The business school where I went for my master’s in the early 1980s practically invented the concept of globalism in our commerce with other nations.

When Lt. Gen. Barton Kyle Yount came home from World War II, he was fixated on the fact that his countrymen, isolated here in our big country on a big continent, were more or less yahoos when it came to understanding the rest of the world. We were monolingual; didn’t know much of the histories or cultures of other places; didn’t know how to do business with anyone else.

So he bought the old Thunderbird Field air base in Glendale, Ariz., outside of Phoenix, and founded the American Institute for Foreign Trade, offering degrees in the field.

Along with learning how money flowed internationally, he insisted that every student take a foreign language in order to receive a degree, and linguists there created a simple new way of studying — tiny classes every single weekday morning, eight students and a professor, all conversational. We had to memorize a taped dialogue every night, and then play either Person A or Person B in class.

In my day, the name had changed to the American Graduate School of International Management — but everyone just called it Thunderbird. Now, swallowed up by Arizona State University, it’s the Thunderbird School of Global Management, a division of ASU, with a separate downtown Phoenix campus.

We were present at the creation of the idea that countries ought to do what countries do best, business-wise. Raw materials? Mine them and sell them to everyone else. A huge labor pool eager for work? Build stuff, more cheaply than anyone else can. Good at logistics? Create massive new shipping lanes and move the stuff around. If the United States, for instance, would stand to lose a lot of manufacturing jobs, other kinds of jobs would be created; we would invent stuff, and have it built elsewhere, and that stuff consumers were clamoring for would be cheap, and even increasingly well-made. All boats would be lifted.

So it worked, right? Until it didn’t.

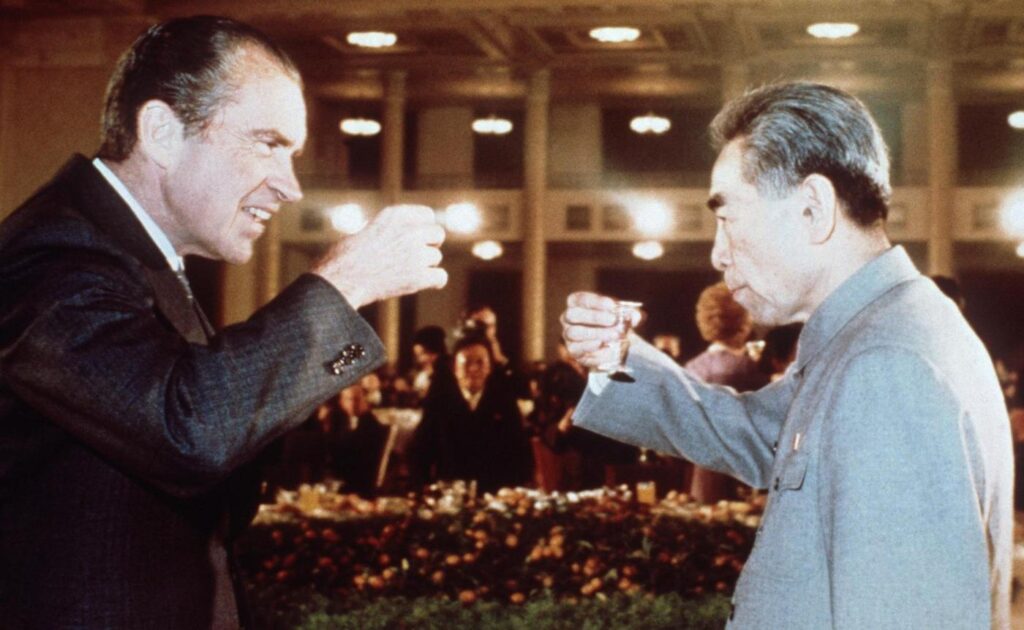

Globalism, it turned out, didn’t account for the havoc that could be wrought by a worldwide pandemic during which factories closed down for fear of mass infections of a deadly disease. It didn’t account for the supply chains that would be so deeply affected. The hopes — the seeming sureness — that the huge economic boom the West essentially created in our leading trading partner, China, would also create democracy and a shared commitment to intellectual freedoms and human rights went south. It didn’t account for the climate emergency which, while already gaining steam, would be greatly stoked by all the fossil fuels burned up in moving the stuff and the people around the globe. Nor that former superpowers like Russia, left behind by all the new freedom, would lash out in fury at its loss of empire.

“Failures of Globalization Shatter Long-Held Beliefs” was the headline above Patricia Cohen’s lead story in last Sunday’s New York Times. “War and Pandemic Highlight Shortcomings of the Free-Market.”

Five years ago at Davos, Christine Lagarde, then managing director of the International Monetary Fund, could smile as she said the global economy “is in a very sweet spot.”

In 2023, Cohen writes, “it has suddenly seemed as if almost everything we thought we knew about the world economy was wrong.”

Next week I’ll interview Sanjeev Khagram, Thunderbird’s director general, about globalism 2.0. He’s an optimistic guy. Maybe he can point to a good way forward from this mess.

Larry Wilson is on the Southern California News Group editorial board. [email protected]