No NFL team should ever be in salary cap hell while picking in the top five of a draft.

Money is only supposed to run out on contenders who load up for Super Bowl runs, not on a 4-13 team tied for the league’s worst record since 2017 at 22-59.

But that’s where the Giants are, hamstrung in constructing their 2022 roster while other rebuilding teams like the Jaguars and Jets are free to spend away.

“If you’re that tight against the cap, usually you’ve either made a lot of mistakes or you’re among the better teams in the league,” former Philadelphia Eagles president Joe Banner (1995-2012) said in a phone interview this week. “It tells you they made a lot of changes in the front office for reasons that aren’t baseless.”

The Daily News spent the last two weeks asking executives, cap specialists and league sources in and around the Giants to explain the causes and severity of this predicament. The point is to understand how they created this dilemma so they can avoid doing it again.

And here is what happened in 2021, according to those sources:

1) The Giants overestimated their chances of winning and overspent in free agency

2) They kicked money down the road by making exceptions to their contract philosophies

3) They incurred more than double their typical cost of injured player money

4) They didn’t follow through on some options to offset those costs

5) And they restructured nine players to delay cap charges that are hitting them now

The cumulative effect was adding around $15-to-20 million onto this year’s 2022 salary cap that Giants brass hadn’t originally planned for.

Kevin Abrams, now the Giants’ senior VP of football operations and strategy, was ultimately the final signoff on all contracts and finances that went to ownership. The buck stopped with Abrams, then the assistant GM.

GM Dave Gettleman and head coach Joe Judge had visions and voices on what the 2021 team could be and what length of commitment the Giants needed to make to players. Ownership supported all of that.

New GM Joe Schoen is trying to show discipline now, with cuts and pay cuts and frugal spending. The idea is to weather short-term pain in order to yield long-term salary cap health.

“If you take a blind look at the Giants as their new GM,” said Jason Fitzgerald, founder of the leading NFL cap website OvertheCap.com, “you’re just getting through the 2022 season and getting ready to reset the roster in 2023.”

Multiple league sources say the most recent comparison to Schoen’s current strategy is how Houston GM Nick Caserio managed the 2021 Texans: by signing veterans to cost-effective, one-year contracts to simultaneously compete on the field and avoid long-term commitments.

Ten of Schoen’s 12 outside free agent signings since March 11 have been one-year contracts.

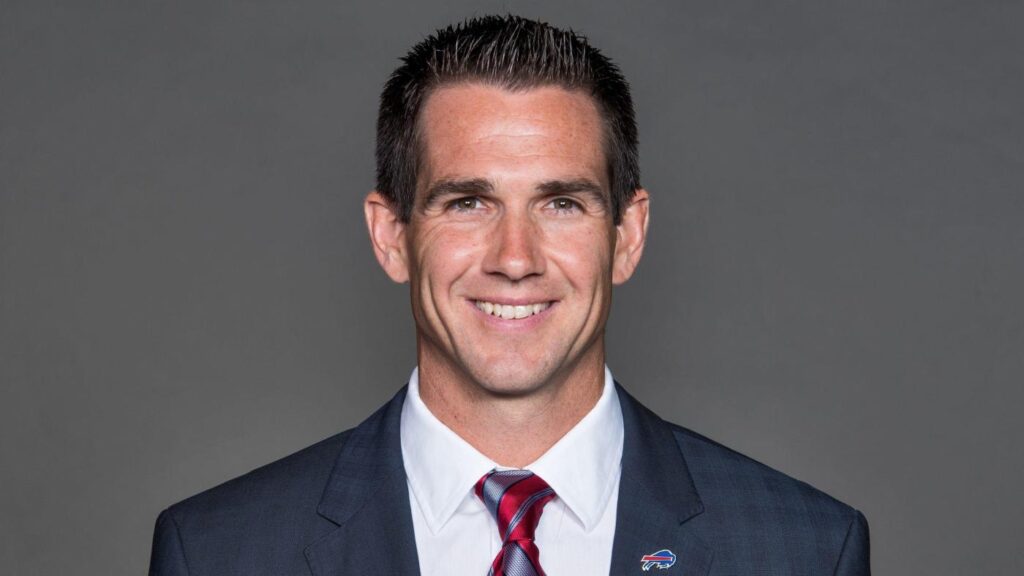

Brandon Beane and Schoen did something similar with the Buffalo Bills in 2017. The Giants’ 2022 season will be difficult, but Schoen is doing it in the interest of 2023 and beyond.

