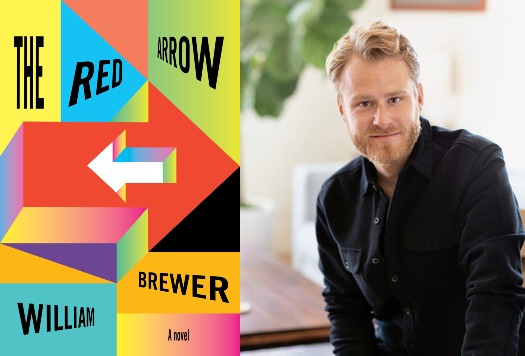

“I want to say, first of all, that I am happy,” is the first thing the narrator of William Brewer’s debut novel, “The Red Arrow,” tells us. Then he settles into a train and begins traveling both forward and backward in time.

His physical self is racing north through the Italian countryside toward The Physicist, an enigmatic and elusive man who holds the key to the narrator’s personal future — he has disappeared in the midst of a writing project, leaving the narrator’s career and bank account in peril — as well as humanity’s understanding of the future and the past.

Meanwhile, the narrator’s mind is propelled back into the past, to the traumas of his West Virginia childhood, to his home state’s environmental degradation, to his successes and failures as a painter and writer, and to his relationship with Annie, now his new bride. As it circles in and around these events, the narrator places us in the thick of The Mist, the pervasive depression that, for decades, hung over his every thought and every move. Ultimately, we plunge forward in time to meet The Physicist while also gaining a deeper understanding of the radical psychedelic therapy that transformed the narrator’s life, lifting the shroud from his soul.

Brewer, a West Virginia native and award-winning poet, says he liked setting the character on the train because “it would imbue the book with a sense of motion and speed. I like stuff with a sense of propulsion – I’m a fan of punk rock.”

Now a lecturer at Stanford University, Brewer, 33, saw that the train worked to illuminate “our relational experience with time – we can be ripping up the peninsula of Italy but in our minds we are way back in our past. We exist in both places simultaneously.”

Brewer spoke recently by video about his own depression, perceptions of his home state and the impact of psychedelic therapy. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q. The book covers a lot of topics and themes. What was the impetus?

All I had at the beginning was, “What if there was a guy on a train going to talk to a physicist?” I asked my wife if she would read a book about that, but we were getting ready to go to the airport to pick up my mother-in-law and she said, “Yeah, whatever. We gotta go get my mom.” But that was enough.

That was like a splinter caught in the brain and just sat there. Then time went by and in real life I had an experience with psychedelic therapy and that set the ball rolling. From there I just wrote it one page at a time, which would show me the next thing to do. I rarely ever have a plan. I firmly believe that things tend to emerge. When you try cooking up a scheme it feels contrived so I never sat down and said I’m going to hit those topics.

Through practices like meditation and through psychedelics I’ve learned a lot about consciousness. The brain is trying to find patterns and build a story to make sense of what we call experience, so I leaned into the process.

And we were on time to get my mother-in-law. I’m very punctual.

Q. The book circles back and forth as though your narrator was [“Slaughterhouse-Five” protagonist] Billy Pilgrim unstuck in time but only in the mundane and miserable parts of his life. This ties into The Physicist’s ideas but why tell the story that way?

I lived with depression for a really long time. It’s a disease where you’ve lost control of the narrative of your life. This thing is telling you the story of your life in a really deranged way, you can’t escape and eventually get lost inside that. The book is trying to inhabit an alternative form of narrative where it’s trusting that things will eventually reveal themselves. Hopefully, the reader has an experience that feels organic about the experience of the mind, what I call the music of consciousness.

This is someone writing who finds himself in a new, liberated mind and I wanted to honor that and capture the new sense of freedom that comes with that, so a feeling of flow on its own terms feels like a rewarding encounter.

Q. Your narrator tries writing an epic novel about a fictional toxic incident in West Virginia. His family members aren’t thrilled. Were you worried about how real West Virginians would react?

Growing up there, you’re very aware of how the place is portrayed. The book is trying to engage with the fact that it’s not possible to get it right. To define West Virginia is to miss it entirely. It is a place of constant change and instability.

I’m suggesting that it’s in everyone’s best interest to let go of the simple ideas of the place and see them in relation to context. Often with a place like West Virginia, the singular version — poor and in the middle of nowhere and burned to crap – caused a lot of problems and pain by allowing people to write it off or to justify doing things.

Q. The therapy hallucinations are pretty wild. How much was autobiographical?

There are definitely parts from my own experience. I imagine stuff for a living and I never could have imagined the scale of what this was going to be like. Still, a lot of stuff changed to fit the need of the narrative.

But the giant snake with a skull for a head? I had a run-in with that.

Q. Your narrator obsesses over Michael Herr’s Vietnam classic, “Dispatches.” Did you relate to it in the same way?

I was just using what I was reading. It’s a remarkable book but I wasn’t obsessing like the narrator. I just thought, “Why don’t I use this as material and see what happens?” It immediately opened a clue on how to do stuff. The same with “Out of Sheer Rage” by Geoff Dyer. I would put stuff right into my book and it would cause other things to happen. So often we try to force stuff. If you play with what’s right in front of you it can lead to the most unexpected things.

Related Articles

This week’s bestsellers at Southern California’s independent bookstores

Novelist Benjamin Myers talks crop circles and climate change in ‘The Perfect Golden Circle’

The Book Pages: Maggie Shipstead brought a book to Tahiti. She’s glad she did.

‘Great Circle’ author Maggie Shipstead shares the origins of new short story collection

Explore LA’s iconic ’60s film and art scene in new book about Dennis Hopper and Brooke Hayward

Q. Is that the way you approach life, too?

Psychedelics teach that if you try to run the show you’ll feel quite a lot of suffering. Going with things can yield a remarkable time. That sounds hippy-dippy and woo-woo but it is ultimately true.

The average Will walking around eating a sandwich is not unintelligent but is nothing special, but my imagination can get into really cool stuff and I’m grateful for that. The key is to get your ego out of the way. It’s not that different than a meditation practice. Things will click and reveal themselves to you if you are patient and open to it.