Growing up in Derry, Northern Ireland in the 1980s and 1990s, Kerri ní Dochartaigh was struck by trauma at every turn.

The Troubles – the violent conflict between Protestants and Catholics – lodged terror in ní Dochartaigh’s young soul, especially as a child of a mixed Protestant-Catholic marriage. And amid the fear, bombings, and political strife, she also endured deep, personal losses as family frayed, friends were killed, self-hatred festered, and darkness lodged its gnarly teeth in her.

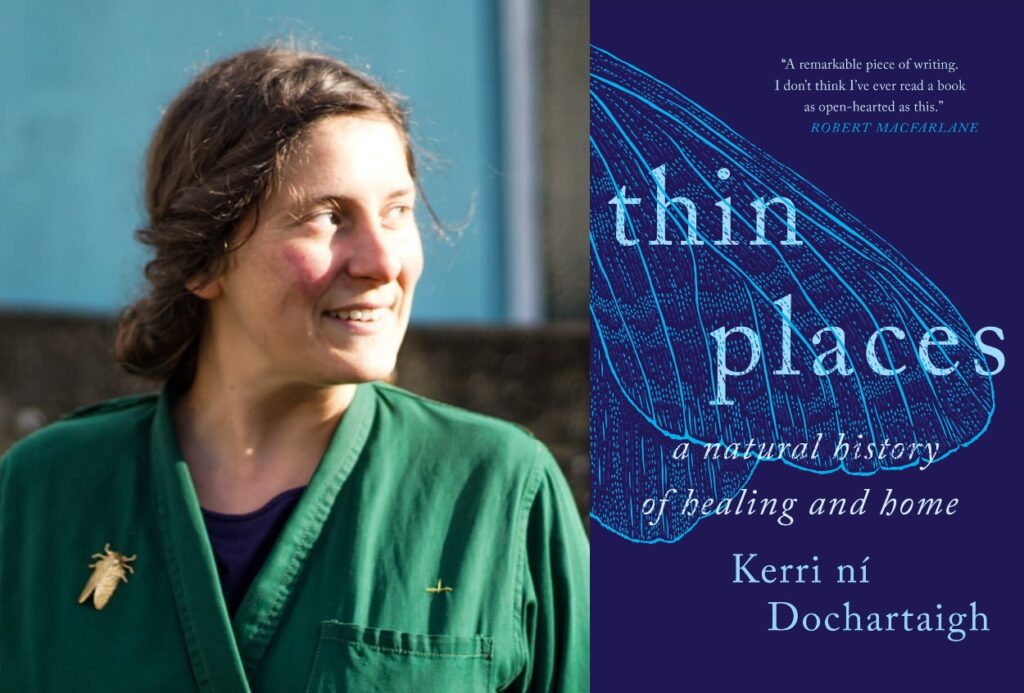

But ní Dochartaigh finally began healing, a journey she describes in her haunting new memoir, “Thin Places, a Natural History of Healing and Home.”

Constantly uprooted, she moved from place to place, often feeling alienated from the human world. Despite the black crow that invaded her dreams, ní Dochartaigh found refuge, and eventually, recovery in the natural world, particularly in thin places, “places that make us feel something larger than ourselves, as though we are held in place between worlds, beyond experience,” she writes.

Celtic tradition is rich in thin places, often sacred or natural sites, where the veil between this world and the other world (whatever that means to you) feels almost transparent. It’s a spiritual experience and often a transformative one.

Thin places “are in many ways a form of stopping place, liminal space that feels like it has been set aside for silence and deep, raw solitude…,” writes ní Dochartaigh. “A place to imagine what it all might mean, how we have been, how we maybe could be – a space to more clearly see a way through.”

Our video interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Q. Why write a memoir?

A memoir is written for the self in the early stages. Then it kind of shapeshifts a bit and turns into something that’s going to be marketable, changing completely. It moves away from being about the self or for the self. It starts to speak to so many other people’s experiences. I’m drawn to memoir because of that.

Q. But “Thin Places” didn’t start out as a memoir.

It started as an illustrated children’s book, about a little girl and a magpie. A number of years later, I took the seed of that and turned it into a short poem, which was just about the River Foyle that runs through Derry. That grew into a series of political essays. I left it for a very long time, and then it became a single essay that was about insects and The Troubles. So it went through this whole life cycle.