“I don’t think they expected to have their record last year, but there are some long-term solutions,” said former Jets GM Mike Tannenbaum (2006-2012), who now runs the NFL website and football think tank ‘The 33rd Team.’ “In year one, you’re assessing your team and you want to absorb those cap hits.”

“You don’t want to spend a lot of money to only have four wins,” said Banner, who feels the Giants are showing even more financial restraint than Houston did a year ago. “You’re resetting the organization and preserving as much money for the future while still not wanting to embarrass yourself on the field.”

ALL IN TO WIN

The Giants overestimated their momentum coming out of their 6-10 season in 2020. They saw how weak the NFC East was and thought they could win the division in 2021. Fans were coming back into MetLife Stadium, and the Giants wanted to give them a season to remember.

They set spending limits initially, aware of the NFL’s salary cap plummeting $15.7 million to $182.5 million due to pandemic shortfalls. But a targeted plan to retain Leonard Williams and upgrade the offense grew more aggressive as they built momentum built in their recruitments.

In total, they spent $118.5 million in guaranteed money on Williams ($45 million), wide receiver Kenny Golladay ($40 million), cornerback Adoree’ Jackson ($26.5 million) and tight end Kyle Rudolph ($7 million) alone.

“They overcommitted, which started with the Golladay one, which came out of left field,” Fitzgerald said. “Then they followed it with the Adoree’ one, which came even more out of left field.”

Abrams was the final sign-off on all contract offers. He knew the Giants’ big spending would make 2022 difficult but approved the investments. It was a calculated risk. Gettleman had control of the 90-man roster and oversaw the assessment that the team could win.

Judge wanted to sign the players to multi-year contracts. The head coach believed he had at least a three-year runaway to rebuild the team and get it humming on all cylinders. He didn’t want one-and-done rentals. He wanted to build a program with foundational pieces.

Director of football operations Ed Triggs was involved in contract preparations and negotiations. Head athletic trainer Ronnie Barnes, the club’s senior VP of medical services, relayed medical sign-off from the club’s doctors, as Gettleman described while explaining the Rudolph move.

Those investments required a compromise, though, on the Giants’ contract structure philosophy: They had to reduce the players’ first-year salaries and pay them signing bonuses to keep their first-year cap number down and fit them into 2021.

This inflated future salaries and cap numbers by kicking cash down the road and spreading the signing bonus damage throughout the contract. And outside of Golladay’s deal, the club avoided tacking on empty void years, which concentrated a lot of the cash and cap pain on 2022.

The result: Williams’ three-year, $63 million extension (a $21 million average cap hit in a flat contract) ballooned from a $11 million cap hit in 2021 to $26.5 million this year. Jackson’s three-year, $39 million deal ($13 million on average) skyrocketed from $6.1 million in 2021 to $15.5 million this year.

It was the same with Golladay’s four-year, $72 million deal ($4.4 million in year one, $21.1 million in year two) and Rudolph’s two-year, $12 million contract ($4.75 million in year one, $7.25 million in year two).

The Giants anticipated some of that added cost, because it was never going to be realistic with the NFL salary cap plummeting to keep all contracts flat while building last year’s team.

With those four signings alone, though, the Giants added a total of $70.4 million to their 2022 salary cap, including $12.4 million of extra cap space due to the contracts’ structures.

That was on top of some heavy in-season 2020 investments: a three-year extension for Graham Gano with the second-most guaranteed money ($9.5 million) at signing of any kicker in the NFL; and a three-year extension with $20 million guaranteed for the since-released Logan Ryan.

