POMONA — Neto Mercado was dazed, stumbling down a path toward certain defeat. A young man punching wildly, living dangerously. Break-ins. Shootouts. Fights. In his corner: Gangsters and luck. To hear him tell it now, he was as addicted to adrenaline as anything, having too much fun to stop and think about the damage he was doing.

In his other corner, at home: Tito. And Tito wasn’t giving up, not without a fight, turning to boxing to try to lure Neto in from the wild.

Tito, by the way, is the kid in this scenario.

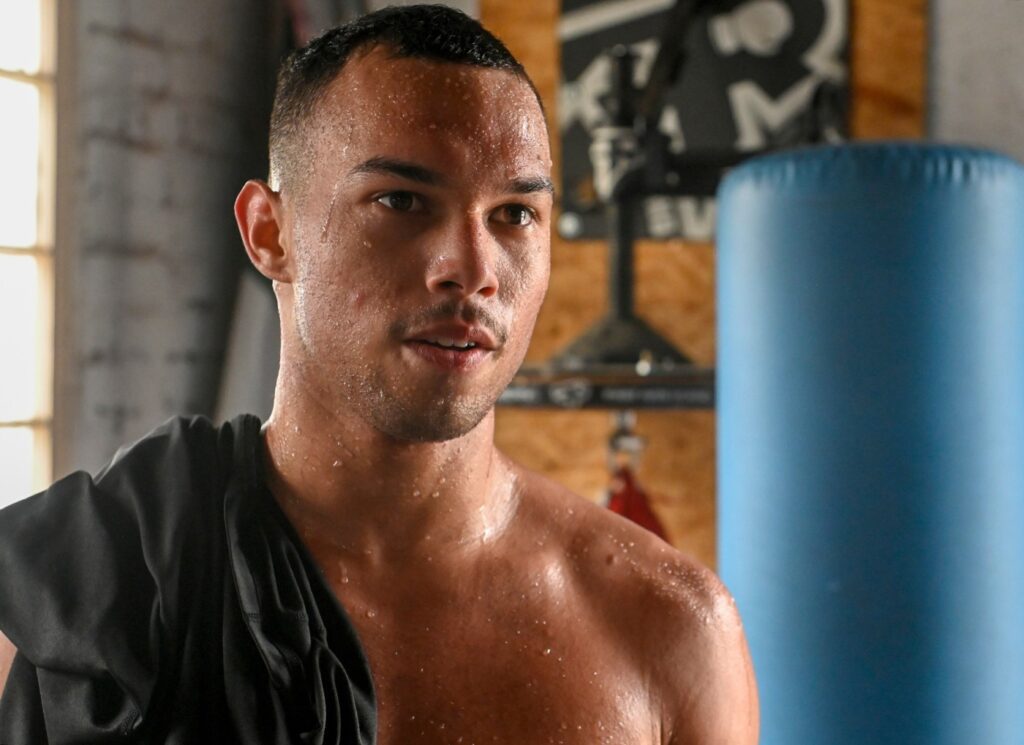

The little boy who’s grown into an ascendant 21-year-old super lightweight. You’ll want to remember his name: Ernesto “Tito” Mercado. And while you’re at it, file away his younger brothers’ too: 18-year-old Daniel and 10-year-old Damian.

Ernesto “Neto” Mercado is the trainer. Their dad.

He’ll deflect credit, testify that their story is predestined, God’s script. That time his younger brother asked him – he’d boxed a little – for some training? How that scene inspired 4- or 5-year-old Tito, put it in his head that if he wanted more time with his dad, really wanted to get his attention, he should box too? And not just box, but get good at it? God did that.

And thank God for Tito’s adaptability and determination – more important than raw talent – that turned him into a prospect in need of a coach. And for letting Neto see that he was that coach.

“I’m not leading the ship, God is,” Neto says. “And at the end of the day, when they’re boxing, I know that God is the referee inside the ring.”

In that case: Good lookin’ out up there.

Boxing as a godsend? We’ve known.

That such a punishing sport could save a person from a life of pain? Not much of a reach.

What’s refreshing is how, in the Mercados’ case, it’s engendered such a warm and welcome reliance. United a family in pursuit of a shared dream – a journey that continues Saturday, July 8, in Managua, Nicaragua, where Tito will fight South African veteran Xolisani Ndongeni (31-2, 18 KOs) in a bout scheduled for 10 rounds.

