It’s been a landmark year for Mahtab Mohammadi.

The Iranian American artist, an MFA student in drawing and painting who also teaches beginning painting and drawing classes at CSUF, celebrates her 10th anniversary of immigrating to the United States.

She left her home country in her early 40s, a transition she said was financially, culturally, and emotionally challenging.

But she’s flourished here as an artist.

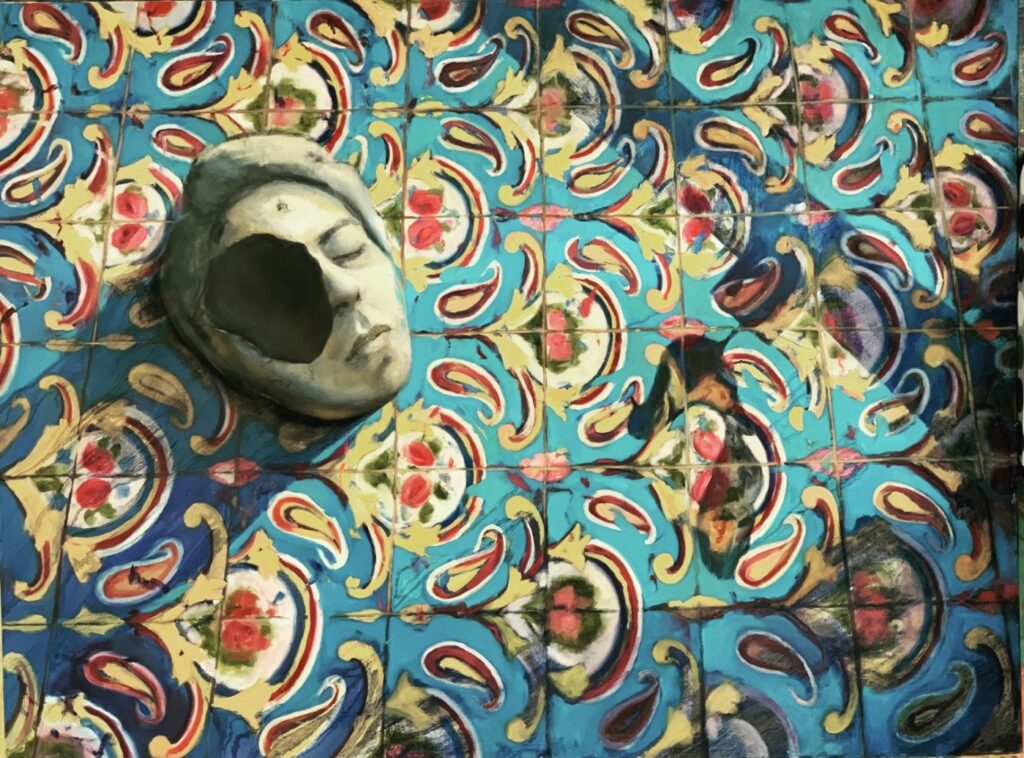

In her colorful works, Persian, Western, and pop culture images reflect her bitter memories of the discrimination, war, and violence against women and gender minorities she experienced and witnessed in Tehran.

The Iranian Revolution erupted when Mohammadi was 10. Her father, who was in the military, was rarely around. Her mother, Rohparvar, a strong and independent-thinking nurse, raised her and her two older brothers alone.

“I use patterns of Persian gardens, rugs and tiles in all of my paintings to create in audiences the expectation of seeing scenes of joy, but I incorporate symbols of mortality and grief and sadness to reflect what has gone on in Iran in the past and what is happening now to challenge such expectations,” said Mohammadi, a married mother of two grown children who lives in Irvine.

“Maybe it’s fate that I had the opportunity to come here and take my art to the next level,” she said.

Accolades

In February, Mohammadi won a $5,000 grant from the arts-focused MOZAIC Philanthropy, which also included her oil-on-canvas work, “Untitled,” as well as “Persian Venus,” in a group exhibition. She also received from MOZAIC the first-ever Future Student Art Prize for the “2021 Future Art Awards: Ecosystem X.”