Finally, while any NFL team can offset costs in a given season by offloading player contracts through trades or releases, the Giants opted to stay the course and found no relief elsewhere.

HURTS SO BAD

The Giants exceeded their estimates on paying injured players at historic levels, too.

They had the sixth-most cap money of all NFL teams sitting on injured reserve for 2021, according to Over The Cap, with 23 players incurring $40 million in charges.

A lot of that is planned for. Many of last year’s players were key, rehabbing contributors who would have been paid on the active roster anyway, for example, such as Daniel Jones ($7.1 million of I.R. cost) and Sterling Shepard ($5 million).

But sources said while the Giants typically see a $3.5-4.5 million of injury impact above expectation per season on their salary cap, their 2021 injured reserve bill went well over $10 million above expectation.

That is basically a measure of what it cost the Giants to replace players with injuries, above anticipated costs, taking into account who was likely to make the team and who wasn’t. And last year’s number was among the highest ever recorded for a team using that internal metric.

Fitzgerald the Giants’ decision to carry so many players on I.R. rather than reaching settlements contributed to the problem.

“Most teams usually come to an agreement with injury settlements,” Fitzgerald said. “The Giants didn’t do that.”

The Giants had several reasons for carrying different players, sources say. For some, there was no financial upside to settling a player who was guaranteed to be out for the rest of the season. The team would have had to pay the full tab on that contract just to get the player off the roster.

In other cases, agents might not have wanted to settle for 90 cents on the dollar if they feared a risk of a setback in rehab past Week 18. And some of the players were guys the Giants were hoping could come back or didn’t want to risk losing to free agency once they settled.

So why was the Giants’ large injured reserve bill a problem? Because it pressed them so close to the 2021 salary cap spending limit that it forced them to do something almost unheard of:

Restructure several contracts late in the season just to stay within the NFL’s rules.

“That’s not something you ever see,” Fitzgerald said.

DELAYING THE PAIN

The Giants restructured nine total contracts to clear cap space, which added $12.7 million to their 2022 books, per Over The Cap. The three that stuck out were the late-season restructures on injured center Nick Gates, punter Riley Dixon and Rudolph.

Gates was out indefinitely with a career-threatening injury, and Dixon and Rudolph since have been released. But the Giants had to convert money in their salaries to signing bonuses just to stay cap compliant late in the year.

Those three restructures only kicked $733,056 of cap damage into 2022. They were an obvious sign of the Giants’ win-now gamble backfiring, however, before the season had even ended.

Fitzgerald said the other six restructures were typical of how teams operate nowadays but called the last three “bizarre.” He said “the only team I ever remember doing that was the Rams” early in Les Snead’s GM tenure, when St. Louis did it intentionally.

Indeed, according to sources, the Rams of that 2013-14 timeframe consciously decided to absorb the cash and cap pain of their contracts simultaneously, rather than pushing it into future years.

Philosophically, like the Giants, the Rams always have tried to match their cash spent with their cap absorbed. Schoen is trying to get the Giants back there now.

It’s hard to ignore the cause and effect of these financial decisions, though:

The Giants’ two largest restructures last year added $4 million onto corner James Bradberry’s 2022 cap and $3.5 million onto Blake Martinez’s. Now this spring, Martinez had to take a pay cut and Bradberry is due to be traded.

Here’s the good news: Schoen’s Giants no longer think they are something they aren’t.

“The new guys are doing the right thing by taking this first year to clean it up and get it in the right position as opposed to fooling themselves,” Banner said. “It’s a hopeful sign to the fans that the new group is not doing that. They’re doing it the way that teams who have had successful turnarounds have done it, where they turn it around in year two.”

Banner cited his Eagles, the 2017 Bills (when Schoen started), the Titans turnaround of the last seven years, and Kyle Shanahan’s 2017 49ers to some extent as clubs who took a smart and long-term view of their team cleanups.

“The Saints believe they’re a good football team so they’re pushing every lever possible to create cap room,” Fitzgerald said. “The Giants probably could have done something like that this year, too, but there’s no benefit because they would be locking themselves into another year.”

()