Fiery Joshua Trees ablaze in a California wildfire create the striking cover image for “High Desert,” the new collection of poems by poet, editor and translator André Naffis-Sahely.

“A lot of the fire poems I wrote were around the 2019 fires when you’d get up in the morning and brush ash off the car, so I think it was almost a foregone conclusion that I’d end up writing about fires given what’s happened to our state the past few years,” says Naffis-Sahely. “I think of fire as this destructive force, but at the same time it’s always linked to the idea of rebirth, where, essentially, you can’t really have regeneration without fire, right?

Naffis-Sahely tells me there’s a British saying that poets don’t drive – “You and I both know that in the U.S. that’s not true at all. Poets definitely drive and they write a lot about driving.” – and that being behind the wheel exposed him to the California landscape’s beauty and its dangers.

André Naffis-Sahely is the author of the poetry collection “High Desert.” (Photo credit: Nina Subin / Courtesy of Bloodaxe Books)

“So as I’m writing this book, I’m driving for the first time in my life, I’m seeing fire everywhere,” he says. “The desert tends to be very brutal in the way that it destroys anything left behind by human beings, where it just completely wears down structures. The wind blows over and all traces of human activity are gone far more than in other kinds of ecosystems,” he says.

“It was also something that was quite fascinating to me, because one of the great differences between the Arabian desert that I grew up in, and the California desert that I spent so much time in, was the absence of fire, actually. Because fire is just not a thing over there,” says the poet. “We get sandstorms.”

Naffis-Sahely is talking to me, not from the desert, but from London where he spends part of the year as editor of the magazine Poetry London. Born in Italy to an Iranian father, an architect and activist who escaped the 1979 revolution, and an Italian mother, Naffis-Sahely grew up in Abu Dhabi before moving to the U.K. in his late teens. He says he might have stayed there had he not met his wife, the writer and educator Zinzi Clemmons, and moved to the U.S. in 2014.

Since then, he’s taught at Whittier College, Occidental College and was author in residence at UCLA, and when we talk he and Clemmons were preparing to return to California and their positions at UC Davis, where they both now teach. (And full disclosure: As I was preparing to interview Naffis-Sahely, I realized he and I had met once for a few minutes on the campus at Occidental College, something I’d been unaware of when I started reading his work.)

The poet’s decision to move to the United States to be with his wife fuels one of the collection’s most powerful poems, “Welcome to America.” Written in the voice of an immigration agent, the poem shares a litany of accusations and insinuations – “I’ve looked at your passport / and there are too many stamps,” “Why would she want you?” and “I like thrillers / and mysteries and plots with / a point” – that the poet says were said to him in real-life.

“The original title was, ‘What the Immigration Officer Told Me,’ because that’s essentially what happened. That poem is pretty much a direct transcript of a conversation I had during one of the many, many times I was grilled by airport security,” says Naffis-Sahely, who says the agent couldn’t believe the poet was moving to the States for love. “They actually did print out my poems and essays” in a vain attempt to try to find some other motive.

Joining his previously published collection “The Promised Land: Poems From Itinerant Life” and the pamphlet “The Other Side of Nowhere,” “High Desert,” which is out from the U.K. poetry publisher Bloodaxe Books, mixes work about Los Angeles and the California desert with found poems that evoke the voices of 19th Century scholars and labor activists along with figures like Gen. George S. Patton and Richard Nixon using their own words.

This isn’t Bisbee, but a scene from the cemetery at Bodie Historic State Park wooden buildings in infrared. (Getty Images)

One of the Los Angeles poems, “Maybe the People Don’t Want to Live and Let Live,” evokes the life of Arthur Lee, the leader of the great 1960s LA band Love.

“With Arthur Lee, as you know, there was so much of California, specifically LA, in his life. Through the course of his life, you really see LA kind of transformed from the place that it was in the ‘50s all the way up to the early noughties just before he died,” says the poet. “I love his music. The more I read about him, there isn’t as much as I’d like out there; I think people should write more books about Arthur Lee.”

In the poem, “At the Graves of Labour’s Fallen,” he describes a haunting visit to a cemetery in Bisbee, Arizona, where the best plots “belonged to cattle-thieves, cut-throats, bushwhackers” but tucked away in the back corner were the laborers and Labor organizers where “Time / had made most names illegible” on the headstones.

“When I was going through the graveyard, you’d see that the elements essentially had just rubbed away at the gravestones, to the point that you can barely make out the names,” he says. “Part of the fuel for these poems was, OK, you may not be able to capture the whole of what that moment was, the whole of what that existence was, but you’re able to put down at least a very limited record of it before it completely vanishes.”

Naffis-Sahely and I talked about a range of other topics – from the great California poet Robinson Jeffers to haunting stories about buildings eroded by sand and the elements – and as we wrapped up, I asked if there’s anything else he’d like to share about “High Desert.”

“You know, maybe, on the politics, I’ll say this: My father is Iranian; he left Iran in ‘79 because essentially he was a left-wing activist. And so like a lot of people in that kind of background, he was exiled. And so I think part of it was a bit of a tribute to him and to his brand of politics. You know, we’ve always had a bit of a tradition of left-wing politics in the family,” he says, adding the book was “my way of talking about family history, but in a different way.”

• • •

What novels or nonfiction are you enjoying? If you have any book recommendations, please send them to epedersen@scng.com and they might appear in the column.

Thanks, as always, for reading.