In summer, Mohammadi received a second-place award from a juried show at the Lancaster Museum of Art, which purchased her “Untitled” painting at the end of the show.

And just before Thanksgiving, she received word that another of her paintings, “Now Persian Garden,” was selected by jurors for the University of Montana’s online exhibition of graduate students’ work, “Here, There, and Nowhere.”

Fewer than 6% of submissions are accepted.

Juror Eric Jensen writes of Mohammadi’s work: “Many paintings are containers for memory. This piece is functioning in that way, yet it feels more like a memory that was chosen because the rest of them were too painful. It feels like if the scene moved to the left or right, we would be beholden to terrible violence.”

Added Jensen: “I think that she did an incredible job capturing an essence of (Iranian) history in such a stunning and magical piece.”

Freeing experience

Growing up, Mohammadi always liked art. She trained and worked as a professional artist in her home country. For many years, she worked with realistic master painters and had three solo shows in Iran. A book of her final show in the Iranian Artist Forum in Tehran was published in 2008.

It wasn’t until she came to Orange County that her painting took an entire new direction that freed her to express what she wanted.

Mohammadi, who earned a degree in chemistry from Azid University in Tehran, enrolled at Irvine Valley College to learn English. There, she took a live drawing class — something she never was allowed to do in Iran.

Studying the nude human form, Mohammadi learned about anatomy and proportion (in “Untitled,” her nude male figure is based on Michelangelo’s Renaissance masterpiece sculpture, “David”).

“He (Michelangelo) was brave enough to show his passion for the male body when homosexuality was an unforgivable sin,” she wrote in describing the symbolism in “Untitled.”

Such freedom of expression in Mohammadi’s painting proved revolutionary to her.

She tearfully recalls a female high school student in Iran who suddenly disappeared from class, never to be heard of again, after school authorities learned about her sexual orientation.

She recalls the bruises on some of her female friend’s faces.

At CSUF, which Mohammadi entered in 2018 after earning an undergraduate degree in studio art from UC Irvine, she painted a series of works whose theme was domestic violence.

Surviving, thriving

Drawing and painting professor and program coordinator Kyung Sun Cho, a member of Mohammadi’s MFA graduate committee, is impressed by her passion and commitment for painting.

“It has been a privilege to support her research and artistic development over the last few years,” Cho said. “In her work, she explores the complex history of Iran and her traumatic experience with oppression and gender discrimination.

“As an immigrant, her journey to make a new life in the U.S. is a powerful quintessential American story. It takes imagination and resilience to not only survive but thrive, and she is thriving.

“She’s making significant contributions to the Painting and the Arts Program with her work spotlighting advocacy for women … (and) her paintings can inspire important discourse in the classrooms. Her transformation as an artist and teacher has been remarkable.”

Freedom of expression

Of her experience at CSUF, Mohammadi said: “My work has changed drastically since I started my first semester here. I’m very thankful that I had the opportunity to work under the best professors and advisers. We have had many amazing critic classes, plus guest speakers and lecturers, that helped evolve the conceptual and technical aspects of my work.”

In remarks about her work “Untitled,” Mohammadi asks: “Why should minority groups suffer and be rejected in traditional religious societies? Their lives and their state of being are in serious danger.”

It’s a sentiment that is reflected, in some ways, in all her paintings — and an artistic direction she feels privileged to continue to explore.

“Painting has changed my life,” she said. “It’s something I deeply love and something I’m deeply committed to continue.”

Follow Mohammadi and her work on Instagram at @mahtab_painting

Related Articles

CSUF expands food-assistance program for students in need

‘Momentum’ to showcase work by CSUF dance students

Students test solar-powered sensors to detect early-stage wildfires

Day of Service at CSUF inspires students, faculty to give back

Titan panel discussion explores empowerment in Native American and Indigenous communities