My book “Trace: Memory, History, Race, and the American Land” (Counterpoint Press) began as a struggle to come to terms with questions that have lingered since my childhood — about my origins, about my place, about what it means to inhabit this land and to be a citizen of this nation.

Early on, the mountains, coast, and quality of light of Southern California imprinted on me, the only child of older parents who had migrated westward, my father searching for opportunity, my mother following without much question.

I, though, had questions.

I grew up in a family largely silent about its past: How my ancestors — from Africa, from Europe, and from Indigenous America — converged in me seemed beyond reach. Even though, as an Earth historian, I could track the continent’s deep past from rocks and fossils, the traces of my own family’s generations seemed eroded and lost.

Was my family’s past lost to the ages? I wondered if my work reading the land’s history could help me fathom a human past on the land, so I’d like to tell you a little about my path to understanding.

Devil’s Punchbowl in Angeles National Forest (Getty Images)

Sand and stone are Earth’s memory. Each of us, too, is a landscape inscribed by memory and by loss. At a young age, I began to hope that despite such wounds a sense of wholeness could endure. That each of us might possess a hardness — not harshness, not severity, but the quality of stone or sand to retain some core though broken again and again.

This internal struggle led me on many journeys across a continent and time to understand how the country’s ever-unfolding history has marked the land, this society, and a person: The twisted terrain within the San Andreas Fault Zone. The Grand Canyon’s rim. A South Carolina plantation. An island in Lake Superior. “Indian Territory” and Black towns in Oklahoma. The U.S.-Mexico Border and U.S. capital. National parks, burial grounds, and even the names this land wears.

Once, on a journey to the Devil’s Punchbowl in the San Gabriel Mountains, I began to see how the structure, materials, textures, and history of Southern California’s rugged landscapes offered metaphors to ponder the deposition and erosion of human memory, the fragmentation and displacement of human experience.

In my book “Trace,” I write about this ancient yet dynamic landscape near the San Gabriel Mountains and its lessons for a searching soul:

Steeply tilted sandstone ledges hundreds of feet high rim the Punchbowl, a “geologic curiosity” within the San Andreas Fault zone. Fluent and patient in its work, the small stream draining the rocky bowl gathers and reworks pieces of the cliffs and abutting San Gabriel Mountains, today as it has done through centuries of days. It is a tactile reminder that here is a land of process and response. Water’s motive forces from cloud to creek — the forces of weathering and erosion — and abrasive, shuddering movements along bounding faults shaped and continue to reshape the cliffs and basin. What one might perceive as timeless is but one frame of an endless geologic film.

I descended through stands of pinyon, manzanita, and mountain mahogany to wade the cooling water. To watch grain after entrained sand grain roll, bounce, and be carried aloft. Long-avoided questions emerged as the current nudged me downstream with its sediment. I was five years old when last at the Devil’s Punchbowl, on a picnic with my mother and father. Decades later the cliffs and basin still fit within memory’s frame, satisfying a wish to feel sun-warmed sandstone and this stream’s grainy flow. But perhaps I also returned to reach beyond memory to some origin, to some direction. That five-year-old had imagined these waters flowed from the beginning of the world. . . .

The San Gabriel Mountains rise to ten thousand feet, jutting high above Los Angeles and the Mojave Desert. Between peaks and city basin lies the sharp turning hinge of a geologic trap door hidden by alluvium, freeways, and sprawl. These mountains continue to lift at rates among the fastest on the continent. But as they grow they weather away, grain by grain, the residue carried downward to spread around their base like a fallen skirt. The daily business here is uplift and erosion, mountain making and decay.

The nearby Devil’s Punchbowl consists of sandstone and conglomerate, once sands and pebbles of ancient mountain streams that flowed millions of years ago, now upended into rocky tablets.

What to take from this?

Each grain, each pebble embedded in Punchbowl rock, began as detritus from the denuding of ancestral highlands. Now-vanished cascades once conveyed sand and gravel down now-vanished mountains. If you and I were to examine the pieces, consider their texture and makeup, we could deduce much about their places of origin, about climate through time. But the Punchbowl as a place of tilted rock also means later shifting and deforming. Earthquake after earthquake dragged and shoved this terrain against the San Gabriel Mountains like a crumpled carpet shoved into a wall.

