Every generation must face its own fight, says Ukrainian-born Mikhail Gofman, associate professor of computer science.

In his family, struggles run deep.

His grandparents survived on grass and tree bark during the 1932-33 famine under Russian dictator Joseph Stalin, who resorted to starvation to stifle Ukrainian nationalism and force communist, collectivist agriculture upon the breadbasket that was Ukraine.

Gofman’s grandparents (Zenovi and Bronislava Flair) fought in World War II, and others died in the Holocaust.

Now Gofman, who was raised in the city of Artemovsk, which reverted to its original name of Bakhmut in 2016, is facing his own battle.

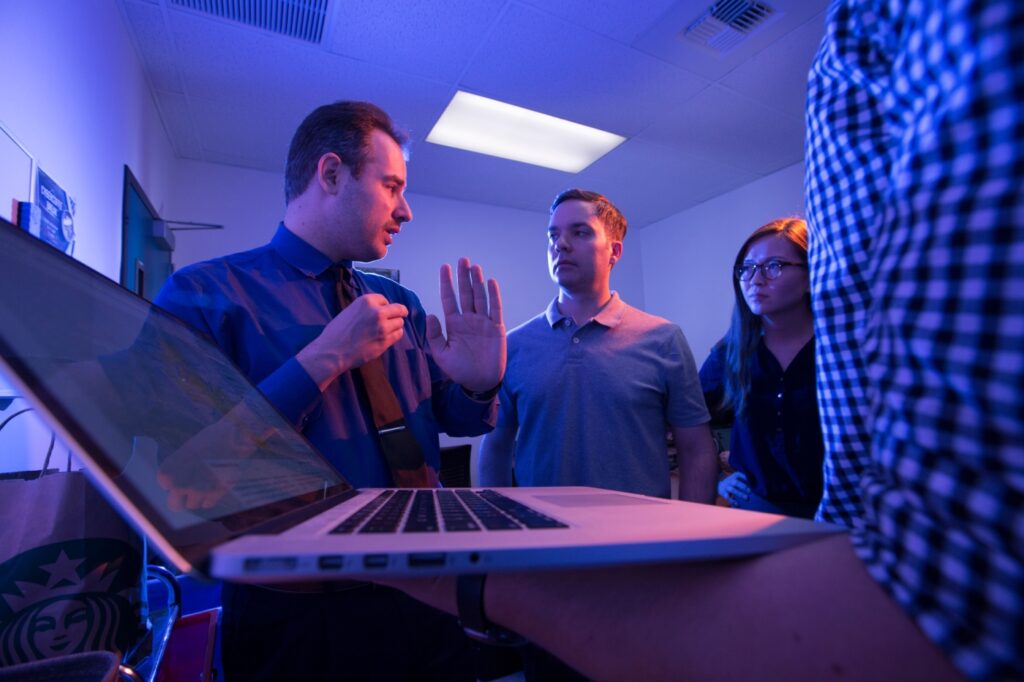

As director of CSUF’s Center for Cybersecurity and a certified information systems security professional, Gofman, a Ukrainian refugee who immigrated with his parents and grandparents to the U.S. in 1995 when he was 10, is keeping a close watch on his native country as the conflict in Eastern Europe continues.

Although his parents, Igor and Yelena, are safe in New York, Gofman worries about his uncle and his relatives who remain in Ukraine, as well as friends who live in bomb shelters.

And he’s monitoring the continued cybersecurity threat to his country, the second-largest in Europe after Russia with a population of 40 million, that since the war began in late February has significantly thinned.

“The kinds of Russian attacks we’re concerned about are Advanced Persistent Threats,” Gofman said. “We’re talking about highly sophisticated, state-sponsored attacks targeting critical infrastructure, military communications, the economy, and other significant targets that, if hit, could give Russia strategic and tactical advantages in the conflict.

“They’re not trying to steal your credit card number or get into your bank account. They want to get military secrets, they want to mess with critical infrastructure, they want to spread mass disinformation to affect the outcomes of elections.“And they’re extremely well-funded,” Gofman added. “These cyberattacks are carried out by professionals.”

Things can change

So far, Russia has not unleashed notable sophisticated cyberattacks against the U.S. during the ongoing Ukraine crisis, or against Ukraine’s infrastructure, Gofman said.

“However, this can change depending on the escalation,” he said.

Gofman said Russia can attempt to cripple banks, shut down the electrical grid, and affect other vital services.

He noted that APTs are incredibly stealthy and that some have previously taken months or years to discover.

“As we speak, it’s possible that the systems have already been infected and the data is being exfiltrated — we’re just not aware of it,” Gofman said.

“Even worse, the malwares can be in a dormant state waiting to be activated when the time is right if and when the conflict escalates,” he said. “At the same time, it’s also true that the U.S. has the full capacity to respond to Russian attacks with just as crippling cyberattacks.”

Gofman said he’s sure that Ukraine and its allies have invested significant time and resources trying to perform penetration tests on the systems controlling Ukrainian critical infrastructure to ensure resilience against the onslaught of Russian attacks.

Ukraine also has recently started recruiting volunteers to its IT army, whose job is to perform both defensive and offensive maneuvers in the war with Russia, he said.

Evolving landscape

CSUF’s Center for Cybersecurity, of which Gofman is the founding director, was created in response to the increasing number and sophistication of cyberattacks affecting millions of individuals, organizations and government institutions every year. The cyberthreat landscape has evolved from hacker enthusiasts breaching systems for enjoyment to highly organized networks distributing malicious software for profit, to large hacktivist groups working to undermine everyday operations of organizations, and to government-funded efforts to wage cyberattacks of remarkable levels of sophistication and destructive power.

Gofman, who earned his doctorate in computer security from State University of New York at Binghamton and whose work has been published in top-tier security conferences and journals, said he feels it’s his moral duty to serve the U.S. and Ukraine with his cybersecurity skills.

And the skills he has and that he’s teaching his students are unique.

“Cybersecurity requires more than academic and technical competence, but mental and emotional resilience,” he said. “Cybersecurity is a militaristic field in some sense. You’re not shooting at people, but you’re basically fighting against another human being, against another intelligent agent.

“You must have scientific skepticism, but that is not enough.

“When you do cybersecurity, you’re dealing with a deceptive agent. You must think like a magician. You need to be creative but also stringently methodical. You need to be Beethoven with the heart of an accountant.”

Gofman said CSUF will be applying for designation as a Center for Academic Excellence in Cyber Defense Education, a national stamp of approval awarded by the Department of Homeland Security.

“I’m glad I have the opportunity to be part of this,” he said. “There is so much potential.”

Related Articles

Project Rebound scholars pay it forward with new program aimed to help juvenile offenders

CSUF honoree says keeping an open mind led to career success

CSUF professor brings thoroughly modern methods to theater education

Supreme Court nominee brings diversity, a new perspective

Cal State Fullerton can’t keep up with Duke in NCAA Tournament loss