Leila Mottley will turn 20 this month. Like most kids her age, she has her hobbies (swimming laps and pole dancing and hanging with friends in Oakland), she has her passions (she was the city’s Youth Poet Laureate and has marched and protested for social justice) and she has her struggles (she attended Smith College but found the culture shock of a rural East Coast college to be too much).

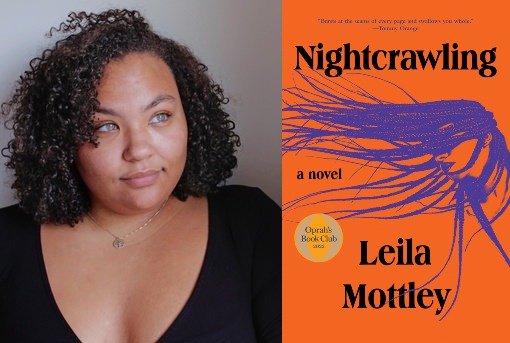

Unlike most 20-year-olds, however, Mottley is publishing her first novel, “Nightcrawling,” a beautifully written yet unflinching novel about growing up poor and Black in Oakland. Unlike most writers of any age, Mottley’s novel has just been chosen by Oprah Winfrey for Oprah’s Book Club.

Related: Get our free newsletter about books, bestsellers, authors, and more

The novel follows a girl named Kiara, who is on the edge of 18 and whose family has been riven by tragedy. Both her parents are gone and her older brother Marcus is too caught up in his rapping ambitions to help or even see clearly. Kiara is struggling to keep them from losing their apartment while also trying to rescue Trevor, the young boy next door whose mother is lost to drugs.

And that, actually, is just when things start getting really bad. Kiara, whose high school career was derailed by her turbulent home life, can’t find a job and falls into prostitution…which only gets worse when the police coerce the underage girl into performing sexually for them, frequently at their private parties.

That last part is based on a real scandal that shocked Oakland when it exploded in the news back in 2015 after one officer committed suicide and confessed what they had done in the note he left behind.

Mottley who wrote a long novella at 14 and a historical novel the next year – “I will never let anyone read them; they were practice” – followed the case closely. She began thinking about Kiara and her struggles and then when started writing this novel just before turning 17, she realized the police scandal fit well in the story she was telling about the obstacles facing poor, Black girls in America today.

Mottley spoke recently by video about her experience writing the book and what she hopes readers will take away from this bleak story. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q. Did you do research into the scandal?

I followed it very closely when it happened, and I went back and read transcripts and watched interviews with the young girl involved just to get a sense of her perspective. I also researched other cases of police sexual violence looking for narratives from survivors – but that’s not usually the way the media covers these cases, which is part of the problem.

Ultimately, I really didn’t want to interfere with the story because it is fiction, not a representation of the case. I had a foundation of knowledge, but I didn’t want true facts of different cases bleeding into the book. I wanted to create this character who would have narrative agency.

Q. Everyone harshly judges Kiara for what she has done but she tries not to and you clearly avoid passing judgment.

The world will find something to critique young Black girls about no matter what we do. I wanted to show the ways even in which the people who love her will find something wrong with the choices she made when she’s backed into a corner. I wanted to show how this happens and the ways in which the system created conditions in which she had very little choice.

Other people fault her but she knows there wasn’t another option. I wanted to show sex work without it being a critique or an admonishment. We are all trying to survive in whatever ways we can.

Q. At the start, Kiara has a tough life but she also has love and hope. Then the book gets darker and darker. Were you determined not to let readers off easy?

It was something I felt very strongly about. Going into the auction and talking to editors, I said the one thing I refuse to do is alter the ending. It’s important to me to tell the truth.

I try not to think of the reader – the minute you do it becomes hard to tell the truth. I let it get as dark as it had to and let the ending be what it had to be.

But while there are a lot of dark and cruel things done to Kiara, she has these glimmers, moments sprinkled throughout where I wanted readers to see that people are more than the worst things that happen to them. Kiara has this whole world and it’s not all centered on the bad things that happen to her, even as they get worse and worse.

Q. Do you hope to spark readers to action over the issues in the book?

I hope it has an impact on the way we think about policing and police violence and who we owe protection to. I hope we pay more attention to how we decenter Black women. And the ways we’re complicit. There were many people surrounding Kiara and Trevor who could have done more to protect them, to protect Black kids’ childhoods. It’s not just the scandal: It’s about housing, job insecurity, access to basic care. I hope all that is part of the conversation.

But while I know people want an actionable item list, that is complicated. I think we get so focused on conceptual ramifications of issues like police violence that we don’t think about the real impact on people. Novels allow us to look at people and to think of them as whole beings with lives as intricate and complex as ours. If readers come away thinking they need to go do something that’s good, but what lasts is the impact of loving a character and feeling compassion for their hurt.

Q. How much did being a poet influence your writing? Did you ever have to rein in your imagery?

Poetry is the foundation for how I write. I focus on rhythm and cadence and the ways I can shift language and make it more interesting. While I was writing, I was so immersed in poetry it definitely bled into the way this was written. Sometimes in the editing process, I’d say, “That was three pages of poetry but it made no sense for the story.” Even now I’ll read the book and find things that shouldn’t have been there.

Related Articles

The Book Pages: Reyna Grande shares the books she loves (and one she didn’t)

What Michelle Huneven’s novel ‘Search’ says about religion, recipes and Southern California

Novelist Nina LaCour explores California from LA and Long Beach to Bay Area in ‘Yerba Buena’

Melissa Chadburn describes mixing Filipino folklore, murder and more in ‘A Tiny Upward Shove’

This week’s bestsellers at Southern California’s independent bookstores

Q. Did writing a novel change your poetry?

Yes, I started writing more prose poems. It wasn’t what I wanted to do, but it was what was coming out. I had to intentionally disconnect the two to write the poetry I wanted to write. I try not to write poetry on the same day I write fiction. Also, when writing fiction I revise so deeply, and now I’m doing that more with my poetry.

Q. Will writing be harder now that there’ll be high expectations and an actual audience of readers awaiting your work?

It’s the worst thing now knowing people will read the next one. It’s a challenge to not think about readers and markets and everything. I understand the sophomore slump now.

I have actually written two other books since this one. The first just wasn’t quite right. I spent many months trying to revise it, but it needs more time. I intend to go back to it but probably in a few years. The second one I wrote in one month. I had this idea that I needed to switch to third person, which I think a lot of novelists do after their debut. People read it and said, “It’s a good book but it doesn’t sound like you.”

I had to detach myself from the idea that first person can’t be literary or beautiful. I love first person and now I’ve gone back to it and I’m in the middle of a new book and I think this one will make it.