Craig Johnson reveals the book he considers ‘literary napalm’

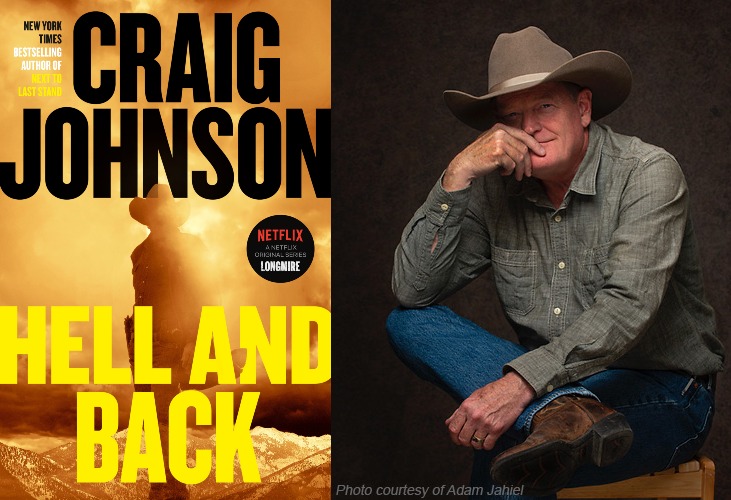

Craig Johnson is the author of the Longmire book series, of which “Hell and Back” is the latest. (Photo by Adam Jahiel / Courtesy of Viking)

Craig Johnson is the author of the best-selling Longmire mystery series, which has also been turned into a Netflix series. He lives in the town of Ucross, Wyoming, which has a population of 26. The latest Longmire novel, “Hell and Back,” is out this month.

Q. What can you tell readers about your new Longmire book, “Hell and Back”?

I think, after 18 Longmire novels, it was time to shake things up, and “Hell And Back” certainly does that. The good sheriff finds himself in the middle of a snow-covered street in Fort Pratt, Montana, a town infamous for the fiery deaths of 30 young Native boys in a local boarding school. Walt can’t remember who, what, or where he is, which sets him on a trajectory of investigation of himself before he can even attempt to discover why it is that he is there.

Q. This is your 18th Longmire novel. What are the challenges of writing a character over many books as you’ve done?

Any long-lived series demands a bit of reinvention from time to time, which is an adventure in itself, because you’re tampering with a formula of success, and some loyal readers may not appreciate that. I’m lucky in that I’ve got pretty sharp readers and a wonderful publisher in Viking/Penguin that allow me a great deal of literary freedom—so I get to take chances.

Q. What is the most unexpected benefit of your writing success?

I can walk into the hardware store in Buffalo, Wyoming and buy anything I need. Now, that might not sound like much, but for a guy who has straightened nails for most of his life, it’s pretty great…

Q. What are you reading now?

I’m reading David Maraniss’ biography of Jim Thorpe, “Path Lit By Lightning,” and Nathaniel Philbrick’s “Travels With George”—we’re so fortunate to live in a time when so many marvelous writers have turned their talents to non-fiction. I’ve also been lucky enough to snag an advance reader copy of T. Jefferson Parker’s upcoming “The Rescue,” always a treat.

Q. How do you decide what to read next?

Well, I’m an indentured servant in regard to researching the Longmire novels, which is a blast, but other than that I just follow my interests and good writers. There are really only two genres in literature, good writing and bad. I try to avoid the bad.

Q. Do you remember the first book that made an impact on you?

“To Kill A Mockingbird” set me back on my heels as a child – it’s literary napalm, it sticks and burns. Another would be “The Grapes Of Wrath,” which people are still trying to ban all over the place. I have to smile every time I visit the Steinbeck Center in Salinas, in that I’m acutely aware that in the ’30s they used to burn the man’s books right across the street in the town square.

Q. Is there a book you’re nervous to read?

The sequel to “To Kill A Mockingbird,” “Go Set A Watchman,” I can’t help but think that Harper Lee didn’t want that book published.

Q. Do you listen to audiobooks? If so, are there any titles or narrators you’d recommend?

Anything read by George Guidall – he’s the king of audiobooks. I live on a ranch where the nearest town has a population of 26, and when I feed the horses at night, I have an old CD player where I keep Guidall. As the horses eat, I sit there on a stool in the tack shed and have him introduce me to the literature of the world. I was once talking to him, and we discussed the importance of audio books, particularly in the American West, and how people rarely sit in their cars and finish an album, but they’ll sit there in a parking lot or their driveway and finish a chapter. Besides, he records my books…

Q. What’s something about your book that no one knows?

The horrific fire depicted in “Hell And Back” is actually modeled after the boarding school fire that took place in Wrightsville, Arkansas, in 1959, where 21 African-American boys were burned to death—doors were locked from the outside and some of the children were literally chained to radiators.

17 fall books

New books coming from Cormac McCarthy, Celeste Ng, N.K. Jemisin, more. READ MORE

Antoine Maillard’s debut graphic novel, “Slash Them All,” was influenced by classic horror films. (Photo courtesy of Fantagraphics Books)

Everything slashed

Antoine Maillard’s graphic novel, “Slash Them All,” was influenced by classic horror films. READ MORE

Talia Lakshmi Kolluri is the author of “What We Fed to the Manticore.” (Photo credit: Sarah Deragon / Courtesy of Tin House)

Making ‘Manticore’

Talia Lakshmi Kolluri describes writing from the point of view of animals. READ MORE

“Faiy Tale,” the latest novel by Stephen King, is among the top-selling fiction releases at Southern California’s independent bookstores. (Courtesy of Scribner)

The week’s bestsellers

The top-selling books at your local independent bookstores. READ MORE

Bookish.

What’s next on ‘Bookish’

The next free Bookish event is Friday, Oct. 21 with guests Anthony Doerr and more joining host Sandra Tsing Loh.

Sign up for The Book Pages

Miss last week’s newsletter? Find past editions here

Dive into all of our books coverage