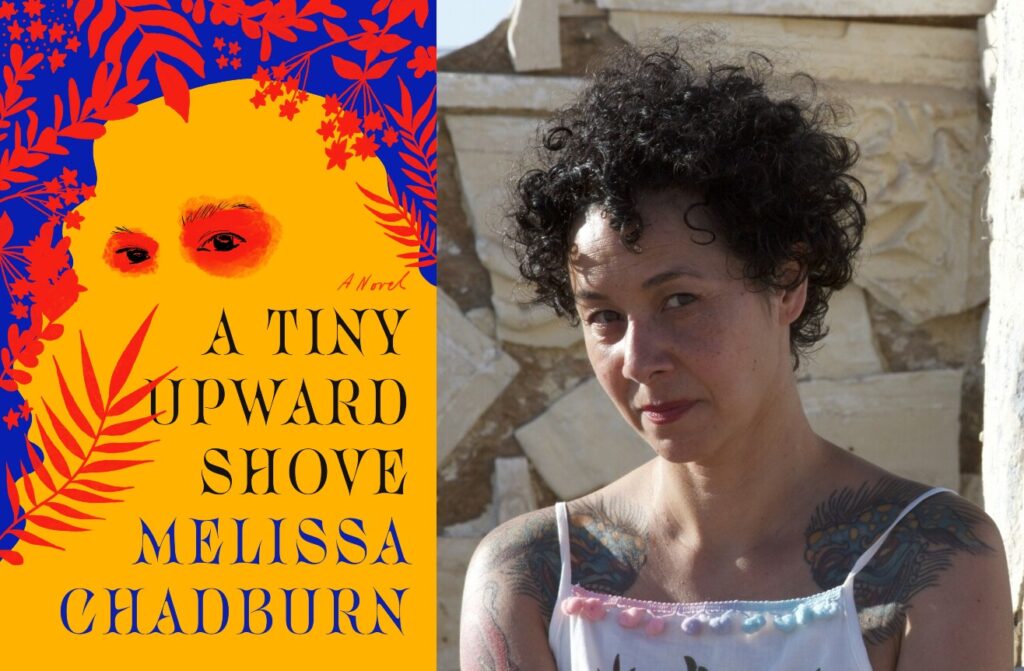

You could boil the plot of “A Tiny Upward Shove” down to this: It’s about a murdered young woman who transforms into a supernatural being to exact revenge on her killer. But this synopsis tells you next to nothing about all the levels of meaning within the complex debut novel by Melissa Chadburn, nor its kaleidoscope of poetic language and raw imagery. Its power must be experienced on the page.

“A Tiny, Upward Shove” feels like a novel only Chadburn could write, combining her unique history and education: She is a Ph.D. candidate in creative writing at the University of Southern California with an impressive list of published articles, many of which pull from her experience growing up poor in the foster care system.

More: Want stories on books, authors and bestsellers? Get the free Book Pages newsletter

The book has garnered wide critical praise: Hector Tobar, author of “The Barbarian Nurseries,” called Chadburn a “fiercely original, brave writer” who “finds the lyrical and the deeply human in seemingly dark and impenetrable landscapes.”

Chadburn, who was a recent guest on Southern California News Group’s Bookish video series, answered questions via email about her novel and her writing progress.

Q. Some readers might know you from your nonfiction. You’ve also been a longtime advocate for social justice issues and economic equality. Please talk a little about how this move into fiction fits into the work you’ve done thus far. How, for you, might fiction allow for a different kind of truth to be told?

This is a great question. I knew my larger project would always trouble our ideas of justice. Because I work in so many different genres, whenever I approach a new piece I often find that early part of writing container hunting. That is, finding the right container for the piece. In this case, I wanted to tell a WHOLE story, unbound by the limitations of, say, the both-sidism in journalism. Fiction allowed me to bring in magic and memory.

Q. Filipino culture, language and folklore are intricately woven into the storytelling of “A Tiny, Upward Shove.” Our primary narrator in fact is the supernatural being, an aswang, which inhabits Marina, a young woman who is murdered. I’m curious about much of this folklore you grew up knowing, how much research about it informed you, and how much license you gave yourself to merely invent.

My lola’s (grandmother’s) version of the aswang was a punishing aswang, ‘If you misbehave, the Aswang will get you.’ The aswang is mostly rumored to be a creature who flies onto rooftops at night with a long thin proboscis, with which she sucks up little babies. But as the novel states, depending on which province you’re from you can have a completely different concept of the aswang. She has different names, different ways of presenting: a vampire, a werewoman, a spinster. This gave me the comfort and creative confidence to supplement with my own interpretation. Which is that she is merely a misunderstood transpacific intersectional feminist.

