By ADAM BEAM

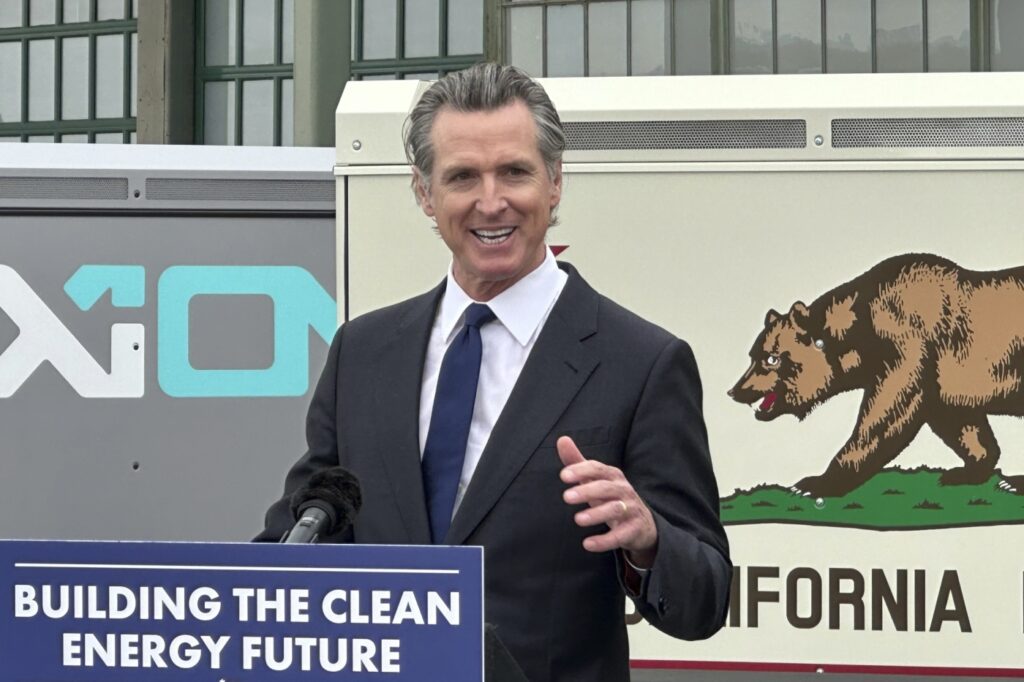

SACRAMENTO — California Gov. Gavin Newsom and the Democrats who control the state Legislature agreed late Monday on how to spend $310.8 billion over the next year, endorsing a plan that covers a nearly $32 billion budget deficit without raiding the state’s savings account.

The nation’s most populous state has had combined budget surpluses of well over $100 billion in the past few years, using that money to greatly expand government.

But this year, revenues slowed as inflation soared and the stock market struggled. California gets most of its revenue from taxes paid by the wealthy, making it more vulnerable to changes in the economy than other states. Last month, the Newsom administration estimated the state’s spending would exceed revenues by over $30 billion.

See more on the California budget: Climate, business groups clash over Newsom’s proposed environmental law reforms

The budget, which lawmakers are scheduled to vote on this week, covers that deficit by cutting some spending — about $8 billion — while delaying other spending and shifting some expenses to other funds. The plan would borrow $6.1 billion and would set aside $37.8 billion in reserves, the most ever.

“In the face of continued global economic uncertainty, this budget increases our fiscal discipline by growing our budget reserves to a record $38 billion, while preserving historic investments in public education, health care, climate, and public safety,” Newsom said.

Republicans criticized the budget plan as unsustainable, noting it would leave the state with projected multi-billion dollar deficits over the next few years. They said the state’s gas tax is scheduled to increase on Saturday, an automatic adjustment that is tied to inflation. Republicans have repeatedly tried to halt those increases, but to no avail.

“What do Capitol Democrats have in store for you this holiday weekend? Higher gas prices!” Assembly Republican Leader James Gallagher posted on Twitter.

Budget talks stalled over the weekend as Newsom sought major changes to the state’s building and permitting process. Newsom said the changes are needed to speed up vital construction projects, including expanding the state’s energy capacity and upgrading the state’s aging water infrastructure.

But a group of lawmakers from the Central Valley feared Newsom was using the proposal to push through a long-delayed project to build a giant tunnel to send water to Southern California. In the end, Newsom got most of the changes he wanted — but lawmakers made sure the changes wouldn’t benefit the tunnel project.

The budget includes a lifeline for public transit agencies struggling to survive following steep declines in riders during the coronavirus pandemic. It allows transit agencies to use some of the $5.1 billion in funding over the next three years for operations.

Still, some San Francisco Bay-area lawmakers said the spending wasn’t enough to forestall painful service cuts over the next few years. Monday, they proposed legislation that would increase tolls on seven state-owned bridges — including the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge — by $1.50 over the next five years. State Sen. Scott Wiener, a Democrat from San Francisco who supports the proposal, said it would generate $180 million in revenue.

Democratic state Sen. Steve Glazer said he would oppose any toll increase, saying in a statement “Transit riders and taxpayers have witnessed first hand the trail of broken promises by advocates for bridge toll increases.”

“The status quo is failure and we should not put in another penny to support it,” he said.

The budget does not raise income taxes to cover the deficit, but it does impose a new tax on managed care organizations — private companies that contract with the state to administer Medicaid benefits. The tax would generate an estimated $32 billion over the next four years.

Some of that money would go toward increasing how much money doctors get for treating Medicaid patients. It would also offer $150 million in loans to hospitals that are at risk of failing. That’s in addition to $150 million lawmakers approved earlier this year.

“In good years, we buckled down so that in tough years this one, we could meet our needs,” Senate President Pro Tempore Toni Atkins said. “That pragmatic approach works for household budgeting, and it works for state budgeting.”

Related Articles

Climate, business groups clash over Newsom’s proposed environmental law reforms