In 1998, journalist Dean King went on a family trip to Yosemite National Park for the first time.

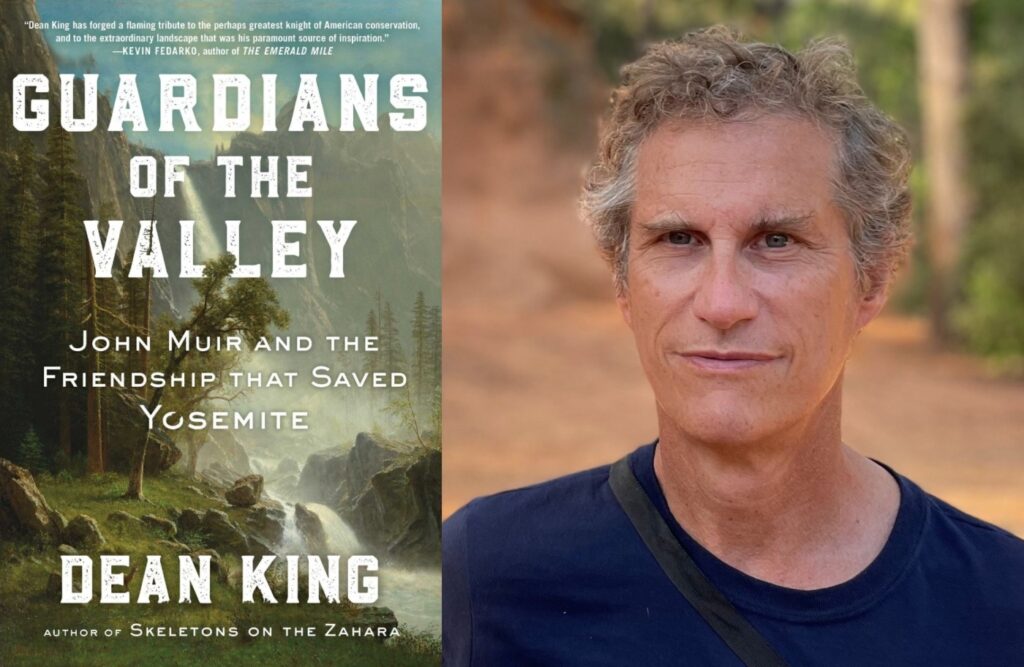

“Inspiration Point, true to its name, was incredibly inspiring,” King recalled recently in a video interview about his new book, “Guardians of the Valley: John Muir and the Friendship that Saved Yosemite.” “The magnificence and the scale really redefined how I thought about America. I knew at that moment I wanted to write about Yosemite.”

Related: Sign up for our free newsletter about books, authors, reading and more

It took years as King worked on other projects. His research led him to John Muir, who is heralded as the man who helped save Yosemite. As he dug deeper, however, he realized that Muir’s work was really done in tandem with Robert Underwood Johnson, who was in many ways Muir’s opposite – an urbane New York publisher who worked with everyone from President Ulysses S. Grant to Nikola Tesla.

The two men became fast friends – it was Johnson who encouraged Muir to form the organization that became the Sierra Club – and it was their work together that both cemented Muir’s legacy and helped preserve Yosemite and lay the foundation for nearly 150 years of environmental activism.

There has been controversy and concern about Muir’s racist views, which King writes about in the book, and the Sierra Club has addressed Muir’s complicated legacy. In a statement accompanying the release of the book, King said, “In his younger years, Muir was occasionally critical of Native Americans and Black people in specific incidences … it was interesting to me to see that as Muir matured, he frequently wrote about our shared humanity and rejected prejudice.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity

Q. Robert Underwood Johnson and John Muir seemed to complement each other perfectly.

Without Johnson, Muir would be a literary footnote, next in line after Emerson and Thoreau. He would not have had the huge impact he had because he was frustrated by the political world. He was more social than people might think, but he did not want to be thrust into the spotlight. Johnson was the one telling Muir he has to do more writing and to go beyond that.

