In recent days, the increasingly heated battle between Republicans hoping to advance out of the June primary and face Democratic Rep. Mike Levin in the November vote to represent the 49th Congressional District has largely focused on just three words.

Challenger Brian Maryott wanted his job title on the primary ballot to read “certified financial planner” after years of working in that field. But on March 21, fellow GOP candidate Lisa Bartlett filed a complaint about that, accusing Maryott of trying to mislead voters since he no longer works as a financial planner.

The Secretary of State’s office said in a statement that staff chatted with Maryott, and his campaign said Wednesday that after he’s learned about a trademark conflict with the use of the “certified” designation, he’s switching his job title to “businessman/nonprofit executive.”

From the outside, such distinctions might seem trivial. But the tussle between Maryott and Bartlett is just one of several fights over ballot titles that have popped up in California this election cycle. And the time and money spent over ballot job descriptions illustrates just how crucial candidates feel those few words can be.

“These three words are gold,” said Dan Schnur, politics professor at USC.

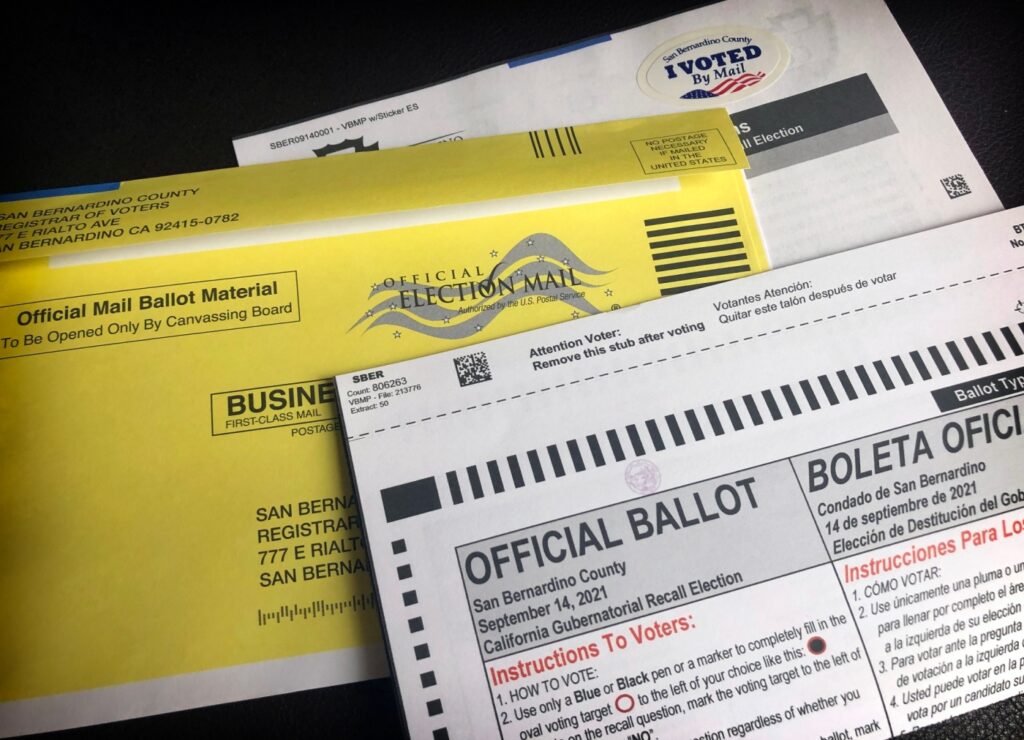

When Californians look at their June 7 primary ballot, they’ll see just three bits of information in state and federal races: the candidate’s name, his or her party affiliation, and their job title, which in state election law is known as “ballot designation.” For candidates in nonpartisan local contests, such as county supervisor and board of education races, the list shrinks to two: name and job title/ballot designation.

“This is the last message that voters will hear from a candidate before they cast their ballot,” Schnur said. And for low-information voters, who may do little to no outside research about candidates, Schnur said their decision could be based entirely on impressions they draw from those few words they see on the ballot.

Ballots are long and people are busy, noted Matt Reilly, a veteran Sacramento consultant who currently is working with several local Democratic candidates. So, while politicians like to believe that voters absorb every campaign ad and speech they make, and that voters then use that information when they make their choice, Reilly said consultants like him spend lots of time pouring over potential options for ballot designations.

The goal, he said, is to find three words (and no more than three) that are accurate and in line with state law, yet also send as many desired clues as possible to voters who are only learning about the candidate when they open up the ballot.

Under state election law, if the candidate is an incumbent or holds another elected office, they can state that title, which is generally considered a substantial advantage. Otherwise, the ballot designation must be a “description of no more than three words of your principal profession, vocation or occupation.”

The law then goes into great detail about what is and isn’t allowed, down to the punctuation. The designation, for example, must be the candidate’s “primary” work that requires substantial “time and effort.” It can’t be a hobby, occasional volunteer work, or a status such as “activist” or “patriot.”

Despite those details, candidates still have wiggle room to make statements that they hope will appeal to voters. When it comes to local congressional incumbents, for example, Linda Sánchez lists herself as “Mom/Congresswoman” while Mike Levin is “U.S. Representative 49th District.” (Ballot rules say office titles, and geographic locations, can go beyond the three-word limit.)

