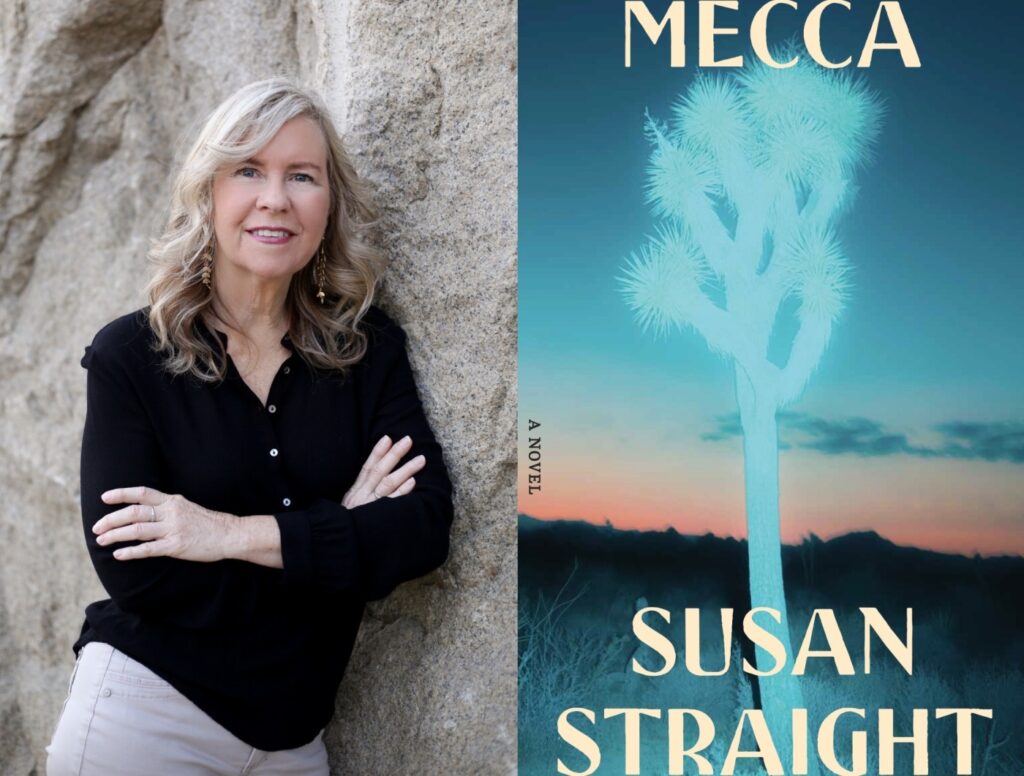

When Susan Straight and I agreed to meet for this interview she sent an email asking, “What about the Cabazon Dinosaurs?” The iconic roadside attraction was the perfect halfway point between us. It was also about a mile away from the San Gorgonio Pass, with its eponymous wind farm that boasts more than 3500 electricity-producing turbines. It’s one of the windiest places in the entire world.

“I think that’s a high wind area,” I responded. I found the exchange amusing not only because “wind” – along with “drought,” “fire,” and “earthquake,” – is basic in our Southern California lexicon, but also the opening sentences of “Mecca” are a gorgeous meditation on it:

The wind started up at three a.m., the same way it had for hundreds of years, the same way I used to hear the blowing so hard around our little house in the canyon that the loose windowsills sounded like harmonicas. The old metal weather stripping played like the gods pressed their mouths around the screens in the living room, where I slept when I was growing up.

Related: Sign up for our free newsletter about books, authors, reading and more

This is the voice of Johnny Frías, who is as close as we get to a classic main character or protagonist in the book, which is in stores on March 15. He is a Chicano California Highway Patrol officer, whose American citizenship is generations deep on both sides. Nevertheless, Frías is often regarded as a foreigner, even accused of being undocumented – more often than his mates, perhaps, because he is moreno, darker-skinned.

I always wanted to speak perfect American,” Frías shares with the reader. “Every time I stopped a driver, I wanted to say exactly the right sentences and mix in exactly the right weird words for whatever I could see about the person, so they wouldn’t get to say, “Officer Frías? What the hell. You’re pulling me over? You sure you’re a citizen?”

Frías’s mother, who died during his childhood after battling multiple bouts of pneumonia, had no qualms about telling anyone who even suggested she was illegal or shouted at her to go back to Mexico, “Mi gente estaba aquí antes de tu gente.” My people were here before your people.