When that essay came out in the United Kingdom, the response I got from readers, agents and publishing houses was so vast that I kind of realized that people wanted more. It then became the memoir. I’m really intrigued how that form, and the hold that something has on you, are directly linked. It won’t live in another form again. In writing it as memoir, I was able to let it go and begin all the other things I wanted to write that I couldn’t write until I wrote “Thin Places.”

Q. Shapeshifting and threads are important to your narrative. Can you tell me more?

Shapeshifting is a huge part of Irish folklore. When something bad might happen within a family, all the sons will turn to birds. You’ll have wild geese stories or the children of Lir who become swans. I never felt I really fitted into a lot of the forms or the skins I saw around me. So I’m drawn to the idea that inherently we are all multilayered. The surface of the water has layers beneath it. And the soil has strata. I suppose something about shapeshifting speaks to me in that way.

With the idea of threads, I’m a big believer that we’re all more connected than we’d like to believe. There’s a harpist up there who is playing and we all are part of it, either the string or the reverberations, the echo or the inspiration or whatever. I’m not religious, but I am spiritual. I am drawn to that idea of connectivity and the responsibility that comes with living in relation to each other or the natural world.

Q. Your book has been called nature writing and Troubles memoir. How would you describe your book?

It came highly recommended for a nature writing prize in the UK, but even in the run-up to the event, when I would do book signings, “Thin Places” was never in the nature writing section. So, I find it really hard to define any writing because I come at any piece of writing in the same way. It all just comes from this place of trying to get close to the subject. (Writer) Robert MacFarlane described it to me very early on as writing about wonder. I suppose that may be the closest description I’ve heard.

Q. Are thin places more accessible to people who are in a tough place in their lives?

No, no, definitely not. I mean, I’m in a really good place in my life right now and have been for quite a while, and I still find thin places consistently. I still stumble upon them or I go looking for them. How you experience a thin place has to do with the frame of mind you’re in. It can either really lift me up or drag me a bit deeper. In a way, you bring yourself to a thin place, but you also bring where you’re at, emotionally and psychologically.

Q. Where is the thinnest place you’ve ever been?

At the top of the housing estate where I grew up. I’ve never gone back, intentionally. But there’s a part of me that wonders what it would feel like. Another place was my primary school in the middle of a very Protestant area, close to where we were petrol bombed. There’s this disused kind of concrete labyrinth there that must’ve been part of the play park at one time. I’ve been there as an adult and felt like, “Whoa, this is really very special, a very charged place.” They’ve since knocked it down and built on it. I’m intrigued to go back and see, “Do I still have the feeling? Is it held in the land? Is it the location or is it held in stone?

Q. Your book is both beautiful and introspective, forbidding and extrospective. How difficult was it to juxtapose these vastly dissimilar realities?

We live with the horror of what it means to be alive at this time, as well as the intricate beauty. I hear on the radio what’s happening in Ukraine as I watch my son hold a butterfly for the first time. They’ve literally co-existed. Something that used to really affect me was when everything felt so dark I wouldn’t know how to find joy, or I would feel shame for feeling it. I didn’t know how to make room for light. I suppose that’s what the natural world and these places have taught me. New life starts in the dark. Hope begins in the dark.

Q. How do you think our contemporary disconnect with the natural world is affecting us? And how is it affecting the natural world?

It’s definitely affecting both. We are the natural world and when something is ill-treated, it’s going to affect us. And I suppose we’re also not respecting ourselves by disrespecting what we share the earth with. I talk in the book about how that trauma creates this self-hatred. So the more we do against the people and the animals and the surroundings, the more we do against us. It’s grief to think about what we’re losing. And unless grief is allowed to follow its natural course, it takes root and takes over.

Q. Your book explores the effects of trauma–both historical and contemporary, geopolitical and personal. And even when you found comfort in nature, you were uncertain whether you would heal and be able to rebuild your life? What ultimately helped you on the road to recovery?

I guess when we fall in love, when we know that person can see our higher self, can see our healing, and trust that we can heal. So going into the natural world with someone (her partner) who trusted that I was going to get better and who was going to stand by me as I did it was the first step. I also stopped drinking and started therapy. It’s a lifelong journey that I am going to be on. I’ve had a lot of trauma.