So while the question of “what’s your job?” seems like a simple one for most people to answer in three words or less, Reilly noted that candidates with lots of campaign money will sometimes poll voters to find out which options play best with their targeted demographic. Others rely on experienced consultants. And others simply have strong personal feelings about certain job titles, no matter what the data or experts might say.

The title of “business owner,” and particularly “small business owner,” is one of the most popular ballot designations, Schnur said. That’s particularly true of GOP candidates, though it cuts across party lines. And if they’re not a business owner, some variation of businessman/woman/person is the next best thing — even if it tells voters very little about what they actually do for a living.

Among 71 candidates vying in the primary for state and federal seats that touch Orange County, 32 of them mention “business” in their ballot designation. Twenty-five are Republicans and seven are Democrats.

Roughly a third of those 32 candidates refer to themselves as “business owners.” That includes CA-47 challenger Scott Baugh, who lists himself as “Orange County business owner,” rather than attorney, since he owns his own law firm.

The other two-thirds of those 32 candidates list themselves as “businessman,” “businesswoman” or “businessperson.” That includes Bartlett, who, along with being a county supervisor, has a real estate company and is involved in a startup that makes party cups that people can write on. And it now includes Maryott, who’s a former San Juan Capistrano council member.

When asked about the business and nonprofit referenced in his new ballot designation, Maryott’s campaign manager Megan House said he “is still an active investor” and he has started a nonprofit “that helps families in underserved communities with financial literacy and education” along with doing pro-bono consulting for other nonprofits. House didn’t respond to additional questions, including the name of Maryott’s nonprofit.

The only designation that Schnur said might rank higher than “business” titles is any sort of reference to military experience. But that one is tricky, Reilly noted, since candidates can’t use “veteran” and can’t list themselves as “ex-” or “former” anything. So, active members of the national guard, such as CA-45 Democratic challenger Jay Chen, can list their military service in their current job titles, while anyone who retired from fulltime service, such as CA-40 GOP challenger Greg Raths, can identify themselves as “retired” with their final rank.

Some professions score better depending on which political party they’re trying to woo, consultants said. “Police officer,” for example, is more effective with GOP voters, while “teacher” or “educator” increasingly plays better with Democratic voters.

In local county and city races, which are nonpartisan, Reilly said campaign teams sometimes use job descriptions to signal a candidate’s party affiliation even when they can’t say if they’re a Republican or Democrat.

The descriptions are regulated by the Secretary of State, though campaign consultants said it usually takes someone protesting a ballot title for those to kick in. And anyone can file a complaint or even a lawsuit over ballot designations.

One such battle played out in Sacramento County Superior Court on Wednesday afternoon.

Attorney General candidate Eric Early filed a petition asking a judge to stop his fellow GOP challenger, Nathan Hochman, from being listed on the primary ballot as “Attorney/General Counsel.” Not only are those not two separate jobs, Early’s complaint alleges, but he also argues that even with the slash between the titles the wording “misleads voters into quite possibly believing that he is presently the Attorney General.”

The judge agreed, Early said, giving Hochman the option in court between several alternatives. He went with “General Counsel.”

Hochman’s campaign didn’t immediately respond to requests for comment on the issue.

Whether a complaint has been filed or not, the Secretary of State can ask for more documentation to support a candidate’s requested ballot designation. Or the office can reject the request outright.

That’s what happened with Chris Mathys, a GOP challenger in Central California’s CA-22.

Mathys asked to be listed on the ballot as a “Trump Conservative.” The state said that’s a “status,” not a profession. Mathys filed a lawsuit but, KCET reported, the court ruled against him. So he’ll now be listed as a “Businessman/Rancher.”

In the wide open 38th State Senate District race, which overlaps with the House district that Maryott and Bartlett are hoping to represent, Encinitas Mayor Catherine Blakespear filed a complaint earlier this month over fellow Democratic challenger Joe Kerr using “retired fire captain” as his ballot designation, TheCoastNews.com reports. While Blakespear argued Kerr has had other jobs since he retired from a long career in firefighting a decade ago, Kerr’s campaign said the state allowed him to keep that designation.

Related Articles

Cypress city attorney defends closed-session vote against election districts

Why conservative Christians want to take over southwest Riverside County school boards

Cypress council casts closed-session vote to battle push for district elections

Congressional task force on human trafficking launches in Southern California

Effort to recall second Westminster council member falls flat

In the Orange County Board of Education race, incumbent Tim Shaw requested a ballot title of “Appointed Member” to the board. Someone filed a complaint amid controversy over how Shaw was re-appointed to his post after briefly quitting in 2021. But Shaw said the county Registrar informed him he was allowed to keep that designation.

With so much room for strategy and gamesmanship, the ballot rules in many other states let candidates list only their name and, for partisan races, party affiliation.

Lou Penrose, a veteran GOP consultant based in San Juan Capistrano, said that while ballot titles were “originally intended to assist the voter and provide some clarity into the candidate’s general background, the ballot designation challenge has far too often been used as merely a game of ‘gotcha’ by candidates and their campaigns, trying to score a negative headline on their opponents by arguing over semantics.”

That process, he added, “doesn’t lead to deeper voter engagement.”

But despite its flaws, Reilly said he thinks California law in this area is quite good as it stands.

“It polices, in a way, people from doing too much or misleading people. I think that’s the key responsibility of elections officials: keep things honest. And I think the law does that pretty well.”

Reporter Roxana Kopetman contributed to this story.