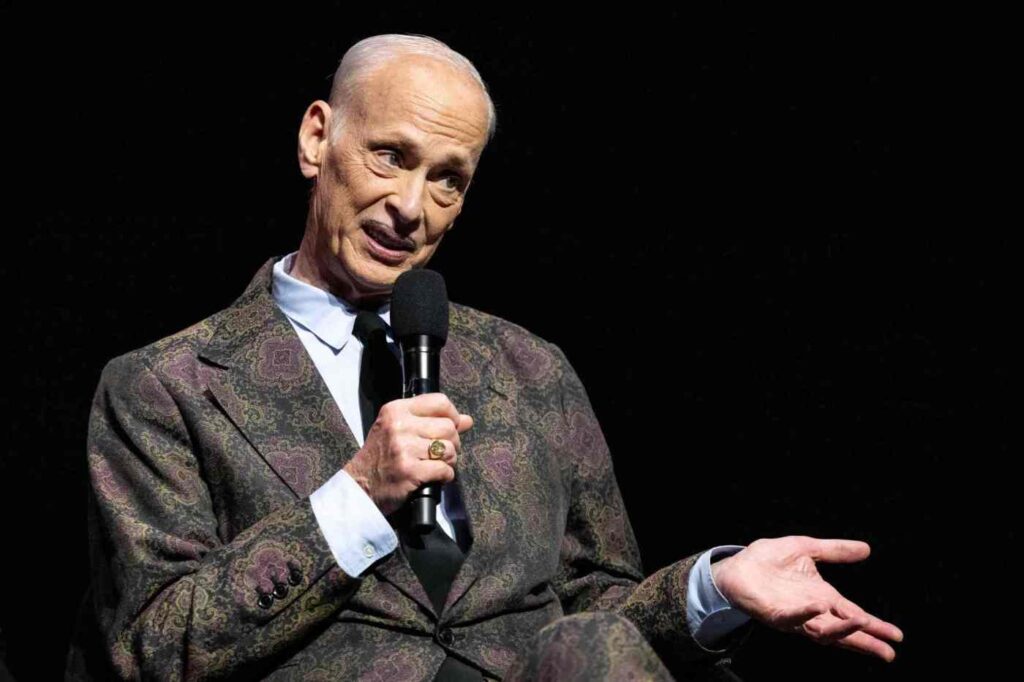

John Waters, the writer-director of films from “Pink Flamingos” to “Hairspray,” was in his element.

An entire floor of the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures was about to open with the first-ever museum exhibit, “John Waters: Pope of Trash,” on the beloved cult filmmaker’s career.

A sizeable media throng had assembled to capture Waters’ words and cruise through 12 galleries that tell the story of his rise from a teenage guerrilla filmmaker to something close to mainstream acceptability.

“I’m so respectable, I could puke,” he noted at one point, smiling beneath his trademark pencil mustache, a twinkle of glee in his eyes.

Museum director Jacqueline Stewart asked him how it felt to see his life laid out in these galleries during a press panel on Thursday, Sept. 14.

“Welcome to the trash can of my memories, right?” Waters replied, laughing. “It’s amazing. I didn’t really know what to expect. I just saw it yesterday for the first time, and it was just an amazing thing.

“From Lutherville to here,” he said, marveling at the journey of this kid from a small town on the outskirts of Baltimore.

At 77, Waters has outlived many of the family and friends who helped him make his way from would-be teen auteur to Hollywood. But he’s never forgotten them – those who are living are still close friends today; those who are gone he remembered in his conversation about his life and career.

“My parents, I honor them with this,” Waters said. “I wish they could be here because they always made me believe that I could do whatever I want to do, even though they were horrified by what I was doing.

“I thought they just figured, ‘What else could he do? It’s this or jail,’” he said the laughter of the preview audience. “Because if I hadn’t had the outlet to use all my antisocial lunatics that I put in my scenes, who knows what would have happened?

“But it feels great to be here, with no irony at all. I’m just happy I’m alive for it.”

Films and friends

Waters, whose ’70s films “Pink Flamingos,” “Female Trouble,” and “Desperate Living,” gave him a reputation for over-the-top – or beyond-the-pale – storytelling, has always delighted in shocking audiences. But his boundary-pushing work always came from a place of love for his oddball outsider characters.

Visitors to the exhibit enter through a church-like theater – his earliest films, such as “Hag in a Black Leather Jacket,” “Roman Candles,” and “Eat Your Makeup,” got their first screenings in Baltimore church halls that Waters rented. A montage of his work screens at the front of the room. The walls are lined with faux stained-glass windows that depict some of his regular stars: the drag queen Divine, his close friend and muse, Edith Massey, and Jean Hill among them.