Johnny Frías, who has been on the job for two decades, made a tragic mistake early in his tenure as a CHP. In the course of the novel, however, he will come face-to-face with an individual who witnessed the event and will have to reckon with what he did all those years ago.

Straight’s writing is stunning, absolutely breathtaking. She can move you to tears, and then return you to laughter all in the same paragraph. The novel is made up of interconnected short stories, each told from various points of view. A fair amount of these stories take place during the time of COVID-19. The people we encounter in these stories are not the ones commonly held up as representative of Southern California. There are no agents or ingenues; no screenwriters moonlighting as servers or valet attendants.

There are meth heads who go around stealing metal and copper wire from people’s property. There are Oaxacans who speak Mixtec, and Louisianans whose forebears worked on a plantation. There are the individuals Frías encounters on the job, drivers he lights up and tickets for speeding, having broken taillights, or illegally using the carpool lane. There is Johnny Frías’s father, and also the Vargas brothers, Sergio and Ramón, who help him tend the ranch. There are Frías friends, the men who are like brothers – Manny Delgado, Bobby Carter, Grief Embers – and the women to whom they are married.

Grief Embers, Straight explained, was the name of a real person in California’s history. He was a Black man enslaved by William Crosby, a Mormon Bishop, and brought to San Bernardino in the mid-1800s. He later became the earliest recorded Black owner of real estate in the Inland Empire.

Other characters are: Ivy, who was ten when her mother walked out on her and her father; Ximena, a housekeeper at a Demi Spa where wealthy women go to have plastic surgery and recuperate privately, who discovers an abandoned baby in a guest room; Reynaldo, who leaves his wife and young sons, starts dating a White lady, reinvents himself as a Brazilian and opens a capoeira studio in Venice Beach; and, Merry, a neonatal nurse, who suffers the worst imaginable loss a mother can experience.

It’s not a coincidence that the character, Merry, is named after Merry Clayton, the gospel and soul singer who sang the duet with Mick Jagger on “Gimme Shelter,” and lent her vocals to numerous leading acts as a background singer yet never had her own solo career.

“I listened, over and over again, to ‘Gimme Shelter’ by the Rolling Stones, while I was writing that part,” Straight said. “Merry Clayton recorded that song and then she lost her baby the next day.”

Everyone in the novel, it seems, belongs to a tight-knit community, of family and lifelong friends. “Southern California is this huge, sprawling space,” says Straight, “but for my characters, there are all of these connections that come through geography and family.”

That is both a blessing and a potential burden to this book. While it’s wonderful to move away from the small nuclear family, which has become standard in Western literature, it can be difficult to keep track of so many names, traits, personal histories, and physical movements.

In one scene, while a new couple is exchanging information about their background, it’s plainly evident how truly extended each character’s network actually is. Matelasse, who has roots in Louisiana, tells James that she also has family living on reservation land in Mecca. Then, telling her that he has 75 cousins, he wonders if they’re related.

Reading “Mecca” is like being given a guided tour through Southern California, traveling the freeways – the 10, 91, 55; fearing the rapid spread of fire in the canyons after a small spark catches on a dry, windy day; feeling the extreme heat of Palm Springs and other Coachella Valley towns; driving by orange and lemon groves, Brazilian pepper trees, creosote bushes, sage and brittlebush.

“I think this is my love letter to all the different geographies and places here that are also interconnected,” Straight said. “And the freeways are a huge deal, that’s why I always have where they are going, like if they’re on the 91 or if they’re on the 10 which, by the way, is the Christopher Columbus Intercontinental Highway.”

Related links

How Riverside author Susan Straight embraced family history for latest book

Claire Vaye Watkins explores ‘Darkness’ in novel about family, the desert and Charles Manson

How Joan Didion influenced writers of all identities

How former Gawker writer Ken Layne became Joshua Tree’s Desert Oracle

Sign up for our free newsletter about books, authors, reading and more

Despite having spent four decades in Southern California, I’d never been so intimately exposed to such a wide belt of its land, in print or in person. There were moments when I wished an illustrated map had been included.

I asked Straight what compelled her, a White woman born and raised in Riverside, to write these stories, not simply of Latinx, Black and Indigenous people, but as them, employing the first person in many cases. She explained that she grew up in a multiracial area and that most of her characters are based on people she has met or known, people whose stories she grew up hearing.

“I mean, how lucky am I?” she smiled. “As a writer, a storyteller, I matter not. It’s the characters that matter.”