In recent years, Chinese art has disappeared from Western museums — looted art being stolen once more. The Chinese government has denied accusations that they are behind the thievery as a GQ article about “The Great Chinese Art Heist” is now being made into a movie by Jon M. Chu.

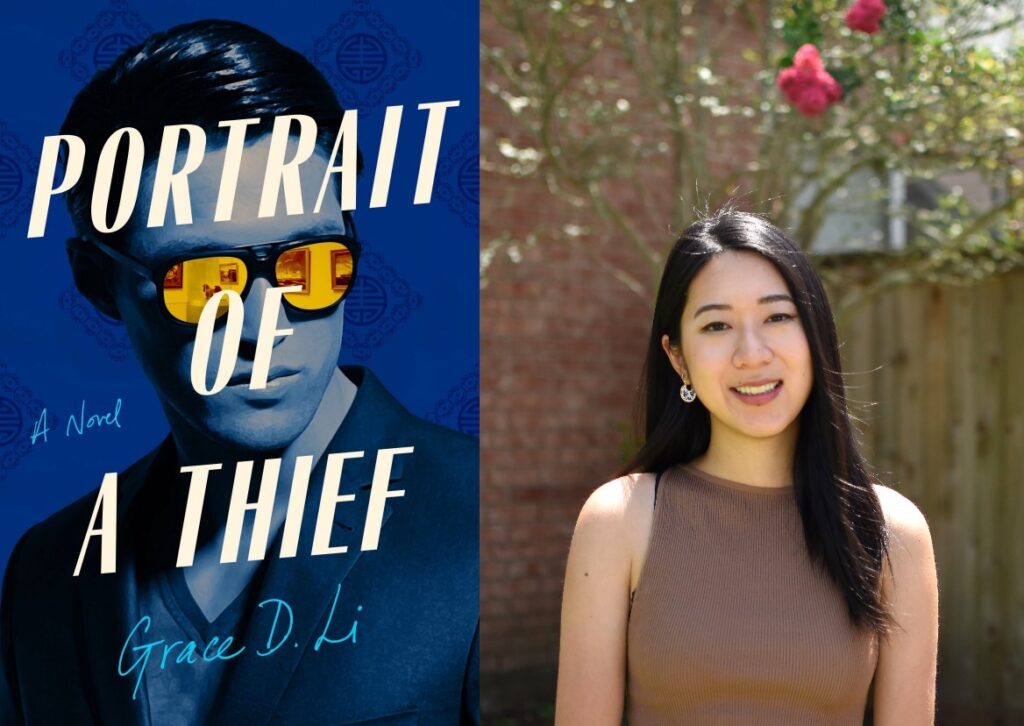

There’s another, totally fictionalized take on the topic: Grace D. Li’s debut novel “Portrait of a Thief,” which imagines five college students, all the children of Asian immigrants or Asian born, being hired to steal five missing Zodiac heads from museums around the world.

Related: Get the free weekly Book Pages newsletter about bestsellers, authors, recommendations and more

Li was inspired by the political issues surrounding looted art, but also the heist movies she loves, like “Ocean’s 11,” and her characters lean into the tropes of those films, especially in the opening chapters as Will Chen gathers together his crew for the job.

But Li, 26, wasn’t planning a career as a crime thriller novelist. In fact, she finished the book while in her first year of medical school at Stanford University. And while her book has already been optioned by Netflix for a series, Li is still immersed in med school.

Li spoke recently by phone about how she juggles two disparate lives as a writer and student and about whether she would help steal the art back if she knew she wouldn’t get caught.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q. Did you want to be a writer or a doctor growing up?

I always loved to read and write. When I was in elementary school, my parents had a meeting with the school librarian because they worried I was reading too much. But I never thought writing was a career path.

In college, I was a biology major and creative writing minor. I wrote my first novel in college while taking organic chemistry and physics — I needed to do something that wasn’t either of those things. I wanted to see if I could do it. I wrote it and put it away and no one will ever see it again.

I thought that I’d always just have a file on my computer with all these unfinished stories, so this has all been very weird.

Then I did Teach for America in New York for two years, teaching high school biology and a creative writing elective.

And I wrote my second novel when I was studying for the MCATs. It was a fantasy novel that was a feminist reimagining of the Iliad from the perspective of Helen of Troy. That book found me a literary agent and we revised together and had a couple of close calls with publishing houses but nothing ever landed.

I was always writing, thinking, ‘I’m writing my little stories in my free time.’

Q. How did this novel come to be?

I really wanted to read a book about this subject and no one had written it. I wrote it for me. I finished writing this book during the pandemic the summer after my first year of medical school and things turned out differently this time.

Q. Why didn’t you think you could be a writer?

I never read books by Asian-American authors — I read The “Joy Luck Club” in high school and that was it. That didn’t change until the end of college. I thought writing books was not something that people like me did.

I remember the first time I read a book and thought, “Oh, this is me.” It was Weike Wang’s “Chemistry,” about a Chinese-American graduate student in chemistry. I didn’t know stories like this were possible in fiction. That changed things completely for me.

Q. You worked with the publisher, Tiny Reparations, which was started by Phoebe Robinson to publish more underrepresented voices. How did that shape your experience?

Tiny Rep is doing life-changing work in a publishing industry that is 80 percent white, where 89 percent of books published are by white authors. Almost my entire publishing team are people of color and they really get what I’m trying to say about identity and diaspora and belonging. It means so much to me. It’s not an experience that would have been possible any time except now. I’m so lucky to be alive and writing in this day and age.

Q. The five protagonists are all Chinese or Chinese American but they live in different parts of America, come from different socio-economic backgrounds and have had very different coming-of-age experiences.

That was always really important to me. There’s this idea that there’s a monolithic Chinese-American or Asian-American identity. If you bring five Chinese Americans together their lives will not be the same — I wanted to talk about how economic class and location can influence the way you grow up and see the world.

I could pull from all the different parts of my life, from growing up in Texas to living in New York and now the Bay Area. I felt the most similarities to Lilly, her struggles about identity being Chinese-American in Texas is something I felt growing up there. It was rewarding giving her that arc to work through.

Q. The book returns again and again to the theme of Western imperialism and the morality of stealing art that was looted. If you could do the heist yourself with the guarantee that you would not be caught, would you do it?

I’ve had stress dreams about these heists, but I might do it.

Related Articles

This week’s bestsellers at Southern California’s independent bookstores

We judged these books by the covers, and here’s what people said.

Murder, blackmail and a missing woman in 1950s Hollywood fuel David Baldacci’s ‘Dream Town’

Molly Shannon writes about comedy and tragedy in memoir ‘Hello, Molly!’

This week’s bestsellers at Southern California’s independent bookstores

I generally believe looted art ought to be returned. If the country of origin wants it back it’s a flimsy argument to say that a Western country is better able to preserve the art or can show it to a better-educated audience. When I read about the Chinese art disappearing from Western museums, even though the people taking it were doing something illegal, on principle I was very much for it. I thought, ‘Go for it.’

Q. Does the fact that you’d be serving the interests of a government that crushes dissidents and runs concentration camps for minorities give you pause?

The Chinese government has many problems but Chinese culture and Chinese history does not exclusively belong to the CCP. All my extended family is in China and I can love them without supporting the government in power. It’s a complicated issue but things can be held separately. The people of China can’t be punished at all times and in all ways for its government.