Singer Linda Ronstadt initially thought her new book might be a collection of recipes from a trio of Tucson, Arizona families, including her own.

Her friend CC Goldwater, the granddaughter of the late Arizona senator and presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, came to her with the idea, suggesting it as a project they might do to raise money for research on Parkinson’s disease, which Ronstadt was diagnosed with years ago.

“So I say, ‘Well, I don’t cook. I’m famous for not cooking,’ ” Ronstadt says, laughing. “But we thought we’d try it anyway.”

Ronstadt wanted to include three families with deep roots in the Sonoran desert of Arizona: the Ronstadts, the Goldwaters, and the family of Bill Steen, Ronstadt’s longtime friend. The Steens and Ronstadts had connections that went all the way back to the 1800s.

Ronstadt invited the writer Lawrence Downes to be her co-author and Steen, an acclaimed photographer, to provide the art. They all took a trip across the border to research recipes they might include.

And then, with all those pieces in place, the project ran into reality, Ronstadt says.

“A cookbook wasn’t something that was wanted out there in the publishing world,” she says. “It just didn’t quite come together.”

Which nonetheless worked out just fine in the end.

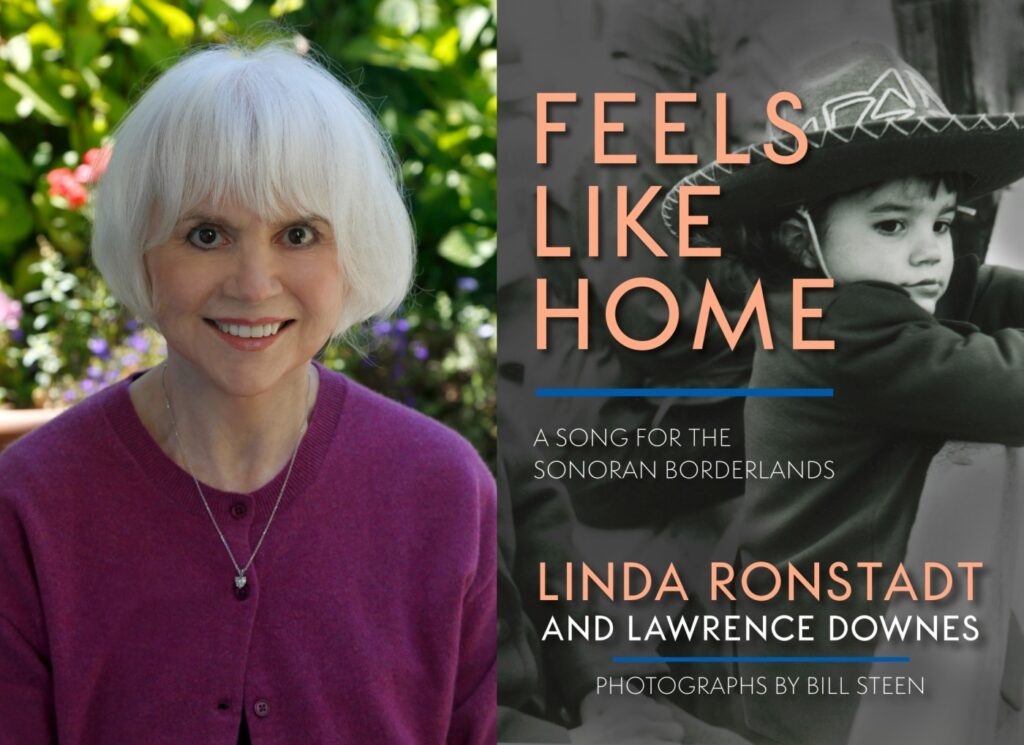

“Feels Like Home: A Song for the Sonoran Borderlands,” arrives Tuesday, Oct. 4, written by Ronstadt and Downes with photographs by Steen.

So while it does contain some recipes, most of them reaching back generations, it’s not really a cookbook. Instead, “Feels Like Home” is a memoir with food and a travel book about a handful of families. Ronstadt is at the book’s center, providing a deep understanding of what life was like for those hardy people who settled in the Sonoran desert many years ago, as well as the Indigenous people who lived there for centuries longer.

Tracing the roots

“I wanted to write it about a single region, which is the Sonoran Desert,” says Ronstadt, 76, from her home in the Bay Area. “It’s very much its own place like Patagonia. And it exists on both sides of the border, so it’s a both-sides-of-the-border story.

“That’s what the book came out of,” she says. “It was our running the road up and down.”

It also a deeper dive into the Ronstadt family history than she’d ever taken before.

With Downes’ research skills, she found letters in the Arizona Historical Society that her great-grandmother Magdalena Redondo Ronstadt wrote in the 1880s from her home on the Mexican side of the border to her son – Ronstadt’s grandfather Federico “Fred” Ronstadt – after he moved to Tucson at the age of 14 to apprentice in a carriage shop.

And later, the book shares Fred’s love letters to Ronstadt’s grandmother Lupe Dalton, full of passion and frustration at Lupe’s reluctance to return his feelings, though in time she did.

“I was so shocked because they were such an ideal couple,” Ronstadt says. “My grandmother lived to be 96. My grandfather lived to be 84 or 86. And they were very loving always and very considerate to each other and enjoyed their family.

“Boy, maybe she had some high school crush that she was hoping she wouldn’t have to marry him,” she says.

Food and family

Many of the recipes in the book will be familiar to anyone who’s lived in the Sonoran Desert or even eaten in Southwestern or Mexican restaurants in the region.