What’s so cool is that the sport has brought so much love into the storefront space on Holt Avenue. Infused so much trust into the gym wallpapered with faded newspaper clippings, posters of fights past and a big Claremont Toyota “Oh baby!” banner – an homage to the sponsor that helped build the boxing sanctuary that reliably serves Neto’s kids and so many others in their neighborhood through their Gangs 2 Grace Youth Foundation.

Back in the ’90s, Sports Illustrated’s Gary Smith wrote a profile on Roy Jones Jr. and his complicated relationship with his dad: “There are virtually no good stories to tell in the history of boxing fathers and sons.”

Neto is no Roy Jones Sr., no stage mom, no Little League dad. He can expertly push and prod, sure, end a call and not pick back up. Leave Tito hanging, halfway across the world, because he needed to learn that he can figure it out himself. But Neto doesn’t raise his voice to deliver tutelage during sparring and won’t curse out his boys after a bout, even if they’ve lost. All he can bring himself to say then is that he’s proud, and, likely, that the judges got it wrong.

A little tough or a lot tender, it’s all love.

Pound-for-pound some of the most potent stuff on the planet, manifested in the Mercados’ gym as rounds and rounds of family time.

NO LIES TOLD

I’m not gonna lie to you. That phrase, which peppers the Mercados’ speech, has long been a favorite of mine, if only because whatever a person says next is probably gonna be good.

“I’m not gonna lie,” Tito says, “at tournaments, I would go play basketball. Michael Jordan, sometimes he would go play golf for two, three hours (before games), so I would do things like that too. Sometimes I would jump up weight classes for the heck of it. Different things as a way of challenging myself, ’cause sometimes I would get bored. I don’t want to say it was too easy, but I wanted to challenge myself.”

“I’m not gonna lie, bro,” Neto tells Darryl Hayes, a fighter he’s flown in from Houston to spar with Tito and Daniel. “My stomach’s been hurting. I’m thinking, like, ‘Do I have something?’ And then I realized that the last two weeks, I was getting hit in the body protector. You see how thick it is, the pad? It doesn’t matter. It’s painful. I lost friends because they’re like, ‘Nah bro, you’re setting me up every time I go over there, you want me to put that on. I’m not coming anymore!’”

“I’m not gonna lie to you,” Neto says also, recalling the first time he approached the pastor at Southern California Dream Center, the Pomona church, to see if he could train boxers there. “I was tweaked out. And the pastor, he goes, ‘Your pupils are so big! You came high to my church?! Man, you are different, bro. Got some guts to talk about you want to work with kids and you’re on some (stuff).”

“But then,” Neto recalls, “he was like, ‘Come back in two weeks. Clean your (stuff) up.”

So Neto did.

Go back.

“I still came back the same way,” he said. “He just didn’t notice.”

He remembers training Tito from 4-7 p.m. and being out looking for trouble by 8 or 9. Brawling with sparring partners. He’s well aware of the reputation he earned with referees and the USA Boxing people.

Eventually, though, as weeks in the gym became months became a year and then years, Neto found himself leading with his right foot.

“Boxing kind of helps you get those bad habits away because it gives you a more cleaner lifestyle,” Neto said. “The fighter’s getting discipline and the coach is getting discipline, too. If he can’t drink, I can’t drink. Because how am I gonna go in the corner with him and be not of sober mind?”

A KNOCKOUT ARTIST

Tito boxed competitively as soon as he could, at 8. Cried after the first fight, because he’d worked so hard and lost – something that didn’t happen against that opponent again: “I beat him again within that same year and I beat him again when we were 11, and I beat him again when we were 12. … He’s more of a social media boxer now.”

Neto’s boy, meanwhile, has lost only 10 more times. That’s over the course of another 277 amateur fights. And never in 10 pro bouts so far, every one of which has ended the same way: By knockout, all but two of them finished before the third round.

So Tito has a reputation now, too. He has people talking about him as a fighter who can outbox you or hurt you, a heavy-handed tactician who is as patient as he is powerful. One fight fan from New Jersey, a bettor, tells me if he could buy stock in fighters, he’d buy it in Tito.

“He brings a lot of entertainment,” confirms Damian, the fifth-grade brother who spends more time at the gym than anyone besides Neto, seeing everything, soaking it all in.

If Damian isn’t training, looking like a mini Tito, he’s there handing out Gatorade and water. Or recording sparring sessions from his perch atop an exercise ball. Or smothering Tito’s face and helmet with vaseline, that age-old practice used to protect fighters from bruises and cuts – a picture of love if ever there were.

