Obiajulu Ejiofor did not have an easy life. As a teen, she had barely survived the Nigerian Civil War; then after emigrating to London, she felt isolated and was stung consistently by racism. But she was fulfilled and happy. She was a mother of three, with a fourth on the way; she and her husband, Arinze, owned a pharmacy and he was also a doctor and aspiring musician, the lifeblood of every room he was in. Theirs was a love story for the ages.

Then, suddenly, Arinze was gone, killed instantly in a traffic accident in Nigeria, one that nearly killed their second child, Chiwetel. Depressed and despairing, Ejiofor retreated at first, before realizing it was up to her to make sure her children’s lives weren’t totally derailed by this tragedy.

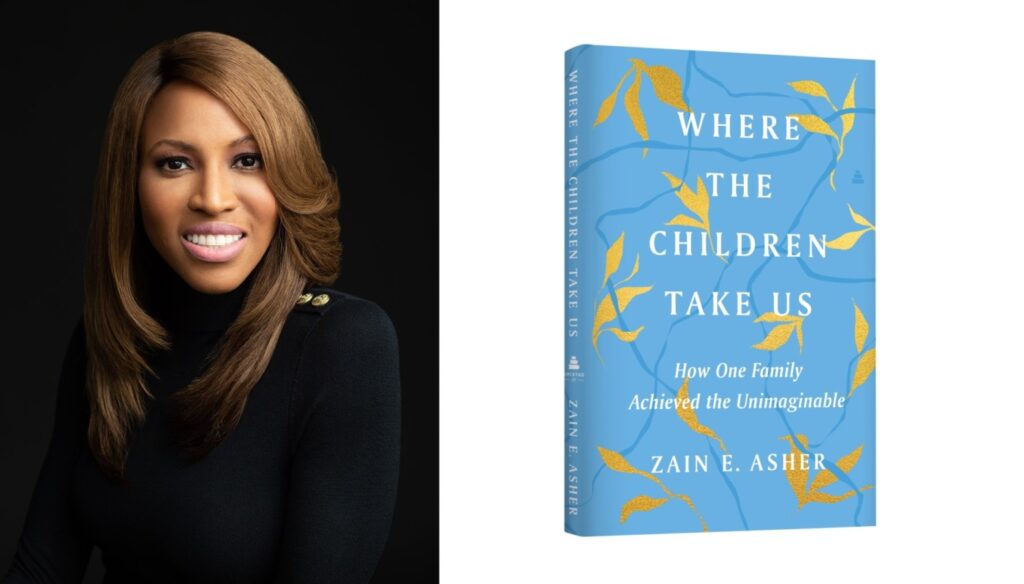

In “Where the Children Take Us,” Zain E. Asher, who was just five when her father died, recounts her mother’s journey and how she shaped her children — the eldest, Obinze, is now an entrepreneur, Chiwetel is an Oscar and Emmy nominated actor, Asher anchors CNN’s “One World,” and the youngest, Kandibe is a doctor. To get them there, Asher’s mother surrounded them with images of Black success and would drive her daughter to Oxford regularly so she could envision herself there; she also cut the wires on the family TV and replaced the home phone with a payphone to prevent the teenaged Asher from being distracted from her studies.

Related: Get more stories about books and authors in our free Book Pages newsletter

Asher spoke recently by video about getting her mother to relive her worst trauma and about what it’s like to always feel like an outsider. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q. What made you decide to write a memoir centered on your mother instead of you?

I hadn’t really thought about writing a memoir until I turned 36, the age my mother was when my father passed away. It really haunted me because I realized just how young she was then. I had my first kid at that time and while I’d always appreciated my mother – even as a teenager I knew she was a remarkable human being – it was when I became a mother myself that I realized what she had gone through. So I wanted to celebrate all that she did.

Q. Your mom was willing to relive all of this and put her whole story out there?

When I first told my mother I wanted to write a book about her, she said, “Why? I’ve done nothing special.”

But when she read it, she was moved. Her life then was all about survival, emotional and physical, so she never had a chance to step back and think about the meaning of her experiences and also how it might affect people reading it.

The first chapter was very difficult to write because my mother had buried a lot of the trauma she went through at that time – she was from Nigeria and an immigrant so she didn’t go to grief counseling or anything. When I interviewed her, it brought up a lot of the trauma and my mother had to set time limits on our conversations because it was too painful. For that chapter, I only got to interview her ten minutes at a time. And we’d have to take a break till the next day or a few days later.

Q. What about your siblings?

They all participated and read the book but it brought up extremely painful memories for Chiwetel and difficult emotions for Obinze who began to rebel then — he was angry and frustrated and my dad wasn’t around and my mom wasn’t interacting. He’s a completely different person now so it was difficult to talk about that period.

My sister, Kandibe, didn’t know my dad at all. In 2019, for my research, a cousin sent a video of my dad speaking at a christening and my sister said it was the first time she’d ever heard his voice. His death had been so painful that nobody really talked about him with her. So it was strangely healing in a way.

Q. What impact did writing the book have on you?

I was quite traumatized by him dying – until very recently I couldn’t really bring up my father without crying. But I didn’t really know my father. I feel as if I’ve been trying to find my dad my whole life and through this book I finally found him. Writing it, I realized just how special a person my dad was – my mom’s brother told me, he entirely modeled himself on my dad. So I did a lot more crying while writing the book but now I can talk about him without crying because there’s closure. I feel like I know him now.

Q. When you were a child your mother sent you back to Nigeria for two years for what Nigerians call “training.” Going from London to an African village was a shock to the system but it definitely influenced your childhood. Do you still feel the impact?

Yes. When you’ve been trained there, it’s so much easier to thrive here. I’ve built up a level of resilience. I get five times as many things done here and I appreciate the time. When you are collecting drinking water, it takes several hours a day. Last time I came back from Nigeria, I thought, “Wow, everything works here.” I come home and can’t believe how productive I am.

I think it’s true of a lot of immigrants – their training ground is much fiercer. I think it’s too easy here.

Related Articles

The Book Pages: Don Winslow’s favorite crime novel, plus we go undercover

Buster Keaton’s life, from silent film stardom to ‘How to Stuff Wild Bikini’ gets a fresh look

Murder, revenge, power: Don Winslow reveals classical inspirations for crime novel ‘City On Fire’

This California medical student planned art heists for her debut novel ‘Portrait of a Thief’

This week’s bestsellers at Southern California’s independent bookstores

Q. Yet things weren’t so easy when you returned to England and experienced racism amongst your peers.

The most difficult thing for me was being falsely accused of stealing at boarding school. Until then, I didn’t know what racism really was, that people thought “Black people take things.” I had just come back from Nigeria where everybody looked like me. I was so excited to be back in the UK. It was devastating. I’ve had to go to therapy for that and it will stay with me for the rest of my life.

Q. You and your mother both had to assimilate in England. How different were your experiences?

It was harder and easier for my mom. In Nigeria, she grew up belonging, fitting in perfectly – she was in the cool crowd in school. But to go from that to England, when she was almost 20, where people wouldn’t even talk to her – that was really challenging. However, whenever she goes back to Nigeria she still belongs and feels at home. So she has both ends of the spectrum.

Q. And you felt like an outsider everywhere

Growing up in England and going back to Nigeria prepared me to be an outsider. In the U.K., I was one of the few Black children in my classes but in Nigeria I was British and they made fun of me for being foreign.

I used to not like it but now I champion being different – it offers you so much, including a different perspective. I was drawn to journalism because I liked the idea of connecting with people from all over. As an international correspondent, you have to be able to connect with people who are very different from you.