125,000 acres, including 17.5 miles of shoreline, perfect for amphibious assault training. Inland at Twentynine Palms, Marines train constantly, and there is enough maneuvering space to facilitate brigade-size (15,000 Marines) training exercises.

As a bonus, the Navy’s San Clemente Island — 55 miles west of Orange County — is one of the military’s most valuable assets as the nation’s only ship-to-shore live-fire training range. The region is home to 85% of the Defense Department airspace for training maneuvers and 67% of the Marine Corps’ live-fire training ranges.

While embracing the fundamentals of warfighting, Gray believed in educating Marines and valued critical thinking. In 1989, he established the Marine Corps University. He required them to read books on various subjects relevant to their duties, which became known as the “Commandant’s Reading List.”

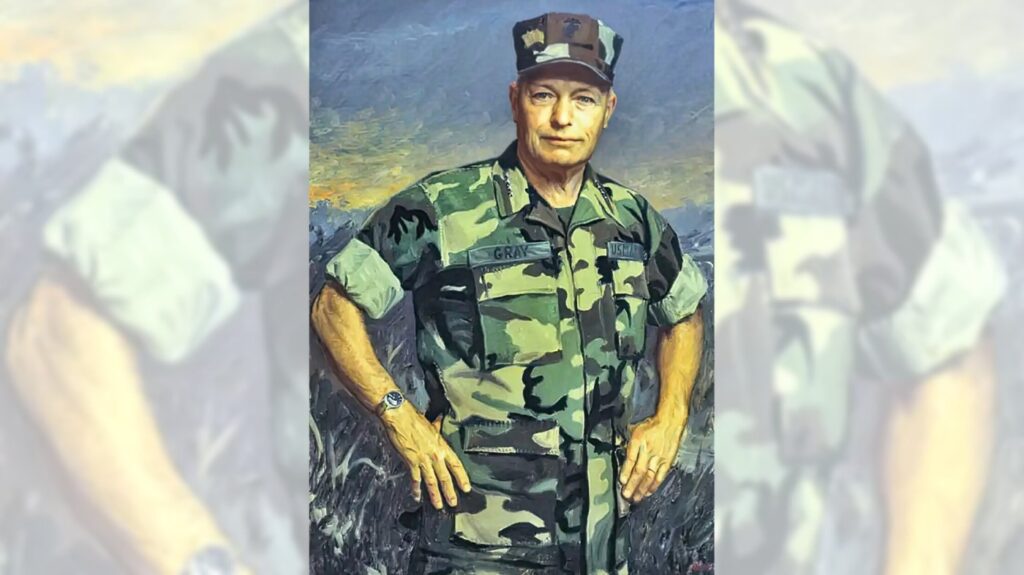

He became well-known for being the first commandant to have his official photograph and portrait taken in the camouflage utility uniform. He said, “Every Marine is, first and foremost, a rifleman. All other conditions are secondary.”

Charlie Quilter, a Marine fighter pilot and military historian, sees that focus on the troops as one of Gray’s most significant impacts.

“I think his service as an enlisted man in Korea gave him a bottom-up view of what it takes to be a leader,” said Quilter, adding that Gray made important changes in the Corps’ culture.

“He pushed the concept of ‘maneuver warfare,’ a fast-paced form of warfighting in which leaders in the field understood the intent of the commander and were empowered to exploit situations that otherwise might be lost while bucking a decision up the chain of command,” Quiter said. “And by leaders, he meant even corporals and sergeants on the pointy end right down to the squad level. This was a real cultural revolution.”

Quilter remembered meeting Gray in Saudi Arabia as Desert Storm was building up and described him as “an older but stout Marine” walking alone outside a secure area.

“This was against orders, so I caught up with him,” Quilter said. “Colonels don’t say ‘sir’ to many, but as he turned around, I saw the four stars, which could only mean this man was the commandant of the Marine Corps. Thinking quickly, I said, ‘Sir, can I help you? This is not a secure area, and I’d feel really bad if somebody knocked off the Commandant while I was nearby.’”

“He laughed, and I do think he actually was a bit lost in the dark,” Quilter said. “I escorted him back to his hut in an abandoned but secure oil workers camp.”