Origin and material source. Warping displacement. We can still detect both kinds of provenance even though most of what once existed long since eroded away.

What of us? What of who we are is owed to memories of blood or culture, custom or circumstance? To hardness? What makes an individual in a sequence of generations?

These questions simmered on my drive east from the Punchbowl. June edged toward its longest days as I followed Pacific-bound streams to their source, then across the Continental Divide. It did seem easier to piece together the geologic history of almost any place on Earth than to recover my ancestors’ past. Easier to construct a plausible narrative of a long-gone mountain range from the remnant pieces than to recognize the braiding of generations into a family. Than to know my parents’ reasons for turns taken.

• • •

The past-to-present that we all emerge from is broken and pitted by gaps, not unlike the fragmented annals of Earth history. For me, these gaps grew from many things. From centuries of omissions and erasures. From losses of language and voice. From dispossession and forced servitude. From complex dimensions of lives flattened and distorted by the weight of ignorance and stereotype. From public narratives that still dis-member who “we the people” are to each other and to this land.

Related Articles

The Book Pages: Kim Stanley Robinson shares the books he loves — and a story that improved with age

Head back to ‘The Office’ as Jenna Fischer and Angela Kinsey write about the series, friendship

This Stanford lecturer discusses time travel, psychedelics and debut novel ‘The Red Arrow’

This week’s bestsellers at Southern California’s independent bookstores

Novelist Benjamin Myers talks crop circles and climate change in ‘The Perfect Golden Circle’

And for you? What of your own life, the lives of your family? I ask each of you, please, to think about your own origins and ancestors, to ponder your relationships with the past to present on this land. Our stories will differ — yet this richness of experience is so vital to understanding who we are.

Recognizing the nature of, and reasons behind, silences and gaps is as important as gathering the pieces found. In “Trace,” I begin this reckoning to re-member.

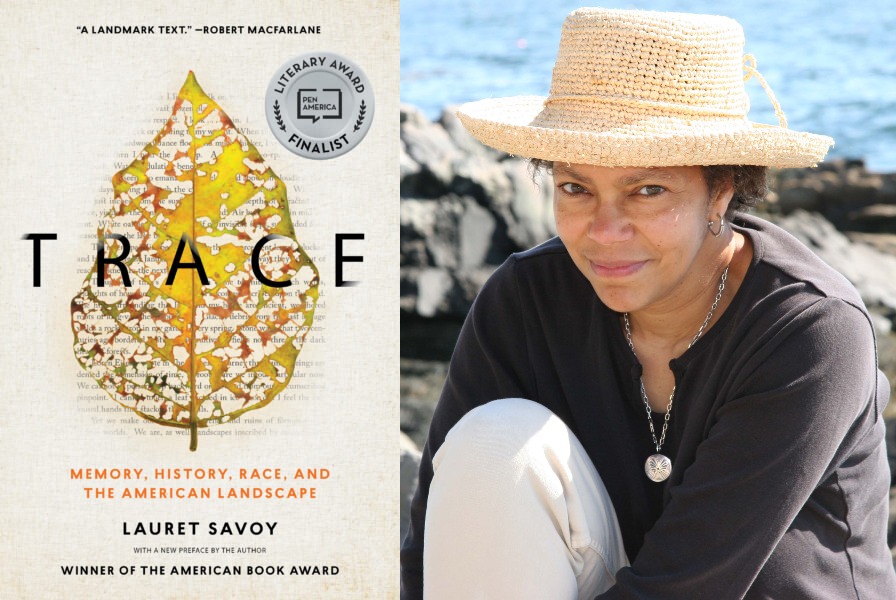

Lauret Savoy is a writer and the David B. Truman Professor of Environmental Studies and Geology at Mount Holyoke College. “Trace” won the American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation and the ASLE Creative Writing Award. It was also a finalist for a PEN American Award and Phillis Wheatley Book Award, as well as shortlisted for the William Saroyan International Prize for Writing and Orion Book Award.