Q. Murder, specifically the brutal murder of women, is central to the storyline, but not in the way that true crime narratives and popular fiction narratives often portray it. The women of your novel are portrayed as complicated, contradictory, and complex, not just as sainted victims. Why was this important to you?

The truth is the most interesting story, but the truth is complicated. It was also important for me to push against the common tropes of popular true crime narratives: The body. A white woman. The arbiter of justice, some carceral figure, a detective, a cop. I did take a small detour on my get-rich-slow path to writing and studied law for a bit, and I was always fascinated with this concept in law of making one whole. That if you’ve been wronged, it’s the function of the court and the lawsuit to make you whole. How can one be made whole after they say lose a loved one? Also, how does incarceration of one person make the other person whole?

Q. You based the serial killer in the story on a real-life convicted murderer, Robert “Willy” Pickton, who had been a pig farmer in Canada. What about him, in particular, interested you?

I just thought it was likely that at the time Marina emancipated from foster care (in the mid-’90s) that it would be likely that she would find herself being confronted with economic and physical violence but also engaging with sex work. Which could then place her on the Lougheed Highway – a highway that runs from the Pacific Northwest to Canada where there was a nexus of activity at the time. Multiple serial killers who preyed upon women, particularly women of color, Indigenous women, and drug-addicted women who were sex workers. This opened up the possibility to talk about these things.

Q, Writers know the Robert Frost quote, “No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader.” Did your book make you cry as you were writing it?

Maybe in the earliest pages, I cried. Let’s not forget I’ve been working on this book for seven years so some of these words have worked their way so far into my DNA, it would be hard to be surprised by any of them. Actually, no that’s wrong. The other day I read a passage and hearing the words aloud at that time, they struck me and I cried then, at the reading. It was when Lola Virgie visited Marina in the group home. I miss my grandmother and I wonder what she would’ve made of this book. She was feisty like the lola in this book but probably would not like all the curse words.

Q. The lush language of the novel and the frequent use of interior monologue brought to mind the works of Toni Morrison, Kate Braverman…even Virginia Woolf. What are some books and writers you’ve looked to for inspiration?

What an incredible compliment. Yes, Morrison definitely. “Beloved,” in particular. I read “Beloved” often, and am reading it again right now for my dissertation. Memory and intergenerational trauma are obsessions of mine. For language, I also read tons of Joyce Carol Oates. I think I have many of the same tics as Joyce Carol Oates: I italicize and underline certain words for emphasis. Structurally, I took apart and looked at a lot of novels, the first one that I had plastered all over my rented room in Iowa was Truman Capote’s “In Cold Blood.”

Related Articles

The Book Pages: Reading Louise Erdrich during difficult times

‘Hollywood Bowl: The First 100 Years’ book celebrates the history of the Los Angeles landmark

Long Beach swimming legend Lynne Cox writes about water rescue dogs in new book

This week’s bestsellers at Southern California’s independent bookstores

Novelist Emma Straub talks ‘This Time Tomorrow,’ time travel and father Peter Straub

Q. You thank many people in your book’s acknowledgments, which reminded me how much writing is not only a solitary act but something that creates community if we let it. Can you talk about the support others offered you in the process of writing, and what you learned while writing your debut novel?

Yes, I’m so lucky to have this loving supportive village, also, as I mentioned previously, I was in revisions for a really long time which meant that I was running all over town hawking my wares as an adjunct, or freelancer, and doing what I could to pay the bills. I often felt, (and still sometimes feel), that large swell of insecurity and it was so uncomfortable that I would reach for an external solution. Maybe if I hired this consultant or went to this workshop or somehow found myself in close proximity to the right person, they would advise me on how to write this book.

Like Marina, my protagonist, I grew up in foster care, and so I’ve spent much of my life, shucking and jiving in a way, trying to be who I thought people wanted me to be and I think I did the same thing with the book. To my editor’s bewilderment, with each revision I’d turn in a completely different novel. The greatest lesson I’ve learned is how important it is to sit in the discomfort, to be still, and silent, and try to tune into your gut, which I guess is done in solitude, but would in no way be possible without having people like my incredible, loving partner and wife. There’s also the reality of our external worlds, such as work and how to pay the bills, and care for the dogs, and wash the dishes or do the laundry and all of that can really only be accomplished in community.

Q. What haven’t I asked you that you’d really like to say to readers?

I’m so glad you asked. I do think that there are many breakdowns within our child welfare system, and while I don’t think there is one simple solution I do often consider Bryan Stevenson’s quote, “The opposite of poverty isn’t wealth. The opposite of poverty is justice.” I’m very excited by all the current guaranteed income projects, particularly locally here the work of The Compton Pledge. In my well-researched and reported opinion, the solution lies in a universal basic income, long-term affordable housing, equitable access to affordable healthcare, universal childcare, an affordable equitable education, and good jobs.