Many are simple dishes such as carne con chile or Sonoran enchiladas. Some are less so, such as El Minuto’s cheese crisps, Tepary beans, or albondigas de la Familia Ronstadt – Ronstadt Family Meatballs.

Food, she writes in the book, was always a way for families to spend time together and show love for each other. Especially on the daylong picnics her extended family often took, as was customary for most who lived there at the time.

Asked what she remembers most of those days, she says “the camaraderie, us around the fire.”

“You know, my Dad was cooking and my brother would be helping him,” Ronstadt says. “And my mom would be bringing beans and tortillas out from the kitchen. We had someone that lived in our house that made those beautiful big tortillas. They’re made by hand, they’re very labor intensive and they taste like nothing else.

“I grew up eating those kinds of tortillas,” she says. “And I think food is important in every culture. It’s central. It’s central to every culture. So that was our style.”

Desert beauty

Other chapters in the book explore her memories and the broader history of the desert and its people from the present to the far past, with photographs by Steen that capture in beautiful color a desert landscape little changed over time.

“It’s a ferocious beauty,” Ronstadt says of the desert. “My dad was very visually inclined, very inclined to visual art. He was a good singer, but he was really a good watercolorist. And he painted the desert all the time.

“He could see it, you know, and he’d point it out,” she says of the region’s natural beauty. “We grew up with that awareness of beauty. My mother would just run outside and look at the mountains when it was sunset and the mountains all turned pink. It was quite a show.

“We grew up taking it for granted, but we loved it,” Ronstadt says. “Just like I feel the same way about water. We had a well on our property. We had real sweet water. And I remember sticking my face in the irrigation ditch and it was cold, and I thought, I’m gonna miss this someday.

“And boy, do I miss it living in California in the drought,” she says.

Desert without borders

People lived in the Sonoran Desert long before there was a border drawn to separate the United States from Mexico, a point Ronstadt emphasizes by tracing her family’s history on both sides of that manmade line.

“The desert is beautiful until it has fascist geometry put on it,” Ronstadt says. “Nature hates perfect geometry. It likes random asymmetry. So the day you start putting fences in and building in a straight line a desert turns into a wasteland.”

Born in Tucson in 1946, Ronstadt remembers how little the border mattered on trips between countries when she was a child.

“We used to drive to the border town, which takes about an hour,” she says. “We’re used to go down and shop and have lunch and just drive back home. It was like driving to the beach in Los Angeles if you lived in Hollywood.

“We knew the people down there,” Ronstadt says. “We knew their families. We knew the ranches. My dad knew the ranchers because he sold equipment to them.

“It was a real hospitality like nothing else, and it wasn’t a big deal,” she says. “To get back across, it didn’t take hours. Now, it’s just a nightmare. You go across the border you might as well plan to stay the night because you’re going to be half the day the next day getting back.”

The fence that the United States has built along stretches of its Southern border prompts disdain for its interruption of the landscape and its impact on all living creatures who cross it.

“The fence is a joke because people cut through the fence, they dig under the fence,” Ronstadt says. “And most people who come in (illegally) come in on planes legally and then they overstay their visa.

“It’s not doing anything to help the immigration problem except make criminals out of children that they take away from their families. Do such trauma to them that God knows how they’re gonna survive.”

Mas canciones: more songs

There is music throughout the chapters as befits a book written by a singer who is in the Rock Hall of Fame but has also been honored by institutions as varied as the Academy of Country Music and the Latin Grammys for her work in those genres.

A musical soundtrack to the book, “Feels Like Home: Songs from the Sonoran Borderlands—Linda Ronstadt’s Musical Odyssey,” will be released by the Putamayo record label on Friday, Sept. 30.

But the book also includes a final chapter with a do-it-yourself playlist with categories such as Songs We Ronstadts Loved and Sang or Songs of Mexico and the Borderlands.

“There were some that I remember from earliest childhood on,” Ronstadt says of the songs she presents in this chapter, each with a short description of how it connected with her, her family, friends or the region.

“A trio style that my sister and brother used to sing,” she says. “I recorded some of it on the second album, ‘Mas Canciones,’ that I made. I included two trios by me and my two brothers. They were just some that we loved.”

Ronstadt last sang in public in 2009, the effects of her illness depriving her of the clear, beautiful voice loved by many. Still, there are memories in the songs that exist, and those she writes about here.

“You remember all the times you sat together and sang them,” she says. “When you were 14, when you’re 18, and when you were 50.

“And now we’re all geezers, you know, and we can’t sing anymore,” she says, and laughs.

Related Articles

Namwali Serpell describes how she explored loss and grief in ‘The Furrows’

24 years later, Hua Hsu recounts an unlikely friendship and its tragic end

The Book Pages: It’s Banned Books Week, and here’s what the library is doing

Author Ling Ma says she let ‘anxiety lead me’ while writing ‘Bliss Montage’

Why Scott Turow made an ‘audacious’ choice for his new thriller ‘Suspect’

Related Articles

Namwali Serpell describes how she explored loss and grief in ‘The Furrows’

24 years later, Hua Hsu recounts an unlikely friendship and its tragic end

The Book Pages: It’s Banned Books Week, and here’s what the library is doing

Author Ling Ma says she let ‘anxiety lead me’ while writing ‘Bliss Montage’

Why Scott Turow made an ‘audacious’ choice for his new thriller ‘Suspect’