“I already know,” Damian says, “Tito always beats everybody.”

That could be bad news for Ndongeni, Tito’s next opponent.

“In July, he’s gonna be 11-0,” Daniel says. “I predict that the guy doesn’t survive past the third round.”

Tito can spin a bedtime story, for sure, but he thinks the best part is what happens before the K.O.

“I feel like I get more joy out of seeing the fear in a man’s eyes than if I knocked him out. That gives me more of a dominant feeling,” Tito says. “Because once you knock him out, for that split-second, it’s exciting. You hear the fans rumbling. But then once that guy’s out, it’s like, damn, he’s just sleeping.”

That’s someone too scary to add to a top name’s dance card, at least not until Tito’s brand is big enough to make facing him worth the risk.

So the Mercados are being intentional, committed to making forward progress: After Tito faces Ndongeni, he has two more bouts slated, for Aug. 26 and Nov. 11, in Ontario, against opponents to be determined – those fights and the one this week in Nicaragua all to be presented by Fight City Promotions, Neto’s company.

And even if Mercados can’t yet get the fighters they want – Gervonta Davis, Shakur Stevenson, Keyshawn Davis – they’re making their statement by beating up on common opponents. Take Jose Zaragoza, whom 10th-ranked Davis beat via second-round TKO in 2021, a few months before Tito knocked him out 1:07 into Round 2.

“The built fighter, they’ll fight a bunch of tomato cans,” says Hayes, whose unenviable job it was to mimic Ndongeni’s movement around the ring. “People who just gonna sit there and let you beat them, you know? They’re not doing that at all.”

Tito’s known as someone who goes about things the right way, said Ali Hangan, who had him in government and economics classes and as a meticulous teacher’s aide at Pomona High School, from which Daniel – and “Sugar” Shane Mosley – also graduated.

“I’ve been teaching for 26 years and a lot of great kids have come through, but there are some that are just on a different level,” Hangan said. And Tito? “He’s a born leader, for real.”

He wanted badly to represent the United States at the Olympics, but he was jilted by USA Boxing. And then an opportunity to fight for Neto’s native Nicaragua was interrupted in 2020 by COVID, and Tito’s Olympic dream was deferred permanently.

A pro since 2021, Tito has another goal now: world champion.

But he’s in no rush. Pro boxing allows more than just three rounds to work, so he doesn’t have to overwhelm an opponent immediately. He can pick his spots.

The only thing that scares him, he says, is the feeling that might be waiting for him once he’s fought his way to the top of the world: “I’m more or less scared of catching it too quick. Like the journey, right now, I’m having fun.”

Taking his time, savoring his victory. Enjoying his dad.

‘DIFFERENT TYPE OF ADRENALINE’

The last time I visited the Mercados’ gym and was talking with Neto, someone turned down the music – ’90s rap mostly – a bit.

Whoever lowered the volume, Tito or Daniel, I figured he’d done it to be courteous; they’re pull-out-a-chair-for-a-lady kind of guys. But maybe they also wanted to hear what Neto had to say, because they parked themselves at our feet, an attentive audience silently doing ab work and chiming in only when he asked for affirmation.

“Hey, Tito, the fight in Bulgaria was a really hard fight, huh?”

“Tito, remember when you used to work my corner when I used to spar?”

And, rhetorically: “Tito, how tall am I?”

His sons are listening, I’m pretty sure, when he says: “People ask, ‘What are you doing in the boxing gym? You train your kids too much.’ But, like, would you rather them be doing drugs?

“Because I was with the business, you know? It was adrenaline. But this is a different type of adrenaline. The different type of adrenaline I get here is through my kids. And it’s more satisfying to me, to see them succeed.

“It’s safe here. I feel good here. Life is great. I couldn’t be in a better position than them right now in life. We’re not rich, we’re not doing great like that, but just having my family, my kids, it’s good enough.”

Related Articles

Swanson: Trade for James Harden? Clippers have to try

Swanson: NBA free agency is all the rage, but have you watched kids play basketball lately?

Swanson: Rickie Fowler offers up a fine Father’s Day gift – a reason to sweat

Swanson: Murrieta homeboy Rickie Fowler leading the U.S. Open? What we always expected

Swanson: Grouped with LIV star Brooks Koepka, Rory McIlroy has upper hand