He persuaded Muir to found what becomes the Sierra Club and they chose him as president. Muir’s letter-writing campaigns mark the beginning of our grassroots environmental movement. At one point, he said, “Johnson, you’ve turned me into a lobbyist!” but he was proud of that work.

Q. Muir had a full life, hiking up to Alaska and a thousand miles to the Gulf of Mexico, meeting with the likes of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Teddy Roosevelt. How did you narrow all that down?

I read ‘A Thousand Mile Walk to the Gulf” and thought it was amazing, and I wanted to write all about this but it ended up being a paragraph.

Muir was a great man but the reason he’s not better known is that he’s a polymath who did so many things and went in so many directions that it’s hard to get your arms around his story. His trips to Alaska were also fascinating but my job was to cut to the chase of why Muir is important. I preserved some of the early stuff because it helped form him.

Q. He seems to be a pragmatic visionary.

That’s a very fair assessment. As an inventor, he made machines, like a rotating desk out of clockworks and whittled wood. When he ran out of money, he worked for a broom and shovel handle factory and made changes that grew the business by 150 percent and he went to Indianapolis and made improvements for the wagon wheel. But all that time he was trying to figure out what he wanted to do. He wanted to do something for humanity to make the world better.

Q. President Lincoln gave some of what’s now Yosemite National Park to California to preserve. Why was that not enough for Muir?

Lincoln only saved Yosemite Valley. Muir had worked as a shepherd there and saw the sheep were devouring everything in the hills – they don’t just eat the greenery, they eat the roots. He realized if you destroy the grounds around Yosemite, you’ll destroy Yosemite too – there’ll be erosion, the creeks will fill in and it will eventually ruin the valley. He said just saving the valley was like saving the palm of the hand without the fingers. You have to save the whole thing to preserve the functionality.

Muir wasn’t some purist trying to prevent people from going to the mountains. He wanted to protect nature but he saw God in the mountains and wanted to bring people there.

He took Johnson when he came out there in 1889 and Johnson immediately saw the beauty, but also how it was getting ruined by not being cared for properly. Johnson says, “You write me two articles and I’ll go to D.C. and put them on the desks of all the congressmen and we’ll get a bill passed.”

They created the doughnut around the hole that was the state park. The state did not want to give their park back to the federal government so that took a long time.

Q. They lost the battle to preserve Hetch Hetchy, which was dammed up to provide water for the Bay Area. You say that it was when environmental activists learned how to fight the government but you could also see it as the first of endless losses to government or corporate interests.

There’s always going to be that tension between the need for growth and the benevolence of thinking about future generations. This battle is the first big national environmental battle and part of its legend was that it broke Muir’s heart, but when you look at his letters, he says in essence, “We did what we could do and right will prevail.”

Related Articles

How John Sayles transformed ‘Jamie MacGillivray’ into an epic historical novel

This week’s bestsellers at Southern California’s independent bookstores

The Book Pages: Bookstores! Bookstores! Bookstores!

15 must-read books coming from S.A. Cosby, Luis Alberto Urrea, Ivy Pochoda

The ‘Secret’ of rock stardom fuels Jessamyn Violet’s new novel and concert tour

His faith never wavered. We have to keep searching for ways to muddle through the problems we create for ourselves. There’s still a movement to take the dam down as people come to realize the benefits of undoing what we’ve done. At some point, it is a possibility. There are now too many people coming to Yosemite but there’s another Yosemite out here under the water. It would be nice to have that wild part of the park back.

Q. Do you hope the book inspires people to take up that cause of environmental activism?

I’m hoping this book and Muir’s story offers a positive approach to what we’re facing – the way we’ll solve our problems is by having people fall in love with nature. When you get into the weeds of what people need to sustain practical, profitable lives, there’s a lot of conflict. You really can’t browbeat people into doing stuff they don’t believe in. But the more people who love nature, the more people on both sides will want to try to make changes because they realize the value of nature.