Andre Henry begins his new book with a blunt warning:

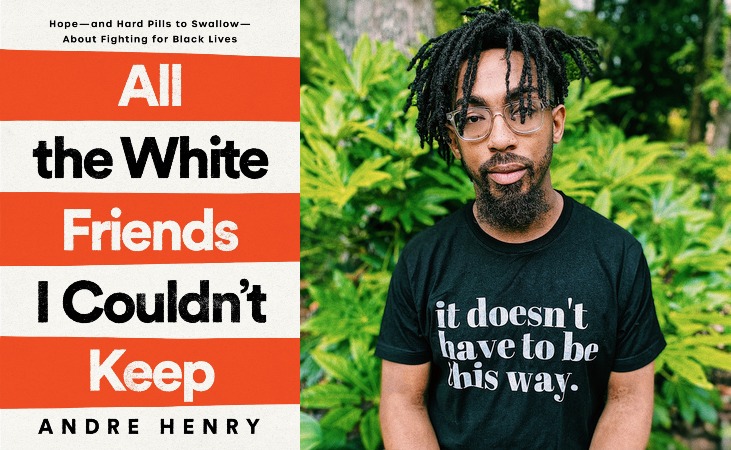

“I need to alert you to something about the book in your hands: this won’t be an easy read,” writes the 37-year-old Inglewood resident and activist in his first book “All The White Friends I Couldn’t Keep: Hope – and Hard Pills to Swallow – About Fighting for Black Lives,” which was published March 22.

Henry, who is also a musician and a columnist for Religion News Service, takes a brutally honest look at the journey that led him to fight against racism that was sparked by the Black Lives Matter movement.

He writes about why he had to lose some White friends; why he doesn’t debate with racists; why he has a right to be angry; and why Black people should not worry about finding a place in White institutions.

“I’m calling out things about how White people behave that are really uncomfortable for some people to look at. People are going to read it and see me criticizing things that they do and they’ve done,” he said during a recent phone interview a few days before the March 22 release of his 267-page book debut.

Inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement, Henry writes about his own path to non-violent activism while sharing the stories of others who have experienced racism.

“I wrote this book for people who are like me before I went through my political awakening. I knew racism was a problem but I thought that racism was a type of individual emotional problem. Like you have irrational emotional hate towards people of a different skin color. But I came to learn that racism is about power and about the way power is unequally distributed along the color line,” Henry said.

One of the things Henry write about that he knows will make people uncomfortable is how he is willing to drop White friends who he says are gaslighting their Black friends, some without even knowing it or trying.

In the book, he addresses the first time he blocked someone online because of a racial justice conversation.

After he posted about the killing of Freddie Gray, a 25-year-old Black man who in 2015 was arrested in Baltimore and died of a spinal cord injury while in police custody, a White friend he knew from church responded to his post by saying she had a tough experience as a White person while she was in another country.

“She tried to use her experience in another country to undermine what I was saying about Black people’s experience here,” he said, adding that he then realized that what she was really trying to do was not have a genuine good-faith conversation, but rather trying to shut down the conversation altogether.

“She was trying to basically say that it was not about skin color, it was not about race, so you should be quiet,” Henry said.

This is why he argues that it’s OK to end these relationships.

“At the end of the day, gaslighting, racial gaslighting, racism is a form of abuse. And no one is obligated to stay in an abusive relationship, even if the person who is participating in the abusive behavior doesn’t know what they’re doing,” he said.

“When we look at the situation of abuse, once you start taking responsibility for changing the abuser’s behavior, you’re now in a codependent unhealthy relationship. So Black people have to take care of ourselves. We can’t be preoccupied with trying to change every White person’s mind who wants to tell us that what we’re experiencing either is not real or we’re exaggerating it and all that kind of stuff,” he added.

In the book he also points out that it’s time for Black people to “rethink the fight for the proverbial seat at the table in White institutions. We need tables of our own.”

But that does not mean a form of separatism, he said.

Related Articles

This week’s bestsellers at Southern California’s independent bookstores

Discovering the hidden secrets of maps inspired ‘The Cartographers’ novelist Peng Shepherd

The Book Pages: How do you read these days?

‘Hollywood Medium’ Tyler Henry talks growing up, skeptics and memoir ‘Here & Hereafter’

This week’s bestsellers at Southern California’s independent bookstores

“When I say Black people should invest in our own institutions, it has to do with the fact that there are so many ways in which White people are unwilling to share power with us and we can’t continue to sit around and beg to be empowered. We have to empower ourselves,” he said.

Writing the book also forced Henry to reflect on his own actions, feelings and perspectives.

“Many of the things that I was trying to convey to the White friends I couldn’t keep were also lessons that I had to learn myself. Such as, I have a right to be angry about racial injustice, and it’s OK for me to be angry about racial injustice and to express that anger,” he said.

In the end, however, Henry says this book is about offering hope for a just society.

“What I’m hoping is that people will read this book and be fired up and hopeful about the potential for chance, for non-violent struggle,” he said.