Baseball is always shattering records.

One, though, can never be broken. Jackie Robinson will forever be the first Black man to play in Major League Baseball.

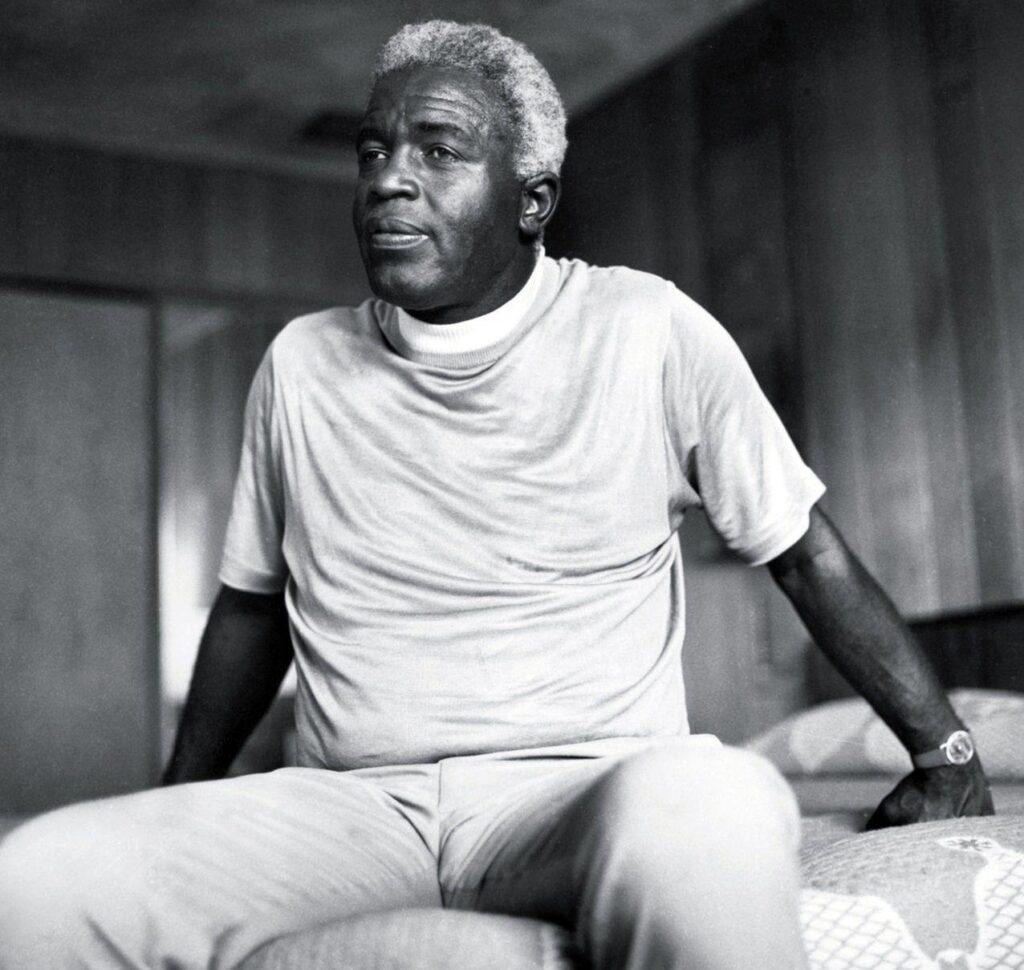

Robinson’s astounding prowess on the diamond was matched by his ability to keep his cool despite the hideous racism he faced. “True: The Four Seasons of Jackie Robinson,” by Kostya Kennedy, chronicles Robinson’s life on and off the field.

This publishes Tuesday, just before Friday’s 75th anniversary of Robinson starting for the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947. So much has been written about Robinson and those heady yet fraught days when he broke the entrenched racial barrier that a new angle was needed.

It concentrates on four years for Robinson: 1946, playing in the minors for the Montreal Royals; 1949, winning MVP for the Brooklyn Dodgers; 1956, his final season and 1972, when he died at 53.

The deeply researched volume stresses what baseball fans noticed instantly — his stance. How he held the bat and his pigeon-toed gait would be copied by kids playing in streets and on fields around the country.

The book is a testament to how he conducted himself — when few people would have the self-control he mustered — and puts Robinson’s life into context.

“In those crucial years in the middle of the twentieth century, America — relieved, proud, post-traumatized — was moving headlong past World War II and at the same time trying to lurch forward, out of the grips of its worst and grimmest sin, to find a way to bend the arc of its own moral history toward justice,” Kennedy writes. “The experience of the war was material both to appetite for change and the resistance to it.”

