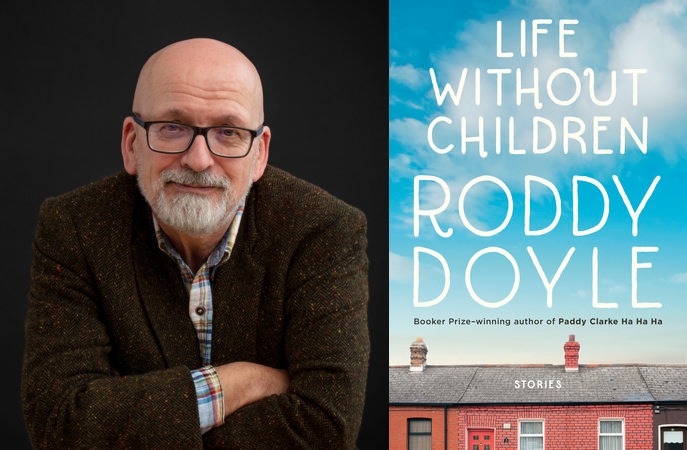

Roddy Doyle became a literary star with novels like “The Commitments,” “The Van,” and “Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha,” which teemed with exuberant life. But what do you write about when exuberance, and even life itself, has been sidelined? Doyle’s latest collection of short stories, “Life Without Children,” examines the quiet isolation and inner turmoil that seemed to blanket everything during the worst of the pandemic, even as we humans dealt with aging bodies, disappearing jobs and faltering marriages.

One character, in the title story, gets COVID-19 and is hospitalized but often it’s the way our world was disturbed and disrupted that knocks Doyle’s characters sideways. “Ripped from his life, he walks,” is the opening line of the story “Masks.” The nameless character is disgusted by the masks littering the footpath – and the people who toss them there – where so many seek solace when everything else is shut down, but he’s also busy berating himself. “His stride has its rhythm and it doesn’t vary – my fault, my fault, my fault, my fault. It doesn’t stop when he gets back to the house and sits, or when he lies down. The lockdown has ripped away the padding. There’s no schedule, or job, no commute. There’s nothing saving him.”

Fortunately, Doyle is a humanist at heart and most of the stories afford the characters some light, some humor, some hope, some grace to be found in their suffering. In a recent video interview about the collection, he even added that he is again looking to the future.

“I’ve started a novel which is set on the day the narrator gets her first vaccine jab,” he says. “I can imagine her moving on in life after that.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q. What made you start writing these stories?

I was in the U.K. when the lockdown started. When I got home and got the rhythm of distancing and we worked out a routine in the house, I went back to the novel I had started a few months before but realized it made no sense now and I couldn’t see myself making the character go into the lockdown.

I dumped it and began thinking about my experience in the U.K. – it was the first time I felt far, far away while there. Ireland was already in lockdown but the U.K. wasn’t and I went into the pharmacy and it was full of these old people hacking and coughing. I thought I could use that feeling and that’s where the story “Life Without Children” came from.

As I was writing that one, the story that became “Gone” – about a woman who uses the lockdown as an opportunity to walk out the door and disappear – came into my head. So I just thought I’d keep going.

Then masks were being introduced, which led to another idea, and then we could walk a bit further and then I was walking through these streets that were deserted in the middle of the day and I used those images in “The Five Lamps.” I was gathering up all these feelings and observations and that kept me going from March 2020 to March 2021

Q. That story is suffused with sadness and regret, yet it’s also filled with helping hands. It’s the last story in the book. Did you want us to remember how, during the pandemic, we could rely on the kindness of strangers?

Yes. It’s a small country – if you have 50 people die in a day, it’s a small amount but you don’t have to go too far to find out who one them is, you know. There were lots of stories during that time about people being kind and reaching out, leaving shopping outside doors. That notion of kindness resonated.

Q. Did the pandemic make us lonelier and more vulnerable, or did it just expose how lonely and vulnerable we already were?

The lockdown exposed an essential loneliness or aloneness that was already there, but there was also a new lurking fear of our mortality.

I certainly felt more alone, even though I’m used to being alone since I spend a lot of time working alone. I’m not a recluse – I love meeting friends, going to the local pub and having a slow pint. I love wandering around the city center, into the shop, into the café. I was missing friends and family, but I was missing the noise, too.

In the stories, I was imagining people who rely on the structures of their working day – their commute, the shopping at the supermarket – for their human contact and suddenly they weren’t getting it. That certainly made people feel more alone and vulnerable.

And mortality was rearing its ugly head everywhere. I’ve lost friends, family, my parents, so I’m used to death and grief, but as a psychological necessity we see death as a somewhat abstract thing, a philosophical concept we have to tackle at some point, but later on. Then the images we were seeing and the projections of how many people would die made us feel a genuine fear and vulnerability.

Q. The stories aren’t autobiographical, but how much of the anxiety and emotional turmoil came from your own life?

I wrote about my anxiety in “The Charger.” I remember going for a walk – we were only allowed to walk two kilometers early in the lockdown – and I got about halfway and realized my phone battery had gone. Normally, I couldn’t care less. But that day I couldn’t bring myself to walk any further, I was really anxious to get back home to charge the phone – I didn’t want to be out of contact with anybody in case something happened. It was a level of anxiety that really made concentration difficult.

Q. This is quieter than many of your earlier books. How much does that reflect the pandemic and how much is about getting older?

I live in a quiet house now because there are no children. The men in the stories are looking back, which is what we do when we get older because it’s so much more pleasant than looking forward, but also because you’ve no one to talk to, so you look back and remember.

When you’re writing quieter stories, you try to separate the honesty from the sentimentality – I enjoy looking at the little humiliations that occur as you grow older and I might as well use them.

But also the quiet during the lockdown was extraordinary. So many people were alone. You’d only hear a car go by every half hour as if it was the 1960s when you played football in the street. And in the early days fear of saying anything, of laughing, when there people in a coffin down the road.

People, including me, ended up with tinnitus because there was nothing there, including me. Apparently very quiet conditions can bring it on.

Q. Your men of a certain age struggle to communicate. That’s not just the pandemic.

Men of my generation are more limited. You have a job attached to you – this is most obvious in the blue-collar world – you’re a plumber or carpenter and that’s a big part of you. Women carry these other things better and talk more to each other. I admire younger men who are less defined by who they are, where they come from and what they’re supposed to be. They’ve invented themselves. But I’m stuck with what I have.