I never considered myself a historian.

I never set out to be one, frankly. When you become a working journalist, you are consumed with the here and now, and you sometimes forget or gloss over the events that have led to the current path.

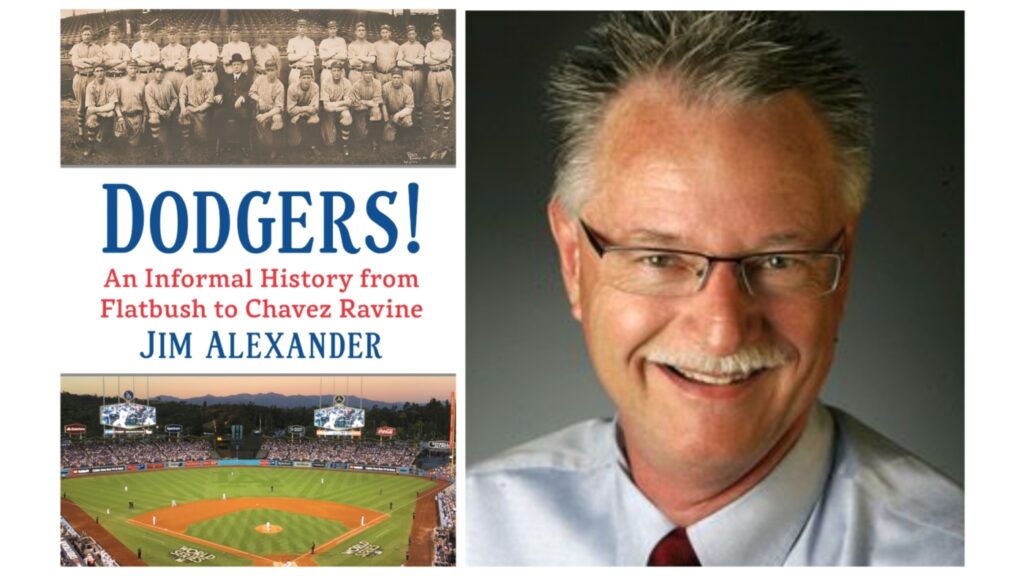

Yet as I researched and wrote my book about the Dodgers – “Dodgers: An Informal History From Flatbush to Chavez Ravine,” published by McFarland and Co. and released this past July – it was the past that consumed me.

The club’s recent history was relatively easy to chronicle. I had plenty of notebooks, scorebooks, saved interview notes and archived stories of my own from the last 4½ decades of the team’s residency in Los Angeles to work with. Earlier than that, in following the team and soaking up the impeccable storytelling of the late Vin Scully, it was impossible to not get a sense of the franchise’s rich legacy.

But as I dug further, beyond the Boys of Summer of the ’50s and the Daffiness Boys of the ’30s, the process was so darned fun that the more I discovered, the more intrigued I became about baseball in the 1880s and 1890s, the period in which the franchise’s roots were planted in Brooklyn.

As I said, I didn’t set out to chronicle history. I was tinkering with pitching a book of my past columns, but in going through my archives I found a trove of stories, columns and anecdotes about Tom Lasorda alone, and the thought occurred to me that there was potential here if I dug deeper.

So, blame Lasorda. (Lord knows I second-guessed him on enough other occasions.)

Who thinks about 1880s baseball, right? But when I started digging into it, I was fascinated. For instance, before 1883 pitchers were required to complete their deliveries with their pitching hand under their hips. The year that rule was changed was the same year a Brooklyn franchise entered the minor-league Interstate Base Ball Association, backed financially by a couple of casino owners.

(Given the way the sport has whipsawed from welcoming gambling interests to banning them, in the wake of the 1919 Black Sox scandal, to again welcoming partnerships with gaming companies in today’s climate, history does come full circle.)

In 1884, Brooklyn became big league by joining the American Association, which with the National League shared what was considered major-league status at the time. By 1889, then known as the Bridegrooms, they were league champions, and their manager, Bill McGunningle, had a reputation as an ace sign-stealer and was looking for ways to push the envelope. Sound familiar?

