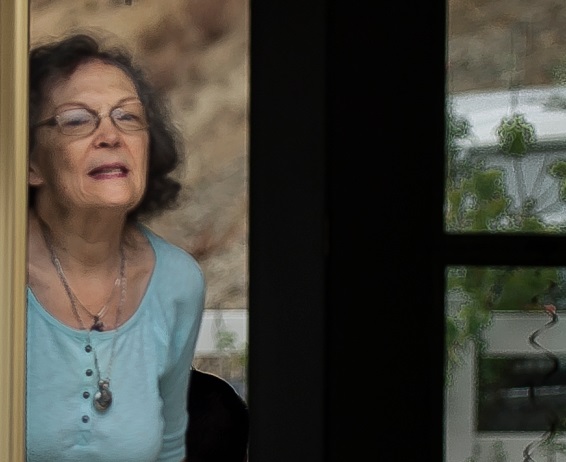

Diane Ramirez and Jeff Miller at the Spectacular Prom in 2018. (Courtesy Jeff Miller)

First, the judge asked people to leave the courtroom — and stay outside — if they might be upset by his ruling.

That’s when Diane Ramirez’s parents knew what was coming.

After a 20 minute break, Riverside Superior Court Judge Timothy F. Freer threw out the murder charge against Michelle Morris-Kerin, the foster parent who refused to call 911 for some seven hours while Ramirez moaned in agony and coughed up blood, her vital signs fluctuating, her skin cold to the touch.

Ramirez, 17, died the morning of April 6, 2019, after a twisted intestine cut off blood to her bowels. The condition, “small bowel volvulus,” might have been corrected had she gone to the hospital at the first signs of distress, prosecutors argued.

Freer emphasized that he felt deeply for Ramirez and her family, and wasn’t concluding that Morris-Kerin displayed no criminal conduct. Rather, he found that the Riverside District Attorney failed to present convincing evidence that Morris-Kerin’s inaction substantially contributed to Ramirez’s death.

“The evidence established by experts was, in general, volvulus can be treated by surgery, and the sooner the better,” the judge said. “There was no evidence that the volvulus that afflicted Diane was one that could be treated, or one that would have been fatal no matter what.”

Michelle Morris Kerin (Courtesy of Riverside County DA)

The condition can kill in hours, or it can take days, the judge said. If Ramirez’s was the fast-moving kind, it might have been too late no matter what Morris-Kerin did. If Ramirez’s was the slow-moving kind, it might have already been too late, the judge said.

“That the defendant caused her death is not a reasonable inference from the testimony,” Freer said. “Speculation is required to conclude intervention would have helped.”

The expert doctors who testified to the grand jury did not treat Ramirez in the emergency room, so they wouldn’t comment on whether she could have been saved. The emergency room doctors who actually treated Ramirez refused to testify without a subpoena, and were never called.

The ruling was a blow to the D.A.’s office, but many counts against Morris remain, including involuntary manslaughter, willful cruelty to both children and adults, and lewd or lascivious conduct with dependent adults. The D.A. may appeal the judge’s decision, but that would stall movement on the other charges.

“We will be reviewing all available appellate remedies but cannot comment further due to pending litigation,” said spokesman John Hall by email.

The order was filed under seal because it included details from grand jury testimony, which remains under seal.

Morris-Kerin’s attorneys, from the Public Defender’s office, asked Freer to reconsider the ankle bracelet she must wear. The judge declined to do that just yet. The public defender may ask Freer to dismiss other charges against Morris-Kerin as well; in the meantime, a trial readiness conference is slated for June.

Angel Cadena Ramirez, mother of the late Diane Ramirez, protests with others for justice for her daughter.

Painful details

The judge read his entire 30-plus-page ruling into the record, including painful details about Ramirez’s last few days that were hard to hear.

Ramirez had cerebral palsy, seizure disorder and other challenges, as well as an indomitable spirit and mischievous sense of humor that people found infectious. She’d place fake spiders in her locker to scare the teachers who helped her open it. She was in 11th grade, assessed at grade level at Murrieta Mesa High School, where her “prom-posal” to quarterback Jeff Miller made the TV news.

From her birth until 2018, Diane lived with both her parents and siblings. Then the Ramirezes separated and a difficult divorce ensued. Diane spent the majority of time with her mother, visiting often with her father, until her mother’s personal issues made caring for Diane difficult. Her father was not yet in a situation where he could take over, so the county temporarily placed Diane in the Morris-Kerin home while the parents worked toward reunification.

Controversy has dogged Morris-Kerin for years. She began her foster career in Orange County in the mid-1990s, caring for profoundly disabled children. She quickly clashed with officials who asserted that she suffered from Munchausen by proxy, a behavior disorder in which caretakers exaggerate children’s health problems and subject them to unnecessary or inappropriate medical treatment, according to records. She sued, won a settlement, then moved her business to Riverside County to escape what she called “persecution.”

Diane Ramirez “Prom-posal” to Jeff Miller in 2018. (Courtesy Jeff Miller)

Complaints continued there as well. Morris-Kerin “does not take good care of Diane or the children she takes and ‘is just doing it for the money,’ ” one of Ramirez’s teachers told county workers, according to social workers’ internal logs. The state pays about $5,000 per month per disabled child for foster care.

Ramirez wanted to leave. There was a meeting on April 5, just hours before Ramirez fell ill, where Morris-Kerin was told that Child Protective Services was going to place Ramirez elsewhere, prosecutor Jason Stone said. That meeting was critical to Morris-Kerin’s mental state, he argued. Ramirez had been rushed to the emergency room just days before, on April 2, vomiting up blood. The child was stabilized and Morris-Kerin was instructed to get her back to the emergency room immediately if she started coughing up blood again.

But after learning Ramirez would be moved, Morris-Kerin’s attitude was “she’s not going to be our worry,” Stone said. And so, despite the specific instruction, Morris-Kerin repeatedly told her employees not to call 911 even though Ramirez was again coughing up what appeared to be blood. When it appeared Ramirez had no pulse, the workers called 911 anyway — but it was too late.

“The substantial factor is the absolute abrogation of duty to get care for her,” Stone said.

Diane Ramírez and Jeff Miller in class. (Courtesy Jeff Miller)

The judge laid out in great detail why he disagreed, and how the details of Ramirez’s suffering may have inflamed the grand jury’s passions and led to the second-degree murder count despite a lack of evidence.

Ramirez’s mother, Angel Cadena, was deeply disappointed by the ruling. No one would allow a child in agony, moaning and throwing up blood, to suffer and fail to call 911 for 8 hours, she said, by text, “just like no one would stand by a pool watching a child drown. Michelle knew exactly what she was doing refusing to seek medical attention … my Princess Diane already alerted me that she was afraid of her.”

Ramirez’s father, Albert Ramirez, didn’t stay in the courtroom to hear the details. He left after the break. “I’m very disappointed,” he said by text. “I truly believe Michelle murdered my daughter.”