From there, guests flow into a gallery dedicated to his lifelong collaborators, including actors such as Mary Vivian Pearce, the only actor to appear in all of Waters’ films, along with Mink Stole and David Lochary. Then there is his behind-the-camera crew, such as art director Vincent Peranio, whose archives at Yale University provided material for the exhibit, and casting director Pat Moran.

“I don’t trust people that don’t have old friends; something’s the matter with them, ” Waters said of his practice of using the same actors, many of whom were amateurs when he started his career, throughout his films. “You know, Facebook isn’t friendship. You have to get your hair done, you have to meet people, you have to remember their birthday. Not ‘likes.’

“So they’re also my friends in real life,” he said. “When we’re not making a movie, I see them just as much. When we moved on, I still used all the original people in my movies with Hollywood movie stars. And for the most part, I’m still friends with all the Hollywood movie stars, too.”

That same gallery also includes artifacts from Waters’ childhood and earliest filmmaking efforts in the ’60s. A hand-written flyer announcing the return of his neighborhood puppet shows demonstrated his interest in art and business as a child. The small notebooks filled with expenses and revenues for his first few films are among Waters’ favorite pieces in the show.

“The little things in the cases, like my original notebook that had receipts of 26 cents for scotch tape and everything for the movie,” Waters said. “And then the grosses. You’d look through I’d have $32 and $10. And it would add up and I would pay my dad back. I did always pay him back, you know.

“Then I learned how to raise money to make the other movies and they all got paid back, too,” he says. “Not all the studios did. I think by now most of them have. It just took a while.”

From the core to the casual

Co-curators Jenny He and Dara Jaffe started working four years ago on “Pope of Trash,” a sobriquet bestowed on Waters by Beat Generation elder statesman William Burroughs.

Their goal for the exhibit focused on three different audiences, he said.

“First are John’s devoted fans,” she said. “These are the folks who line up for your book signings; they see every one of your one-man shows, and they come out to Camp John Waters every summer in Connecticut. We wanted to make sure that our exhibition spoke to this core audience.”

The second group included more casual fans, she said, those who know “Pink Flamingos” and “Hairspray” and the Johnny Depp-starring ’50s rocker film “Cry-Baby,” as well as Waters on appearances on everything from “The Simpsons” and “Homicide: Life on the Street” to “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel” and “Bubble Guppies.”

Last, he said, were those who might not know Waters at all, but could come to the exhibit and walk away as new admirers.

“Or flee!” Waters quipped.

In the exhibit, the films are presented in chronological order in successive galleries. The three ’70s “trash” classics share a room, with the original trailer for “Pink Flamingos” – not a single clip from the film, only fan reactions and review quotes – on a loop inside a replica of the pink-and-green trailer in which Divine lived in that film.

“Polyester” marks his first Hollywood movie, and after that come some of his best-known works: “Hairspray,” which later became a Tony Award-winning musical, “Cry-Baby,” which starred Johnny Depp, and “Serial Mom,” in which Waters sent-up true-crime with Kathleen Turner in the killer title role.

All of the movie galleries include collections of costumes – “Hairspray” might have the most, though “Serial Mom” presents itself cleverly as a staged crime scene with the outfits behind yellow police tape – as well as posters, handwritten scripts on yellow legal pads, and newspapers, which include both real clippings that inspired parts of films and the fakes that Waters loved to pepper throughout his movies.

“To me, this links back to the repeated theme of infamy,” Jaffe said during the panel discussion. “Because if you’re in the news, you’re newsworthy, and for so many of John’s characters that is the end goal, no matter what it takes.”

Waters agreed, noting that infamy or fame, was often embraced, exaggerated, or made fun of by the outsiders who populated his films.

“My mother once told me when I was young, and I defied these rules, which I said at her funeral when I spoke,” Waters said. “She said, ‘Fools’ names and fools’ faces always appear in public places.’”

Now, through August 2024, Waters’s face is everywhere at the Academy Museum.

His mother would love it.

Related Articles

Comedian Tracy Morgan shares what keeps him laughing before headlining Morongo Casino

What exodus? 37 reasons to stay in California

How family meals offer mental and physical health benefits

I was a Calico Ghost Town monster at Knott’s Scary Farm and left people screaming in fear

How the San Fernando Valley in the ’90s inspired ‘Rana Joon’ author