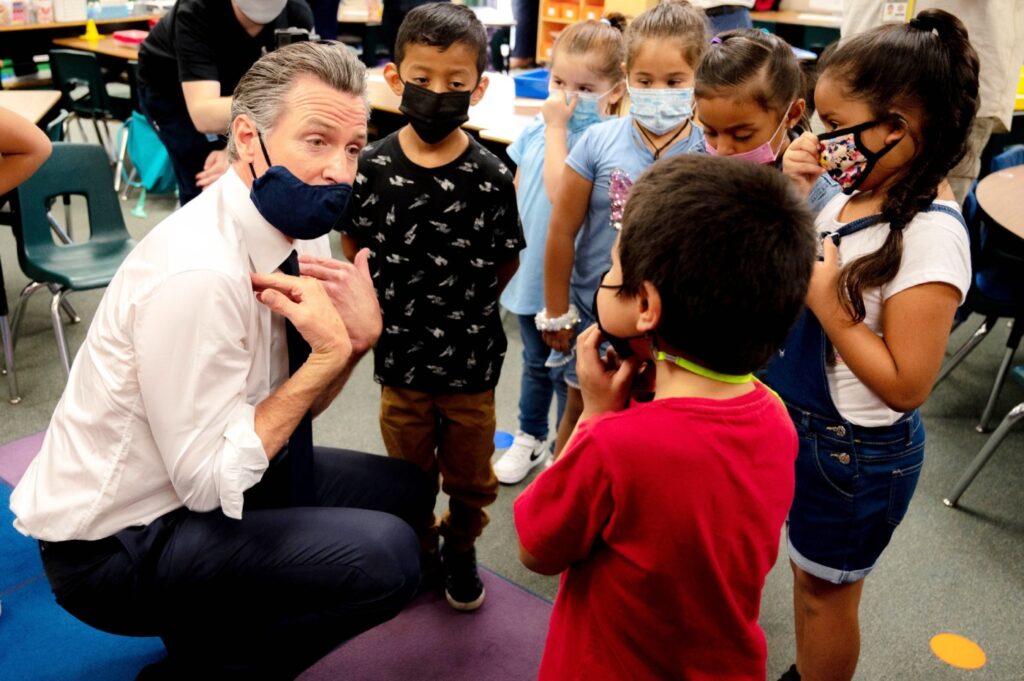

When Gov. Gavin Newsom unveiled his revised state budget last month, he boasted about increasing public school spending to $128.3 billion or nearly $23,000 per pupil with a goal of “completely reimagining the education system.”

What does that mean?

Newsom envisions universal access to pre-kindergarten care and education and transforming neighborhood schools into “community schools” that “partner with education, county, and nonprofit entities to provide integrated health, mental health, and social services alongside high-quality, supportive instruction, with a strong focus on community, family, and student engagement.”

The budget describes the “California for All Kids” plan as “a whole-child support framework designed to target inequities in educational outcomes among students from different demographic backgrounds, and empower parents and families with more options and more services.”

Its promise of integrated services mirrors another Newsom program to overhaul Medi-Cal, the state’s system of health care for the poor that serves a third of the state’s population. The new approach, dubbed “CalAIM,” would “move the whole person care approach that integrates health care and other social determinants of health, to a statewide level with a clear focus on improving health and reducing health disparities and inequities, including improving and expanding behavioral health care.”

Medi-Cal providers would not only be responsible for medical services but helping clients with other aspects of their lives, such as housing and income support.

Universal pre-kindergarten, community schools and CalAIM, if fully implemented as imagined, would move California toward more comprehensive — or perhaps intrusive — involvement in the lives of the roughly 14 million Californians who live in poverty or near-poverty with the goal of improving their lives and perhaps breaking the cycle of poverty. The interventionist approach also extends to another Newsom initiative called “care courts” that would compel mentally ill homeless people to undergo treatment.

They are experiments in social engineering that conceptually mimic Western Europe’s tradition of cradle-to-grave services.

The new vision’s education component might be the most difficult to implement because of schools’ historic focus on classroom instruction and the money to deliver it. Getting kids through 12 years of schooling is difficult enough, educators might say, without saddling them with responsibility for their families.

However, it’s unmistakably clear that California’s schools are plagued with a stubborn “achievement gap” separating poor and English-learner students from their more privileged peers, one that surely widened during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A decade ago, then-Gov. Jerry Brown persuaded the Legislature to take a different approach by reforming the school finance system to give more money to school systems with large numbers of students at risk of academic failure.

Newsom’s new budget builds on the concept by requiring local schools systems, beginning next year “to offer expanded learning opportunities to all low-income students, English language learners, and youth in foster care…”

So, one might wonder, what would it really take for the 60% of students who fall into those “high needs” categories to catch up with the 40% who flourish in the public schools?

Related Articles

‘Corporate-free’ Alex Lee benefits from corporate political spending

Joe Biden’s magical thinking on the economy has to stop

The history of the individual right to keep and bear arms

The problem with the California state treasurer race

AB 2840 will only make logistics worse in California, nation

Would integrating education with family-oriented social and health services do the trick? Or would it take billions more dollars on top of the budget’s $128.3 billion?

The Public Policy Institute of California recently released a report on that question, summarizing the many academic studies of the relationship between money and educational achievement. Generally, it concluded, more spending does have positive educational impacts, but closing California’s achievement gap could cost as much as $10,000 more per pupil each year.

That would boost current spending by nearly 50% and cost up to $60 billion a year, probably a politically impossible amount.

CalMatters is a public interest journalism venture committed to explaining how California’s state Capitol works and why it matters. For more stories by Dan Walters, go to calmatters.org/commentary.