Or this: In 1890, when Brooklyn joined the National League and won a second consecutive pennant – and, again, didn’t win what was known then as the “World’s Series,” a portent of things to come, maybe – a breakaway group of players formed its own league for a year, fed up with how owners were treating them. So no, the modern Players Association didn’t invent labor unrest in baseball. It was there well before Marvin Miller came along in the 1960s.

Similar threads kept running through the history of the franchise that cycled through six nicknames (Atlantics, Grays, Bridegrooms, Grooms, Superbas and Robins) before settling on Dodgers – short for Trolley Dodgers – in 1932.

Researching and writing this book, which chronicles everything up through the end of the 2021 season, was a 2½-year process. A good portion of that was in the midst of the pandemic, a challenge from a research standpoint but not insurmountable. The final pages of the manuscript went to the publisher three days after the Dodgers were eliminated by the Atlanta Braves in October 2021.

(Had the 2022 Dodgers made a deep playoff run, I was prepared to plead for a second edition with an additional chapter. But we all know how that went.)

It was fun to discover the game as it was played in the 1880s and ’90s. The land acquisition process and construction of Ebbets Field was fascinating, as was the tidbit that owner Charlie Ebbets was convinced by a local sportswriter to name the park after himself. (Good luck making that argument today, when naming rights usually go to the highest bidder.)

There were the Hall of Fame careers of Zach Wheat and Dazzy Vance in the early part of the 20th century, the zaniness of Babe Herman and the 1930s clubs, the rebuild into what would ultimately become the Boys of Summer teams of the late ’40s and ’50s, and the transformation of the game and, to a degree, society itself with the signing of Jackie Robinson and the vanguard of great Black and Latin players.

Not insignificantly, there were ownership issues, economic stresses and unpaid bills through the years that would result in the team becoming the ward of the Brooklyn Trust Co. That led to Walter O’Malley’s growing presence and eventual control of the organization, and ultimately to the historic move to Los Angeles in 1958.

The team’s 65 years in L.A. alone represent a vivid history, with the construction of Dodger Stadium (and the controversy that preceded it), and the people who helped make the team not only popular but part of Southern California culture: Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale, Maury Wills, the Garvey-Lopes-Russell-Cey infield, Fernando Valenzuela, Orel Hershiser, Kirk Gibson, Hideo Nomo, Mike Piazza, all the way up to Clayton Kershaw, Justin Turner and the Dodgers of this era.

We’ve lost three of those unforgettable personalities in the past few months – Scully, the Dodgers’ indispensable figure in L.A.; Wills, who brought the stolen base back to the game and should be in the Hall of Fame; and Roz Wyman, the city councilwoman who played such a crucial role in persuading O’Malley that this would be the proper home for his team.

And the past 65 years have featured plenty of management and ownership follies of their own, the Fox and Frank McCourt eras providing severe contrasts to the way Walter and then Peter O’Malley did things. The current Guggenheim ownership has cleaned up McCourt’s mess and restored stability.

Then again, hard as it is to believe, maybe McCourt was an accidental visionary. When he took over, his feeling was that it was foolish to spend $150 million on payroll to win 98 games when you could win 90 and your division with half that. (To be fair, left unsaid in that attitude – read into the court record during divorce proceedings – was the idea that Frank and Jamie McCourt were using the team as their personal ATM.)

Related Articles

Alexander: Should Dodgers’ Winter Meetings inaction be concerning?

Dodgers sign former All-Star Jason Heyward to minor-league contract

Will the Dodgers go into 2023 without a designated closer?

Hoornstra: Baseball’s Winter Meetings produced more winners than losers

Dodgers-Carlos Correa speculation comes with heavy baggage

But consider: The 2022 Dodgers won 111 regular-season games with a $280.8 million opening-day payroll, but didn’t make it out of the divisional series while the third-place Phillies got to the World Series. Given their inactivity so far this winter, and the speculation that Andrew Friedman and staff are determined to get under the luxury tax threshold and reset their payroll, we could find out in 2023 if less is indeed more.

If it is, and if somehow the Dodgers turn 2023 into a magical year, maybe I can talk the folks at McFarland into that second edition after all.