The modern civil rights movement had yet to begin. When Robinson took the field, Martin Luther King Jr., was only 18. Sure, baseball was America’s pastime, but it could get pretty ugly, depending on who was playing and who was in the ballpark.

Before players had all kinds of protective gear, Robinson’s cap had “a lining of thick cloth and fiberglass, a minimal defense against the pitches that came toward his head, thrown with intent.”

Throughout the book, as Kennedy details some memorable games, he recounts pitchers who took aim at Robinson, other players who used their cleats to draw blood and how he was denied basic services when the team traveled. Robinson could not stay in some hotels with the team, could not eat in the same restaurants.

Before Branch Rickey brought him to the Brooklyn Dodgers, Robinson spent a year with the Montreal Royals. Before that, Robinson became UCLA’s first athlete to letter in four sports — baseball, basketball, football and track.

As a UCLA senior, in the fall of 1940, he met Rachel, a freshman. They were together until his death in 1972, and truly a team onto themselves, which the book explains.

Over the decades, Rachel was his partner in every aspect, working with him for civil rights, raising money for causes and rearing their children. They endured so much together and publicly, no matter how angry or scared, they presented themselves as utterly composed.

As dignified as they were, and as important to bringing about change, what the world saw first was Robinson on the field. In motion, he was magic.

“Of all the attributes that attended Jackie Robinson’s play on the baseball diamond — and there were many — none stood out so magnificently, at the time or in memory, in legend and in fact, as the way that he ran the bases. Nothing else he did as a ballplayer quite so profoundly impacted both the games that he played and, it must be said, the lives of those who saw him play. Robinson could change a game with a feint.”

Kennedy goes into detail about the kids who grew up going to Ebbets Field, and who decades after seeing Robinson play still talked about him reverentially. ACLU boss Ira Glasser was one of those Brooklyn kids. Kennedy’s research has him explaining the old neighborhoods, when you could buy whitefish in one store, comics at another and get a 15-cent haircut.

The tangents remind us of the times. Even those who don’t understand the allure of baseball, need to know the importance of this man.

In his rookie year in 1947, Robinson led the National League in stolen bases. By ‘49, he did so for all of baseball. He regularly stole second, third and even home.

“No one in the league got thrown out more than Robinson did,” Kennedy writes. “‘Don’t worry if you get caught,’ Branch Rickey said. And Jackie did not worry. High volume was part of the strategy.”

He played in games where kids climbed to rooftops that overlooked ballparks, where people crowded outside, as he continued to steal bases and hit consistently. Rickey called him “the best since Ty Cobb.”

Fans, of course, knew. Dodgers pitcher Carl Erskine recalls a kid handing him six items to sign. Why? The kid planned to trade Erskine’s six for one Jackie Robinson autograph.

Off the field, Robinson continued to say what was on his mind. On July 18, 1949, he testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee about Paul Robeson. While opposed to Robeson’s leftist views, Robinson explained that as a baseball player he didn’t like becoming embroiled in politics.

“You can put me down as an expert on being a colored American, with thirty years of experience at it,” Robinson stated. “And just like any other colored person with sense enough to look around him and understand what he sees, I know that life in these United States can be mighty tough for people who are a little different from the majority — in their skin color or the way they worship their God or the way they spell their name.”

As he later wrote to President Eisenhower: “We want to enjoy now the rights we feel we are entitled to as Americans.”

Robinson’s final hit of his Dodgers’ career came in Game Six of the 1956 World Series against the Yankees. The next day, the Yankees won the series. When he returned to Ebbets Field, Robinson cleared out his gear. Although traded to the New York Giants, it didn’t much matter. Robinson had decided to leave on his terms. He took a post as vice president overseeing personnel at Chock Full o’ Nuts.

When Robinson left baseball, he continued on the national stage as a beacon of leadership and spoke forcefully, quietly and effectively about racism. After teammate and friend Gil Hodges’ 1972 death, Robinson had been openly critical of how MLB, even 15 years after his final game, had no Black managers.

He attended the Old-Timers Day in 1972 in Los Angeles, where the respect for him was palpable. Robinson quietly, forcefully pushed for what is right.

As the Rev. Jesse Jackson said eulogizing Robinson, “He didn’t integrate baseball for himself. He infiltrated baseball for all of us, seeking and looking for more oxygen for Black survival, and looking for new possibility.”

And the great No. 42 continues to remind us. Visitors to his gravesite at Brooklyn’s Cypress Hills Cemetery can see his epitaph: “A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives.”

()